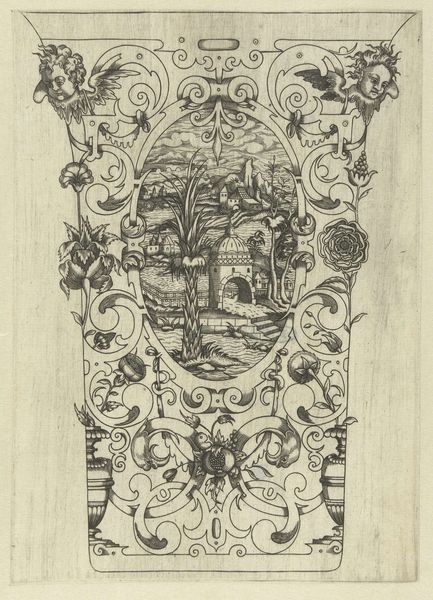

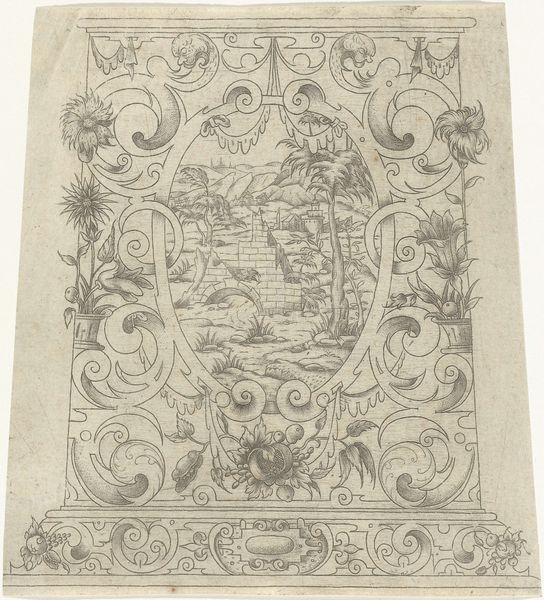

print, engraving

# print

#

old engraving style

#

landscape

#

11_renaissance

#

ink drawing experimentation

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 199 mm, width 134 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Right now, we're standing in front of a 17th-century engraving currently held at the Rijksmuseum. It's titled "Beker, met in het midden een ovaal met een landschap," which translates to "Beaker, with an oval containing a landscape in the middle.” Editor: My first thought is "exquisite," like an antique lace pattern captured in light and shadow. The fine detail—the way the landscape is nestled within all that swirling ornamentation—it feels so intimate. Curator: The image presents a detailed landscape scene contained within an ornate oval frame, meant to represent a beaker or goblet. These types of decorative prints were quite common. They weren’t necessarily designed to be displayed as artworks themselves. Instead, prints like this often served as design templates for artisans, goldsmiths or glassmakers who were looking for inspiration. Editor: So, imagine someone taking this image and meticulously etching it onto a delicate glass goblet. It's design-ception! You've got the landscape *within* the depicted beaker... So meta for the 1600s. I’m curious: Were these designs really used, and can we see evidence of similar patterns from that period on surviving objects? Curator: Yes, archaeological and museum collections contain abundant evidence of pattern-following in material culture and ornamental vocabulary. We see versions of such designs in ceramics, metalwork, even textiles across the Dutch Republic and beyond. What this print lacks in color, it more than makes up for in line work. Note the variety of patterns filling the negative space. Consider the social function too; by disseminating such prints, an entire class of artisans and eventually consumers became participants in a broader aesthetic discourse. Editor: Thinking of aesthetic discourses, even today, I can imagine endless takes on this design popping up in tattoos. Speaking personally, I find the two cherubs peeking out on the top add a certain cheekiness to the composition. It feels like they're in on some joke, looking down at the serious landscape below. A fun juxtaposition of the sacred and the ornamental. Curator: True enough, and seeing it through your perspective is a welcome breath of fresh air in evaluating early modern imagery. Editor: Well, I am glad to provide. Art really invites you to linger in your imagination if you grant it time and patience. Thanks for all the history!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.