Dimensions: height 195 mm, width 215 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

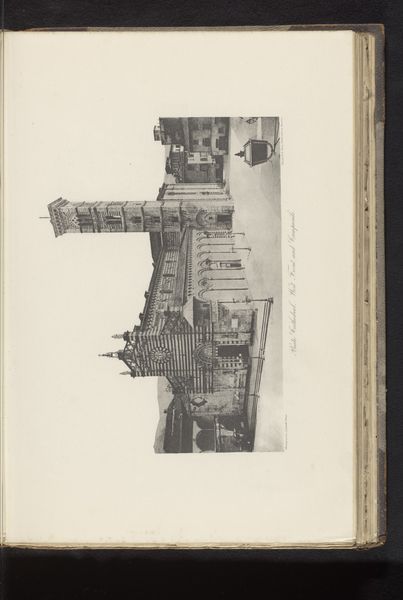

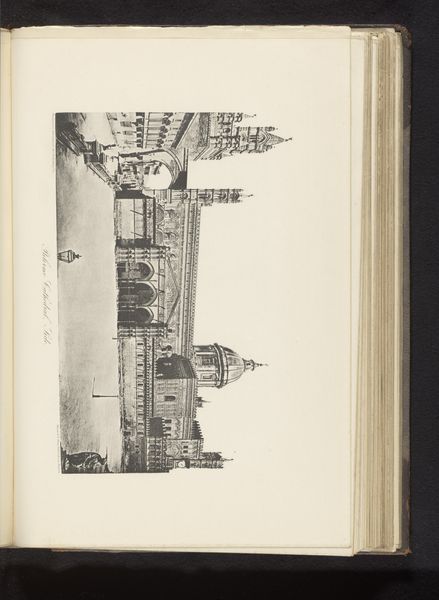

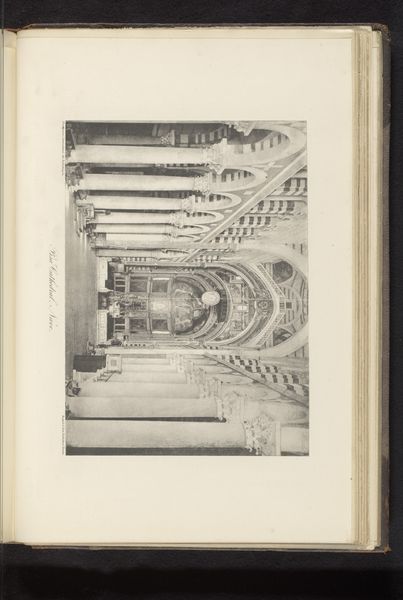

Editor: Here we have an ink and engraving print entitled “Gezicht op de Basiliek van San Marco te Venetië,” or “View of the Basilica of San Marco in Venice,” created sometime before 1886. The meticulous detail is impressive. What can you tell me about this cityscape? Curator: Well, Venice wasn’t simply a beautiful city, but a major center of power and commerce. Prints like this weren't just picturesque souvenirs. How might images of Venice function within broader sociopolitical contexts of the late 19th century, especially considering Venice's declining power? Editor: So, not just about aesthetics? Maybe these prints acted as reminders of Venice's past glory, circulating ideas about national identity and cultural heritage, as a means of tourism. Curator: Exactly. Now, consider who had access to such imagery. Think about the rising middle class, eager to consume culture, who could then partake in this collective imagining. How might this accessibility challenge traditional notions of who gets to participate in shaping cultural narratives? Editor: It democratizes the image, making it less about the elite and more about a shared cultural experience. It allows more individuals to feel connected to a place. The very act of recreating and distributing it reinforces this new shared vision. Curator: Precisely. So, what we initially perceive as a simple landscape becomes deeply entangled with identity politics, economic shifts, and representational power. Are there ways you see that connecting to today? Editor: For sure. Even now, we consume and circulate images, especially online, helping form how we view locations and different cultural heritages, and by doing so reinforce certain viewpoints or change collective understandings. Curator: Right! Understanding that socio-political function empowers us to engage with art in a more critical and informed way.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.