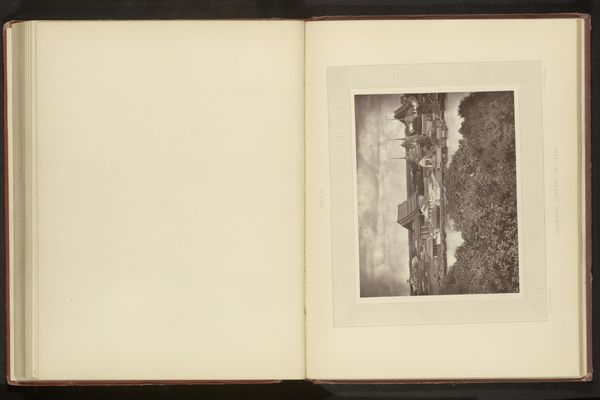

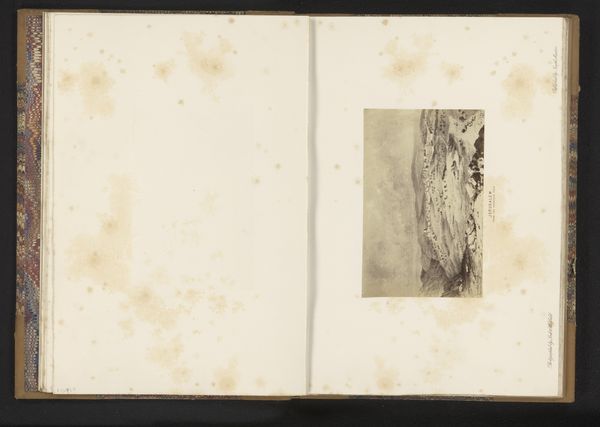

Jerusalem-The village of Siloam in the Valley of Jehosophat with the Hill of Evil Counsel and the Valley of Hinnom before 1866

0:00

0:00

#

type repetition

#

homemade paper

#

typeface

#

personal sketchbook

#

hand-drawn typeface

#

fading type

#

stylized text

#

thick font

#

delicate typography

#

columned text

Dimensions: height 97 mm, width 128 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Let’s spend a moment with this striking image by Francis Bedford, created before 1866. It's titled "Jerusalem-The village of Siloam in the Valley of Jehosophat with the Hill of Evil Counsel and the Valley of Hinnom". We’re seeing a page from what seems to be Bedford's personal sketchbook. Editor: It feels surprisingly intimate, doesn't it? A little, almost lost world held within those pages. The monochrome adds a weightiness to the landscape, a gravity that speaks to history and perhaps conflict, or more accurately the human drama which constantly repeats itself throughout it. Curator: Bedford was one of the most prominent photographers of his day, known for his topographical views, particularly those taken during his travels to the Middle East in the 1860s. Queen Victoria commissioned him. So you see, he has a foot both in high society and is deeply involved with visual documentation. It appears that Bedford was as engaged with empire, royalty, religion and conquest, as with the people who happened to be involved with his project. Editor: Absolutely. I think knowing it was part of a commission brings a different lens to view the subject matter with; it becomes clear how the image fits into a broader, politically charged narrative. We should talk about how he positions the village and its people here, like a specimen. Does he afford any agency to the place or the local people, or is it all subservient to some Victorian vision of the 'holy land'. Curator: The composition is meticulously arranged; Bedford highlights key sites like the village of Siloam. What strikes me is the relationship between these markers of religion and places, and the power associated to them. What purpose do the personal musings at the edge of the composition serve, and for who? Editor: Those hand-drawn texts give an important element. Their 'authenticity', versus that of the printed photograph in this context can lead to some fascinating questions regarding ownership, not least how and if they represent the sitter; who owns the truth and authority in their joint vision? Curator: Yes. As it sits within a sketchbook, do you believe that those notations act like a personal authentication by the hand of the artist? Perhaps a reminder of place or the narrative that ties the work into a location beyond this book, maybe? Editor: I'd lean towards yes. It's a space for thought and further reflection, to create layers that enhance the conversation around that singular photograph and a world it invites one into. Ultimately, the piece makes me consider that photography, much like the written word can both obscure as much as it reveals.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.