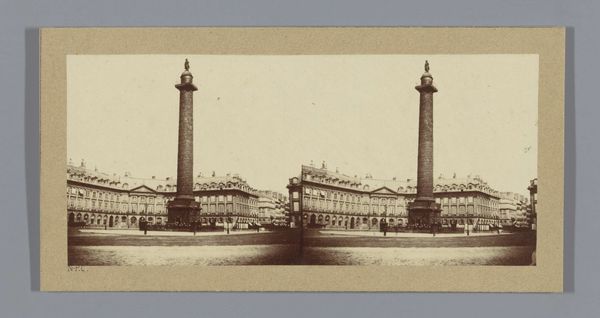

photography

#

photography

#

cityscape

#

realism

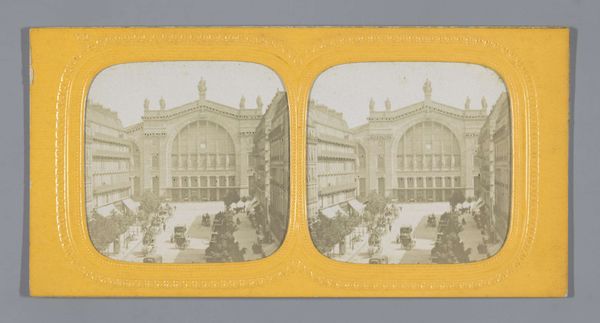

Dimensions: height 85 mm, width 176 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

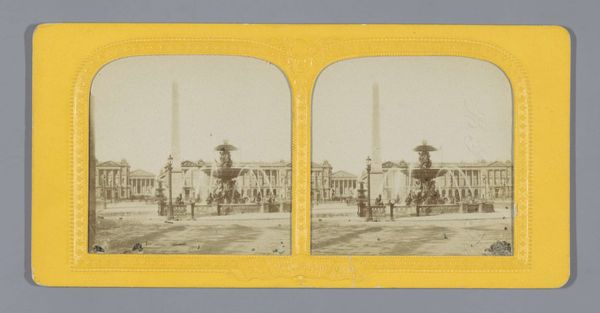

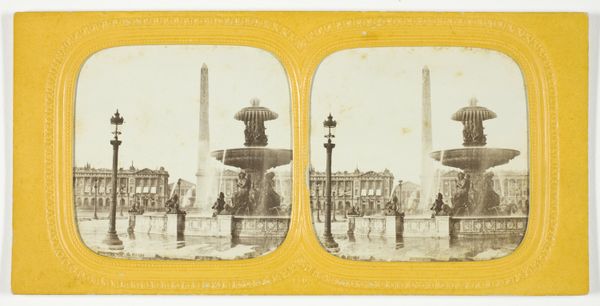

Editor: This stereoscopic photograph captures the Place de la Concorde in Paris, sometime between 1855 and 1865. I'm struck by the muted tones and how the photo gives this iconic place a somewhat deserted, almost ghostly feeling. What are your thoughts when you look at this, especially considering the context of photographic practices at the time? Curator: It’s fascinating to consider this image through a materialist lens, thinking about the labor involved in its creation. Photography in the mid-19th century was a laborious process. This image, reproduced as a stereograph, speaks to a burgeoning culture of mass production and visual consumption. Editor: Mass production of photographs – that’s not something I'd immediately connect to such an old image! Could you elaborate on the material conditions that enabled this? Curator: Certainly. Think about the chemicals required – silver nitrate, developing agents. Then there's the glass plate negative, the printing process, and the card stock. All these materials needed to be sourced, manufactured, and distributed. This wasn’t just art; it was industry. And consider who had access to these images and how these early photographic technologies might affect class structures and tourism, and access to experiences that were once only available to wealthy. What kind of narratives and experiences were mass-produced and circulated? Editor: So, the aesthetic of this piece isn't just about artistic intent but is intrinsically linked to industrial capabilities? It makes you think about the role the workforce would play in creating those photographic materials. Curator: Precisely. The ‘realism’ style that's been identified speaks not just to a choice, but perhaps also to a particular social agenda related to these changes. The photograph is as much a product of material conditions and technological advancements as it is an artistic statement. And thinking about photography as a material object that enters a market complicates our understandings of value and aesthetic experience. Editor: This really changes how I see the image; it’s less a captured moment and more a layered object shaped by manufacturing and labor. I appreciate that. Curator: Indeed. Seeing art through a materialist perspective invites us to interrogate not just what the image represents but also how it came to be and the societal forces that shaped its production and distribution.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.