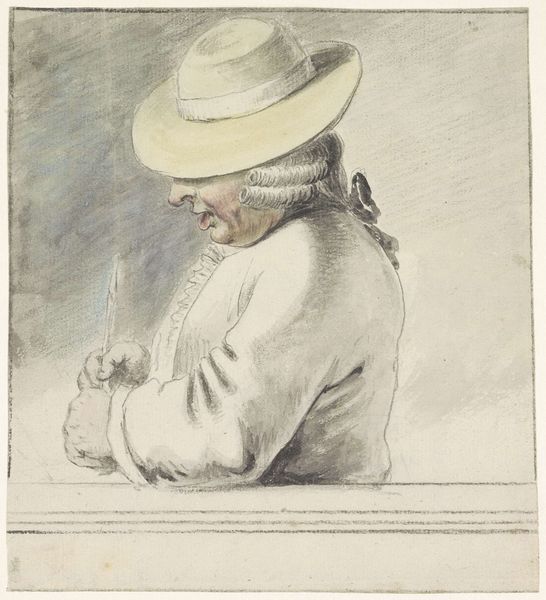

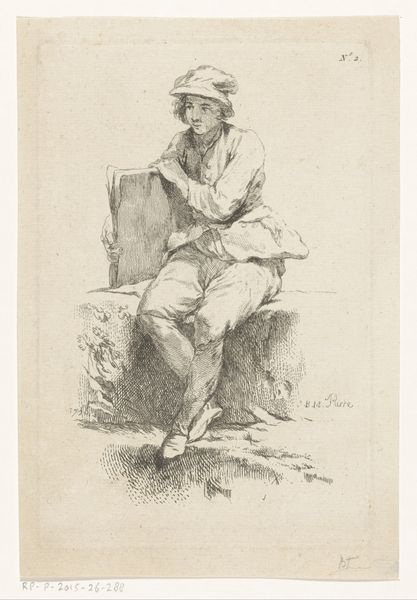

Portret van Johann Goll van Franckenstein, met hoed, naar links Possibly 1783

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: height 160 mm, width 134 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Let’s consider this drawing, thought to have been created around 1783 by Louis Bernard Coclers. It is entitled "Portret van Johann Goll van Franckenstein, met hoed, naar links," depicting a man, presumably Johann Goll von Franckenstein, in a somewhat informal portrait. The media includes charcoal and watercolor. What’s your initial impression? Editor: Well, he appears completely absorbed. The hat casting a shadow, concealing his eyes... It creates a feeling of introspective privacy. There's a seriousness despite the Rococo flourishes in his wig and clothing. It almost feels as though we're intruding on a private moment of deep thought. Curator: It's fascinating how Coclers captures a sense of the subject's personality, even with the averted gaze. To situate it further, the late 18th century was a period of significant social and political upheaval. Think about it in context; we are looking at the enlightenment period. The man might represent something of class inequality if we look closer. What's your read of this? Editor: I am not too certain; let's consider a contrasting perspective; I would instead consider that his gesture, hand bent in study, quill at work, represents perhaps an administrator, a scholar or accountant-- and perhaps an intentional demonstration of self-fashioning. Curator: Fascinating. It also presents an interesting juxtaposition of personal and public identity through his portrayal. While the composition places the subject in deep focus, there's this clear statement of power in the details, like the refined coat and expertly crafted wig, even in such simple materials as watercolor and charcoal. It might be seen to evoke ideas surrounding identity and social change. Editor: Yes, indeed. He may want to appear the way the hat is presenting him: as the face of a merchant or diplomat, his gaze obscured, his intentions private but certainly weighty and impactful in commerce. Curator: By situating it in such narratives, we can begin to address representation in this period, asking not just who is in the portrait but also what structures of power enable its existence. Editor: Reflecting on this further, this is one such demonstration of visual memory, a potent reminder that art, even in what appear to be simple forms like this portrait, often encode complex ideas, narratives, and cultural ideals about self and the world.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.