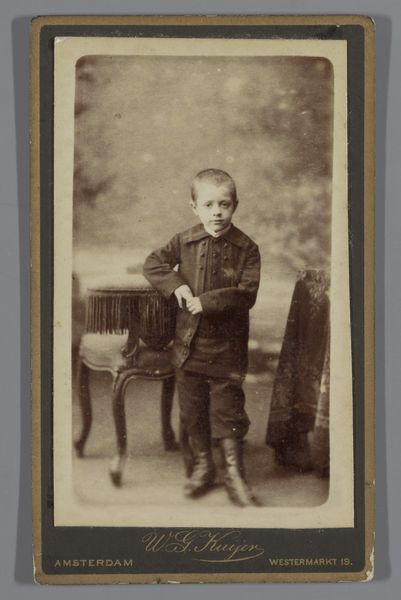

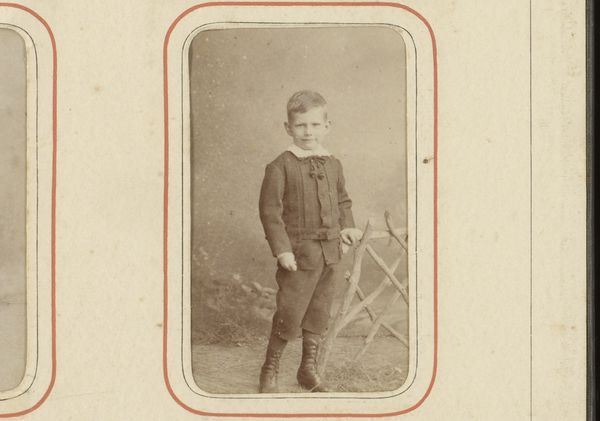

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

realism

Dimensions: height 135 mm, width 96 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

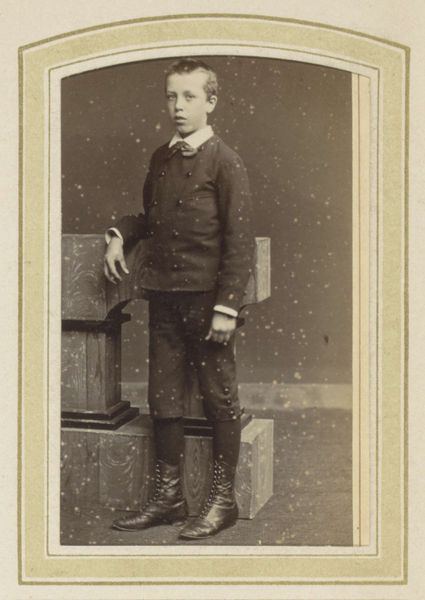

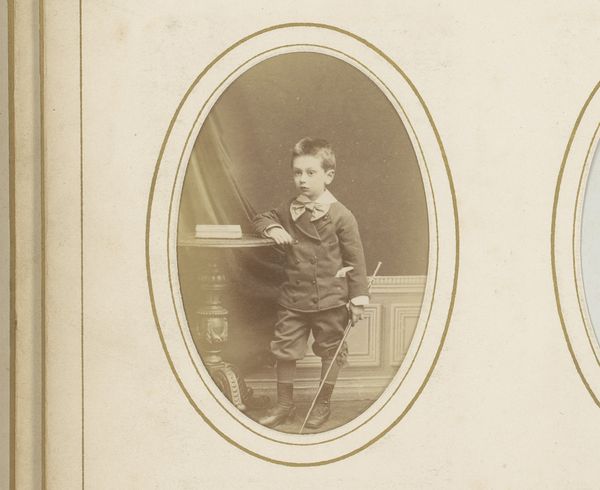

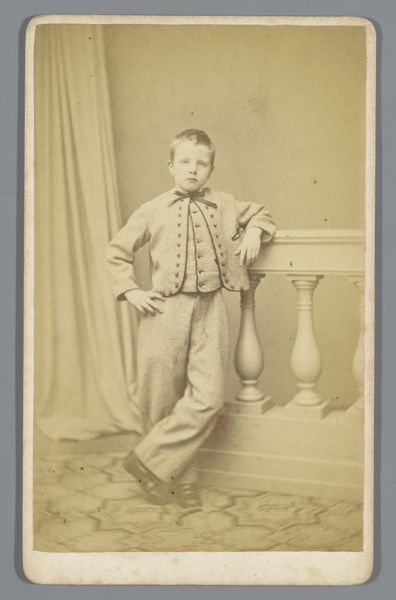

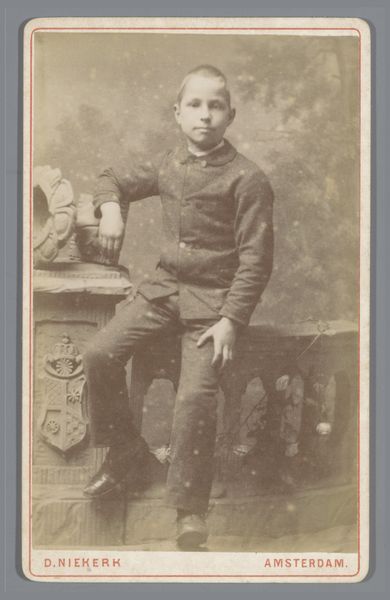

Curator: The gelatin-silver print you're looking at, titled "Portret van een jongen, staand op een stoel," roughly translates to "Portrait of a boy, standing on a chair," and dates from 1860 to 1900. What are your immediate thoughts? Editor: There’s a world-weariness about this little guy, right? The perfectly tailored suit, the assertive hand on the hip, but that gaze—it's seen something, or maybe it just misses playtime. He looks like he's about to give a very important lecture on stock options, even though he's on a little chair! Curator: His attire does tell a story. The formality points to the rise of bourgeois culture and portraiture’s role in constructing and signaling social identity during this period. These commissioned photographs acted as a type of social currency. Editor: Right, so this wasn't just about freezing a moment, but projecting an image—literally. Did these young lads even get a say in how they were presented? I wonder if he ripped off that stiff collar the second the photographer packed up. Imagine the stories behind those serious little faces. Curator: Undoubtedly. The act of commissioning such a photograph speaks to societal expectations around gender and class. The boy's carefully constructed image becomes part of a visual narrative defining his position. He represents the ideal of boyhood in that era: composed, respectable, and carrying the weight of future responsibility. Editor: Heavy is the head that wears the perfectly combed hair, I suppose! It does spark so many questions about childhood then versus now—about agency, expression. And who decided that standing on fancy furniture was the epitome of portraiture elegance? The composition seems hilarious in a way. Curator: Humorous perhaps, but also deliberate. Consider the symbolism: the chair elevates him, quite literally, suggesting upward mobility and social status. Even his expression can be considered part of this performance. We might read the performance now through modern considerations of power dynamics, class, and even performativity, if we think about Judith Butler, for example. Editor: Yes, yes! See, art history can be so powerful when related to what’s current. The context—who took the image, for whom, and the image itself becomes so enriched. You start peeling away the layers like an onion. He almost feels like an antique meme in a way! What would the comments section have been back then? Curator: Precisely. It’s this weaving together of historical context, material conditions, and social performance that breathes life into the image and allows it to speak across time. The image stops being static and enters a broader cultural dialogue. Editor: Agreed. Well, I know what *I* got out of that portrait and the discussion! This image really sparks one to challenge everything it throws out there and to think about its context, with modern life in mind. Curator: Indeed! An artwork truly gains relevance and resonance when we look through the critical lenses and weave its many intersectional threads through time.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.