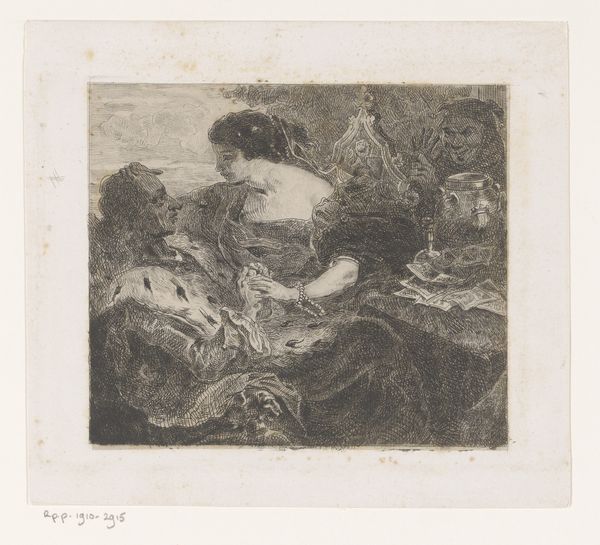

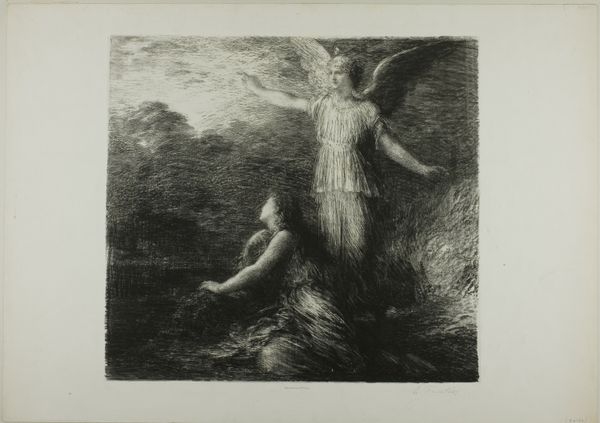

Dimensions: 305 × 394 mm (image); 488 × 641 mm (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Henri Fantin-Latour’s “Manfred and Astartea, third plate,” created in 1892, is a compelling lithograph. It's currently held here at The Art Institute of Chicago. What are your initial thoughts on encountering this work? Editor: A sense of melancholic longing. The contrast between the luminous figure and the dark, cloaked man evokes themes of unattainable beauty and perhaps forbidden desire. There’s something deeply Romantic here. Curator: Absolutely. Fantin-Latour was fascinated by Romantic literature and music, and here he translates Lord Byron's poem "Manfred" into visual form. The print itself is a lithograph, allowing for incredibly subtle tonal gradations. Notice how the artist uses the greasy crayon on the stone to achieve a sense of ethereal light emanating from Astartea. It invites reflections on craft and skilled application to the creation of art, in comparison to paintings. Editor: It’s interesting how Astartea is presented as this idealized, almost spectral, nude figure. Within a feminist context, it raises questions about the male gaze and the representation of women as objects of male fantasy or salvation. What commentary, if any, is being made on these power dynamics in relation to the poem and larger society? Curator: That is a critical entry point. Consider also the materials themselves: paper, ink, and the lithographic stone, and how those resources historically were mobilized, considering that paper was at the time more and more being sourced industrially through new chemical means with all its industrial waste, whereas the artwork idealizes Romantic retreat into an untainted natural realm. Editor: Thinking about historical context again, late 19th-century France was also deeply entangled in colonialism, which impacted societal constructions of beauty and the "other." What role might race and power have played in shaping the way that both Manfred and Astartea were conceived? Fantin-Latour and others like him who also pursued exotic themes. Curator: That brings in a richer dialogue with its complex artistic, industrial, and societal forces, a reminder that even apparently solitary artists are operating with materials and practices thoroughly grounded in broader power structures. And to push a little further here, can we connect this print in any way to current digital reproductions, where images circulate almost freely but underlying material structures and production still impose on their distribution and cultural power? Editor: That question underscores how deeply intertwined these artistic and material practices are within socioeconomic forces, as we see in Fantin-Latour's romanticism that might romanticize fleeing that societal landscape, though the works he produces are deeply part of that very landscape. Thank you, this has been incredibly insightful. Curator: Likewise. Looking at the historical processes can bring artworks to the contemporary foreground for critical examination, with important lessons about social change that extend even today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.