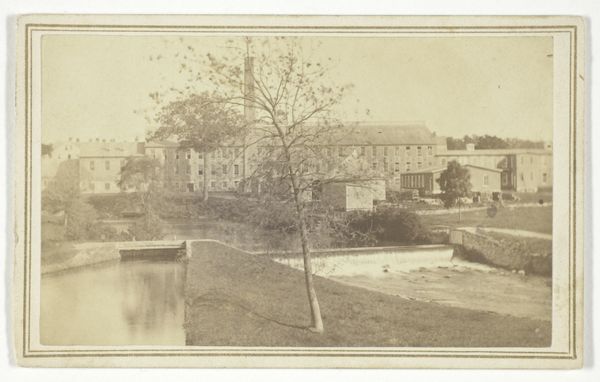

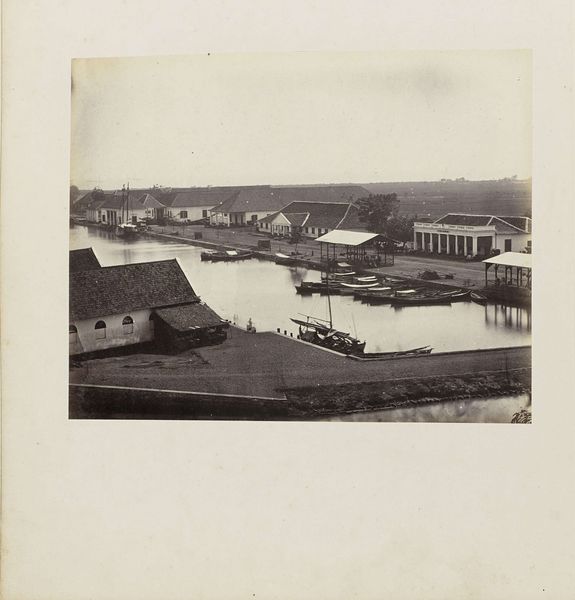

Gezicht op de Muiderpoort en de garancinefabriek in Amsterdam 1852 - 1860

0:00

0:00

eduardisaacasser

Rijksmuseum

Dimensions: height 123 mm, width 154 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This intriguing albumen print captures a view of the Muiderpoort and garancine factory in Amsterdam. The piece, by Eduard Isaac Asser, dates roughly from 1852 to 1860. What are your initial thoughts on this cityscape, given its blended romantic and realist style? Editor: It’s… unexpectedly haunting. The monochrome tones give it a melancholic feel, and the juxtaposition of the classical architecture with the stark industrial chimney is striking. There’s almost a dystopian air, considering when it was made. What were the political implications of recording urban development? Curator: It's crucial to remember that Asser lived and worked within a rapidly changing Amsterdam, one wrestling with industrialization and its consequences. Photography at the time was far from objective; consider how Asser positions the classical gate – the Muiderpoort – alongside the garancine factory. Garancine, a dye extracted from the madder root, was vital to the textile industry and also a potential carcinogen. Editor: Yes, that juxtaposition speaks volumes. The factory chimney feels almost like an encroachment, a visual symbol of progress threatening established aesthetic and social values. Were people critical of this early urban photography? Did they see it as an embrace of progress or an indictment of industrialization’s impact? Curator: It's a complicated picture. Early photography was often viewed as a scientific tool, documenting changes without inherent critique. But the choice of subject matter, framing, and even the printing process, could convey a particular stance. By framing this factory and gate together, Asser compels us to question what progress looks like and for whom. What were the labor conditions at this factory, for instance? Who lived near the Muiderpoort and what were their concerns? Editor: That brings us to the key question of representation and power. The photographic lens wasn’t neutral; it reflected and amplified the values of the person behind it and of the culture industry. Exploring these intersections of progress, labor, class, and visual culture seems essential for a better interpretation of this photograph. I have gained so much perspective after our conversation, thank you. Curator: It is indeed, especially today. By recognizing that a work of art can simultaneously reflect progress and mask exploitation, we approach a much more ethical understanding. Thank you.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.