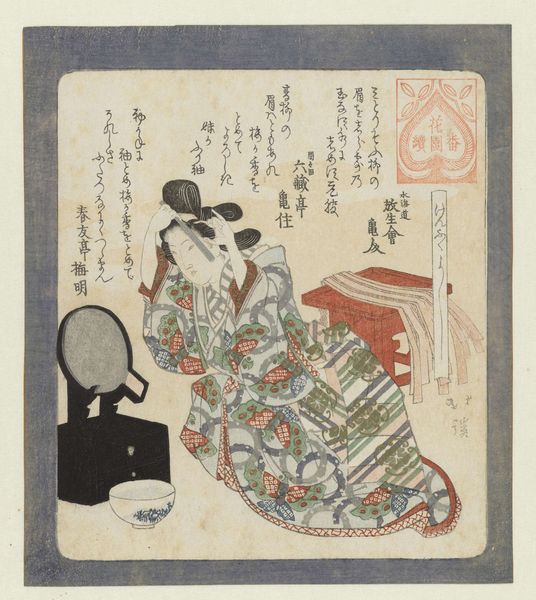

The Doll Festival, Third Day of the Third Month 19th century

0:00

0:00

print, paper, ink, woodblock-print

#

portrait

#

narrative-art

# print

#

book

#

asian-art

#

ukiyo-e

#

figuration

#

paper

#

ink

#

woodblock-print

Dimensions: 8 1/4 x 7 3/8 in. (21 x 18.7 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

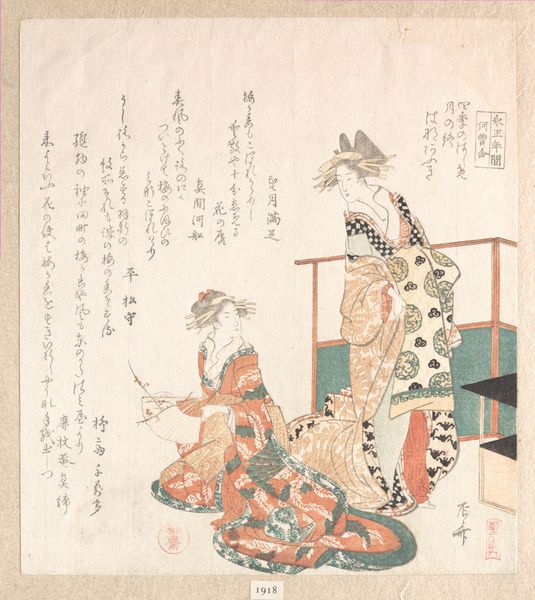

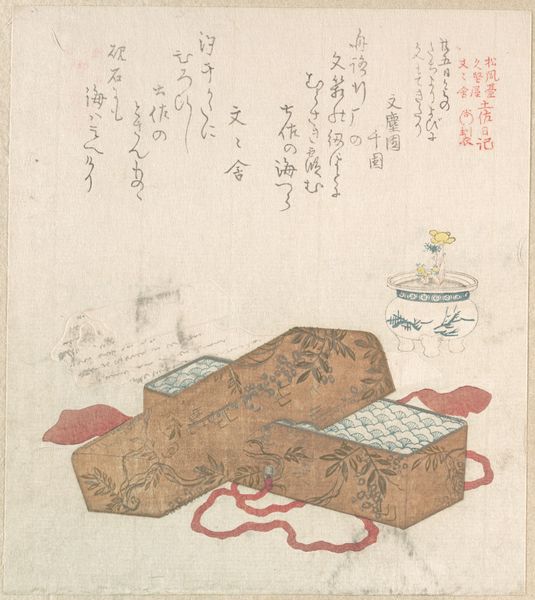

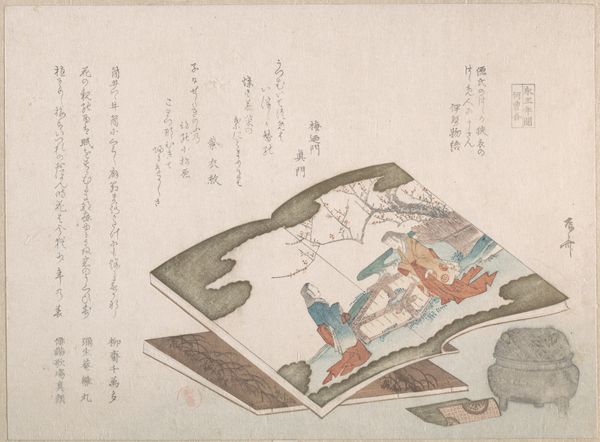

Curator: Let’s turn our attention to this vibrant woodblock print, “The Doll Festival, Third Day of the Third Month,” created in 19th-century Japan by Kubo Shunman. It's currently held in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: My immediate reaction is of a carefully arranged still life. The colors are muted yet rich, and there's a stillness that invites closer inspection. What particularly grabs me is the texture of those lacquered stands and how it contrasts with the doll’s smooth finish. Curator: Absolutely. This image gives us a peek into the 'Girl's Day' celebrations, a very specific cultural moment focused on well-being. These festivals and the imagery that accompanies them were carefully constructed displays of status and cultural identity. Editor: I’m especially curious about the materials employed, and the labor behind the printmaking. You can see the clear impression of the wood grain; the registration, whilst refined, isn't perfect - these small imperfections that signal human interaction. What can we discern about print production? Curator: The print, as a medium, became incredibly significant during this period in Japan. It facilitated wider dissemination of cultural norms and values among different social classes, not just the elite. The Doll Festival itself, while traditionally aristocratic, was being adopted by merchant classes. Editor: Exactly, the democratization of art production and ownership, particularly within urban centres, shifted cultural priorities. The Ukiyo-e tradition valued accessible artistic expression which in turn reflects material availability as much as cultural desires. Curator: Considering its display within the context of museums and galleries now, there’s a sense of transporting these ritual objects, and their history, into our own cultural understanding. How do we, as viewers in a different era, engage with such symbolism? Editor: The journey of this object from private ritual space to the public museum allows reflection on shifting tastes. While initially serving as culturally embedded tools, the material object becomes open to reassessment under present market values and ethical viewing contexts. It certainly asks questions about whose traditions are elevated in the West, and how these are materially made. Curator: I think it prompts consideration of how we assign value, culturally and materially, to objects from other eras, particularly in a museum context. Editor: I agree. It really shows us the multi-layered readings we can draw when art shifts in function over the centuries, especially when focusing on both process and sociopolitical context.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.