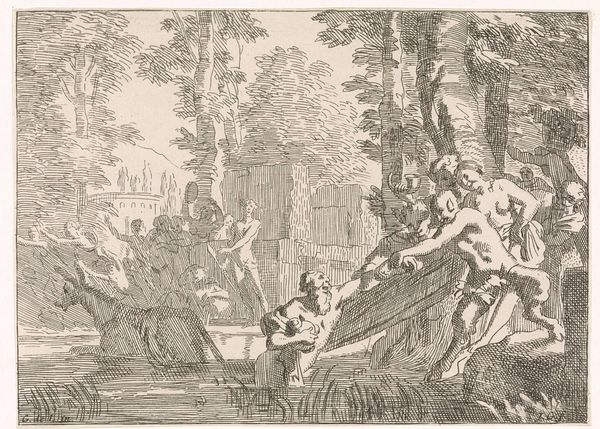

Allegorische voorstelling met kinderen en attributen van de Landbouw 1740s

0:00

0:00

drawing, pencil

#

drawing

#

allegory

#

pencil sketch

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

pencil

#

genre-painting

#

rococo

Dimensions: height 163 mm, width 194 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have Johann Heinrich Keller's "Allegorical Representation with Children and Attributes of Agriculture" from the 1740s. Editor: It's charming, almost excessively so. The children are so round and smooth, evoking this Rococo vision of a pre-industrial idyll. There is a light-heartedness despite it all, like farm work is actually adorable, rather than laborious. Curator: Exactly! The pencil work is delicate, creating soft, almost blurred edges. Notice how Keller uses the pencil to build up depth in the landscape, creating subtle shifts in tone. You get a real sense of the textures too—the roughness of the harvested grain, the smoothness of the children’s skin, even the grain of the wooden chest at the bottom. This level of materiality really gives the Rococo era an entry into working conditions and production, which many overlook because of its emphasis on "frivolity." Editor: Absolutely. Considering the era, there’s a strong undercurrent of idealization. We have cherubic children standing in for farmhands which really washes over any actual insight into agricultural labor. In whose imagination is agrarian toil child's play? The use of children naturalizes exploitation, cloaking social hierarchies within the visual language of pastoral scenes and childish fun. The title labels this artwork "Allegorical," it asks its audience to unpack all its layers rather than take its representations at face value. Curator: I see what you mean about exploitation! Thinking about it through an allegorical lens definitely sheds some light. Editor: And it isn’t simply the figures that are idealized. There is grain stacked on top of a large chest as pumpkins surround it. All these allude to the season's production value and abundance. It has all the markers of a "good harvest" if one did not know any better. This could easily be seen as propaganda due to the realities it willingly excludes. Curator: Precisely. Keller shows us the fruit, not the roots – or the dirt. Thinking about art patronage back then, who would commission this type of idyllic image and why? Editor: People always romanticize agrarian societies, which further helps this artwork’s narrative. Perhaps these commissioned pieces placated a ruling class so as to assure them their riches were secure from those out in the fields and growing? That this wealth will continue to exist so long as children happily run around said fields, playfully and willingly? Curator: Right. Shifting perspective on how idyllic production practices, the tools used to create such pieces, and who commissioned the artworks themselves are helpful to explore. Editor: Absolutely. This gives us much to reconsider in seemingly idyllic works.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.