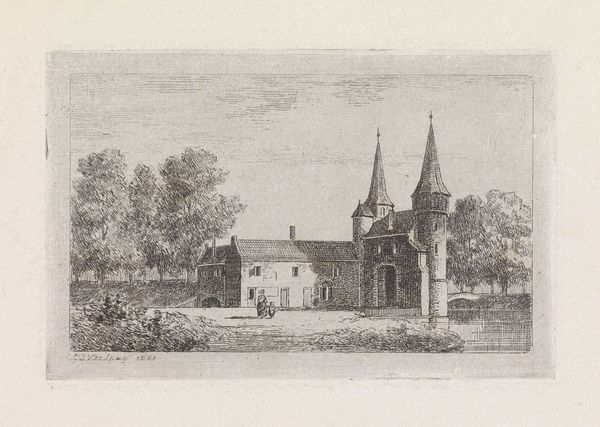

print, engraving

# print

#

landscape

#

cityscape

#

history-painting

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 198 mm, width 225 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

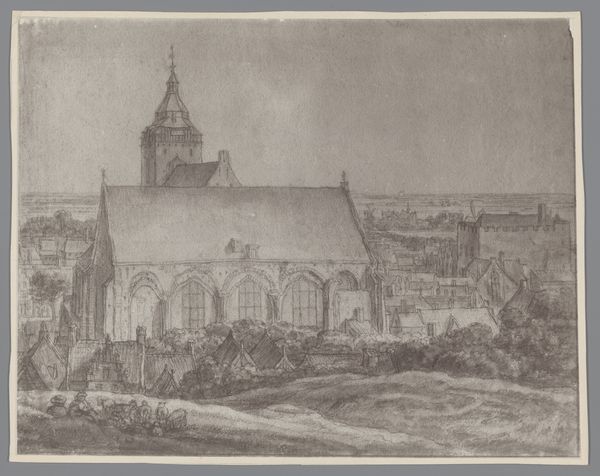

Curator: Looking at this, I'm struck by the echoes of history...It feels both solid and spectral, doesn't it? Editor: It certainly does. We’re looking at “View of the Former Abbey of Echternach” by Isaac Weissenbruch, created in 1873. It’s an engraving, a print capturing the Abbey in Luxembourg. I can’t help but be drawn to the labor and the reproduction facilitated by this technique. Curator: Labor, yes, but I see more a ghostly reflection. That Abbey, that imposing structure—it carries centuries within its stones. Do you feel the weight? It’s like a memory etched in monochrome. Editor: The material weight of all those stones is not insignificant. This technique democratized images— suddenly, cityscapes and historical buildings become reproducible, marketable. Consider the socio-economic implications of this accessibility! Curator: Marketable…you speak of commerce; I dream of souls! Though, perhaps they are intertwined here. The print medium has a kind of stark directness. It invites contemplation, as Weissenbruch gives you everything in simple black and white. Editor: It's a commodity, reproduced on paper, touched by so many hands! Each print is an iteration, connected to the other through the means of production, through paper and ink and process. What sort of papers were used at the time? Curator: All that talk of practicality obscures its power. What if we imagined the artist feeling connected to the divine somehow through his work on this holy structure? Or seeing the abbey's decline—observing how faith shifted or faded through the years, recording it into an easily reproducible format, perhaps that’s why he engraved the image. Editor: Maybe that same technology allowed for copies of communist manifestos or images that would instigate societal revolutions. The materials and methods used hold so much importance for disseminating so many ideologies, that would ultimately change even something as eternal as a holy structure such as this abbey. Curator: It's like a map. Weissenbruch provides more than what his etching depicts; he unlocks doorways, which lead us to echoes of shared cultural meaning across a particular place and time. What do you think? Is there more we could see beyond the materials at hand? Editor: There’s a clear intersection of method and concept and societal context in the way it renders and reproduces meaning, that continues to exist in all processes of artistic production. I feel ready to study some related works to fully grasp these implications, don’t you?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.