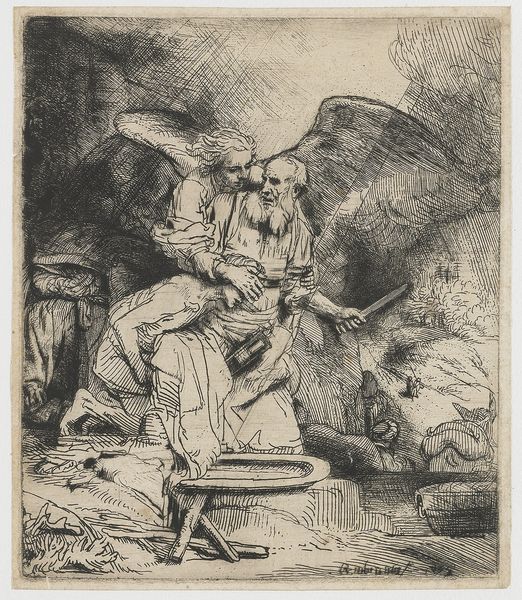

drawing, print, etching

#

drawing

#

baroque

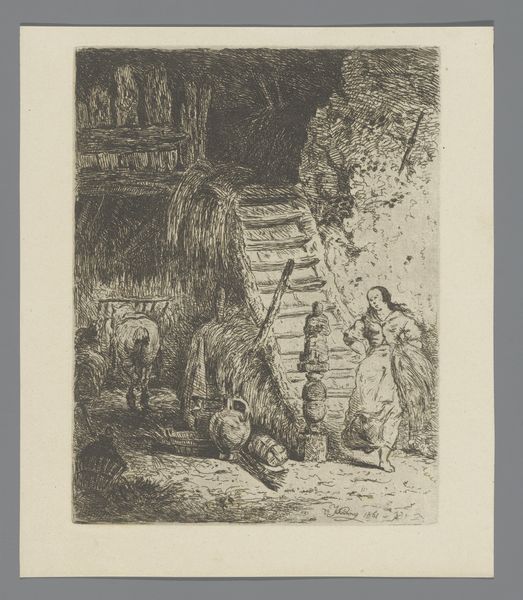

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

figuration

Dimensions: Sheet (Trimmed): 4 3/8 × 3 9/16 in. (11.1 × 9 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This is Rembrandt van Rijn’s etching, “The Agony in the Garden,” created sometime between 1647 and 1657. Editor: There's a stark contrast here. The heavy lines etched into the plate create an oppressive atmosphere, mirroring the scene's emotional weight. It looks as though all hope is lost. Curator: It’s remarkable how Rembrandt uses the etching process to build such deep tonal contrasts, isn't it? Think of the technical skill required, manipulating the copper plate, controlling the acid’s bite to achieve such luminosity in places and profound darkness in others. You can almost feel the work that has gone into it. Editor: Absolutely. The religious theme positions the individual—Christ—against institutional power embodied by the looming, dark structures in the background. Rembrandt's placement underscores the tension between personal sacrifice and broader socio-political systems of the period. It's a narrative etched—literally and figuratively—in suffering. Curator: I'm fascinated by the relationship between drawing and printing inherent in the etching process. It allows Rembrandt to explore line and tone in a manner that a straightforward drawing would not. This particular print allows us to think about art production during a specific period in the Netherlands. The market demand would inevitably dictate the number of copies produced, and the wear of the plate, its subsequent states, provide material evidence of its journey of consumption. Editor: Right, and it speaks volumes about faith during periods of great upheaval. Religious narratives offer a space to discuss social injustices, political angst, and the individual's place in the grand scheme. This agony, represented with striking human vulnerability, becomes universalized through the print’s accessibility and mass circulation. How does this work then connect with current socio-political discourse today? Does the piece lose potency with its traditional approach, or does this enhance our engagement with it? Curator: It offers such tangible insights into the economics of artmaking and consumption, revealing production practices during the Dutch Golden Age. Editor: The print becomes both a mirror reflecting historical realities and a window into ongoing struggles, rendering it remarkably relevant. Curator: A wonderful intersection of the artistic and the societal, don't you think? Editor: It's in these nuanced connections where its continued resonance truly lies.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.