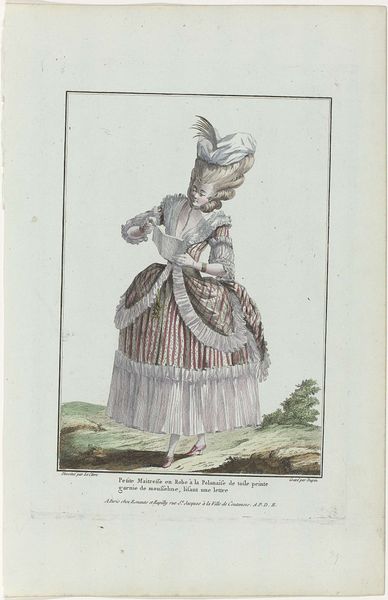

Gallerie des Modes et Costumes Français, 1785, nr. 3, nr.6, Kopie naar L 64 : Jolie Femme en deshabillé (...) c. 1785

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: height 179 mm, width 111 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: We're looking at "Gallerie des Modes et Costumes Français, 1785, nr. 3, nr.6, Kopie naar L 64 : Jolie Femme en deshabillé (...)", created around 1785 by Pierre Gleich. It's a print, specifically an engraving. Editor: My first impression is definitely Rococo extravagance. The sheer height of that hairstyle! And the way the fabric drapes... it feels almost playfully absurd. Curator: The print perfectly encapsulates the visual culture of the late 18th century. These fashion plates served as aspirational tools for women, showcasing the latest styles and ideals of beauty, and, implicitly, class. This era saw massive social inequality right before the French Revolution, and the hyper-stylized dress here speaks to the excessive consumption. Editor: Absolutely. I immediately focus on the labor implied by this image. Who is making this incredibly complex dress, this elaborate wig? The production clearly involves a whole network of skilled artisans, dressmakers, wigmakers, and textile workers. It underscores the highly material underpinnings of this seemingly frivolous fashion. Curator: And the “deshabillé” aspect is fascinating, the implication of casualness juxtaposed with such elaborate dress. It attempts to communicate an effortless status. Her stance, even the presence of the little dog, speaks to a privileged, carefree existence—a specific form of femininity being carefully constructed. What does that construction exclude? What ideals does it impose, especially regarding race and access? Editor: Right! We can see how social meaning is constructed through and embedded within materials. Even something seemingly minor, like the fabric dyes, indicate wealth and access to global trade routes, reflecting a world increasingly interconnected by material flows and colonial power. It speaks of the rise of consumerism. Curator: It invites a contemporary reading, forcing us to acknowledge the power dynamics inherent in visual representation. How does the visual construction of the female form then intersect with race, class, and social mobility? To me it highlights both power and also oppression in an era soon to be overthrown. Editor: Ultimately, the material tells the story. It points us towards labor, production, and the consumption that drives social division and stratification in France in 1785. Curator: Precisely, seeing art this way encourages us to dissect narratives of identity and beauty and consider whose stories have been marginalized. Editor: The dialogue between the visual and material gives us much to discuss.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.