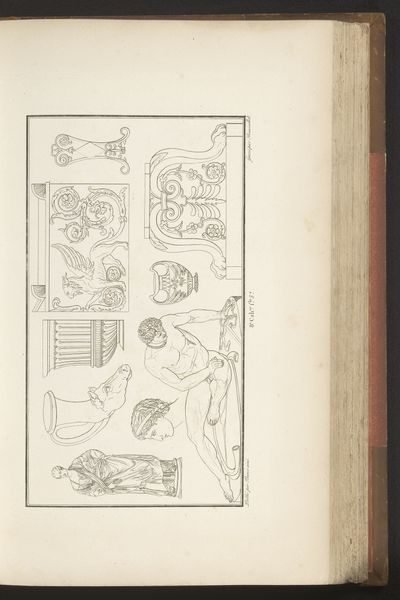

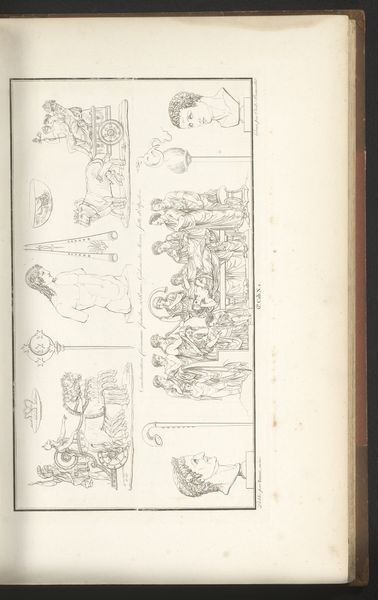

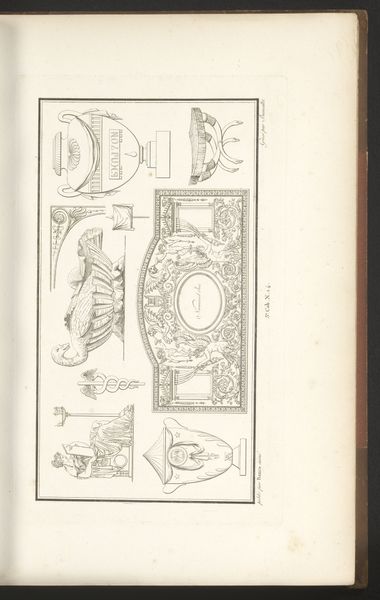

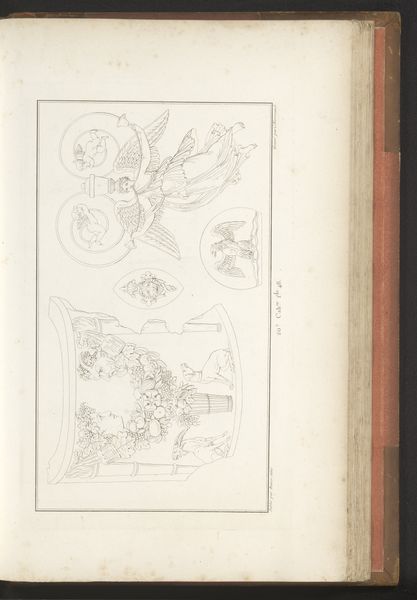

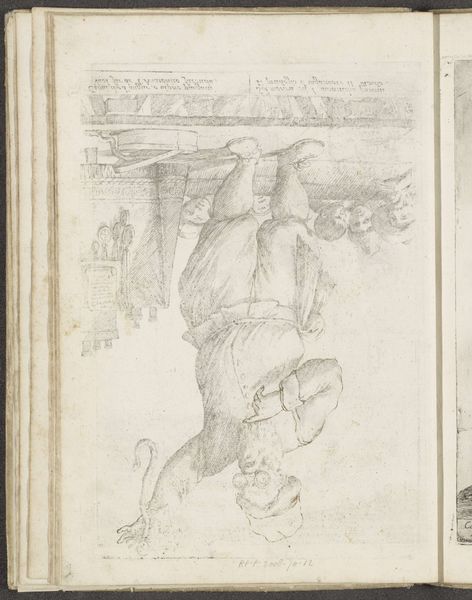

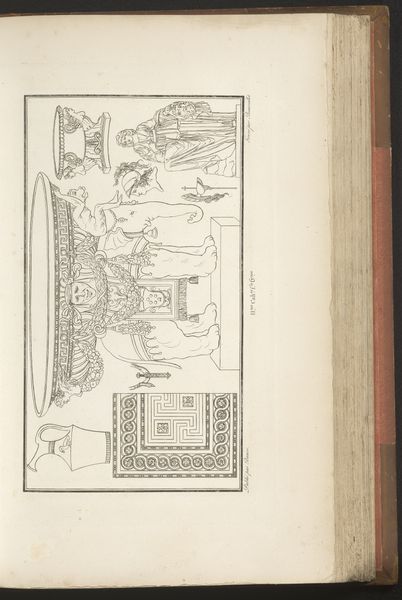

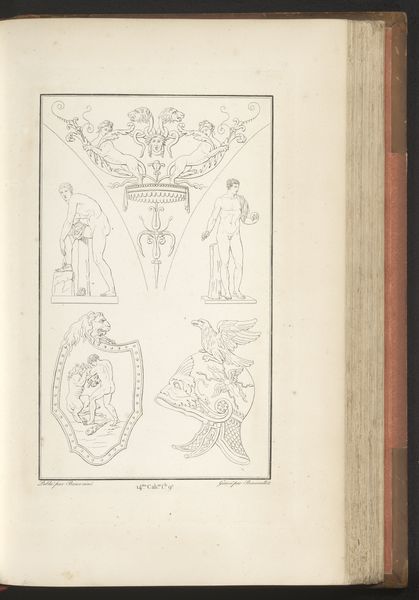

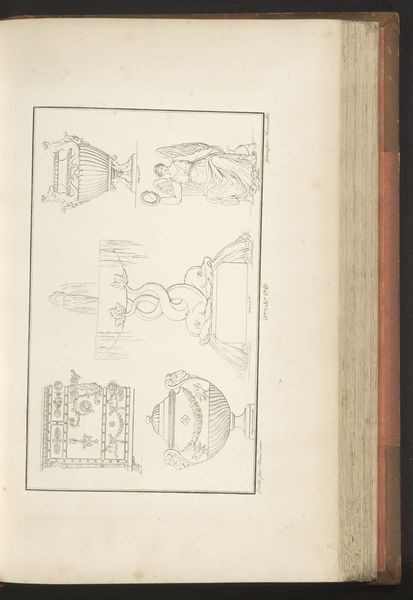

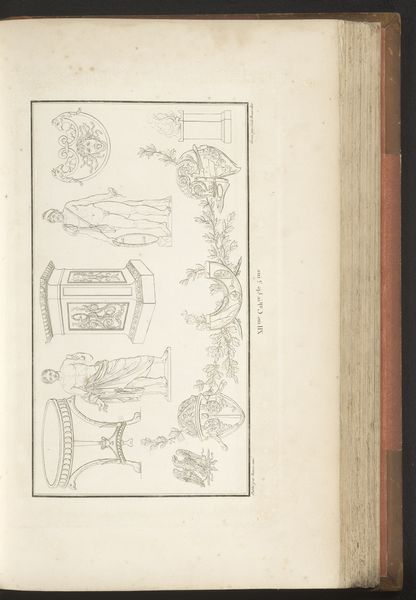

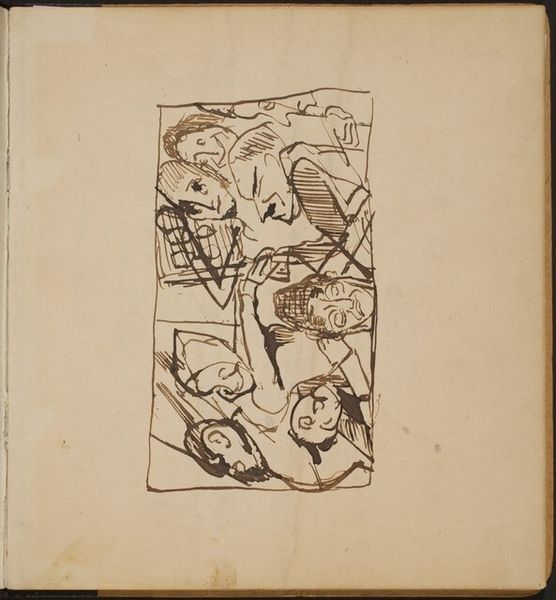

drawing, pencil

#

drawing

#

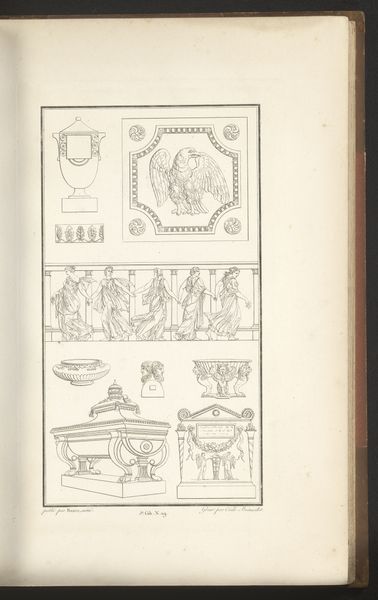

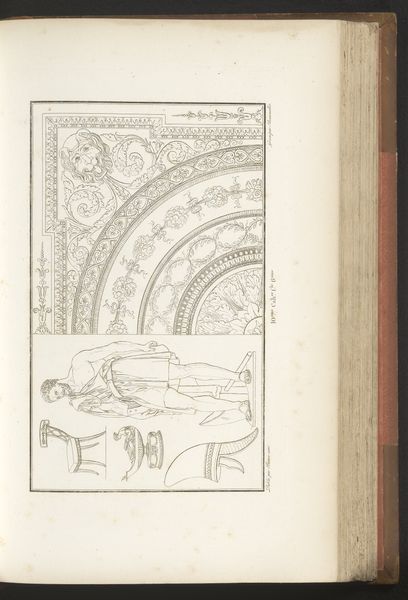

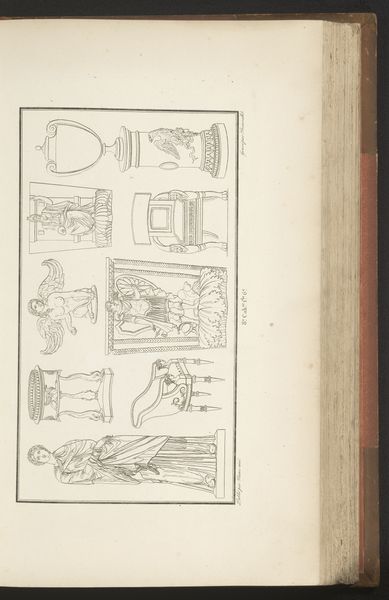

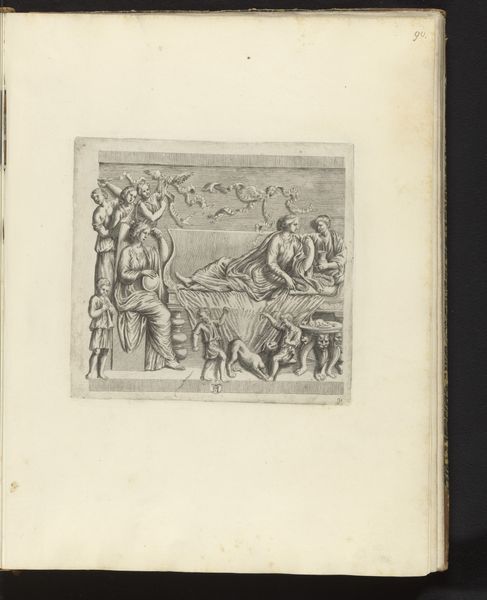

neoclacissism

#

figuration

#

pencil

#

line

#

academic-art

Dimensions: height mm, width mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is "Zittende Vrouw," or "Seated Woman," a pencil drawing dating back to 1820, created by Cécile Beauvallet. Editor: My initial reaction is a sense of fragility. The lines are so delicate, almost skeletal in their depiction. It feels less like a finished work and more like a collection of ideas in development. Curator: Indeed. Considering it’s a work from the Neoclassical period, the artist likely conceived this as part of academic training. Beauvallet's focus appears to be replicating the classical style, specifically looking to integrate classical figuration, seen with the seated figure in profile and various other partial figures on display here, some potentially military in nature. It presents not just one image, but multiple figures in one field of examination. Editor: Yes, there’s an interesting juxtaposition here. We have a seated figure rendered in fairly lifelike detail—considering—with classical ornaments or studies. Does that tell us anything about the societal role of art or drawing education in Beauvallet’s context? Was this accessible to women or typically encouraged at the time? Curator: Certainly, though we lack concrete specifics for Beauvallet, understanding broader patterns remains informative. Academic art training during this era, particularly for women, often had very explicit bounds. While they could certainly study it, figure drawings, which were considered the pinnacle of artistic training, were often not available to them, let alone direct engagement with the body or in history paintings, relegating women to portraiture, and scenes of still life. So this image shows the ways that even within academic settings and formal training, we still see very specific bounds for gender roles being inscribed on them. Editor: It makes one ponder the status of line work then as well: was drawing regarded a preparatory step for painting? Does that inform whether this was displayed or purely functional as an item of process? Curator: That's the heart of it, isn't it? During the 19th century, we observe a shift. Previously viewed merely as preliminary, drawings gradually attained artistic merit, as unique works that showcase the creative's process. Examining the physical artifact of this drawing – the type of pencil used, the quality of paper available at that time and where the materials originated – might further clarify whether it was designed for public viewership. Editor: So this seemingly simple sketch opens up fascinating questions about artistic training, gender roles, and even the evolving perception of art itself. Curator: Absolutely, what may look like simple exercises point toward really rich understandings of both artistic education as well as social understanding and the artist’s positioning at this time.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.