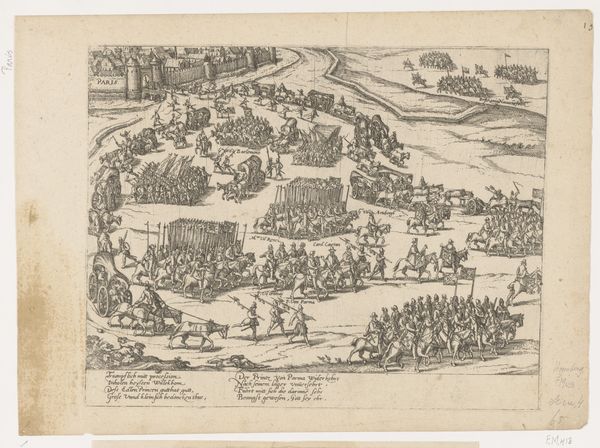

print, etching

#

narrative-art

# print

#

etching

#

mannerism

#

cityscape

#

history-painting

Dimensions: height 407 mm, width 558 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

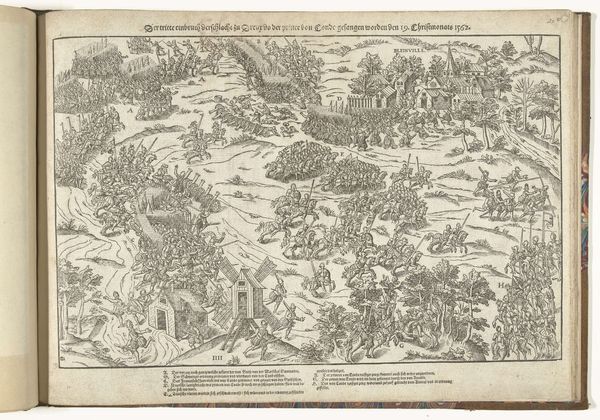

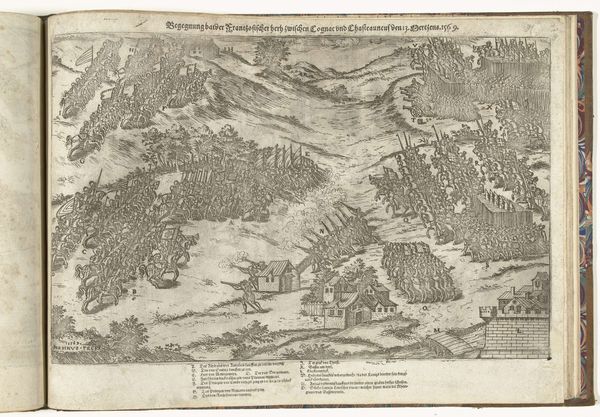

Curator: Jean Perrissin created this etching, "Slag bij Saint-Denis," sometime between 1569 and 1575. It portrays a panoramic view of the Battle of Saint-Denis. Editor: My first impression is a controlled chaos. The scene pulses with the sheer density of figures and implements, all meticulously rendered with that crisp line work. Curator: Indeed. Look at how the artist used etching to create an atmosphere filled with the tension of this battle scene. Notice, for example, the repeated lances in the central army...the repeated angles seem almost geometric, abstracting the sense of movement in the overall conflict. The composition reflects a highly conventional mode of historical representation—the battlefield spread before us. Editor: But the level of detail elevates it. Think about the sheer labor involved in creating so many tiny, distinct lines. The process of etching itself, using acid to bite into the metal, feels violent, mirroring the very event being depicted. You can almost feel the artist leaning into the resistance of the material. Curator: Yes, and it resonates with symbolic meaning! In Mannerist art, this visual density, this abundance of figures and activity, often signifies the chaos of earthly life, but it can also be an allusion to the futility of war. Notice the chaotic field extending toward the town and country landscape. These all convey a symbolic interpretation of temporal instability and earthly suffering, as seen in Christian religious art. Editor: That's an interesting take, how religious symbolism is applied to history. And the social implications of printing at the time, the proliferation of these kinds of images allowing for wide circulation of interpretations. Were the lances, horses, costumes, and artillery all rendered in a realistic mode, based on observed social details? Or did some symbolism inhere within such forms? Curator: Considering the time in which the print was executed, they likely held very specific connotations. This battle has taken on almost mythic proportions by the time it was turned into an etching, don't forget. So Perrissin wasn’t simply creating a replica, but an interpretation embedded with symbolism and lessons. Editor: It's this tension between the material production, and the enduring social function of such printed images, which I think provides such a rich and intriguing case for rethinking what we think we know about the image, and images as vehicles of historical knowledge. Curator: Precisely. An intricate combination of process, observation, and symbolic meaning, capturing more than just a historical moment.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.