Dimensions: height 361 mm, width 245 mm, height 53 mm, width 30 mm, height 49 mm, width 29 mm, height 28 mm, width 45 mm, height 23 mm, width 136 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

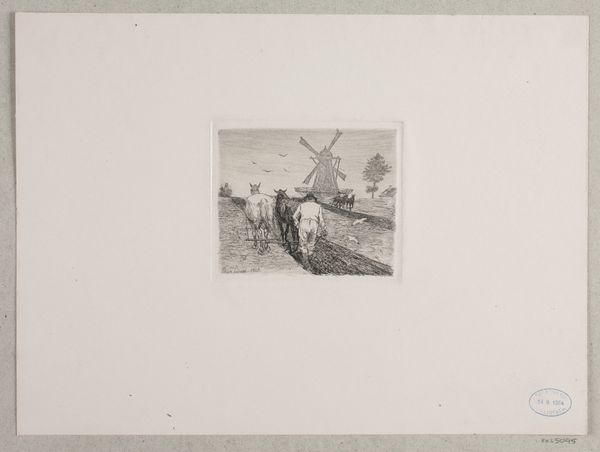

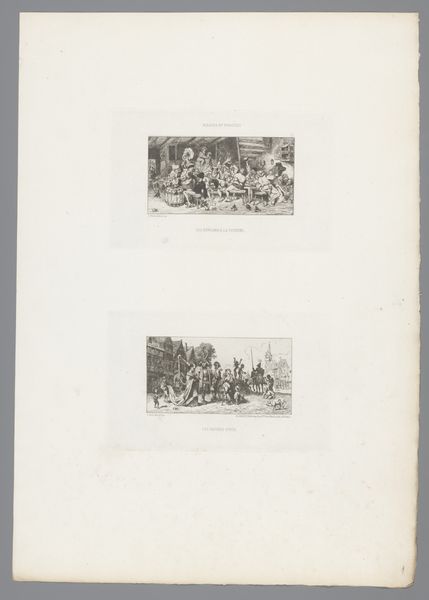

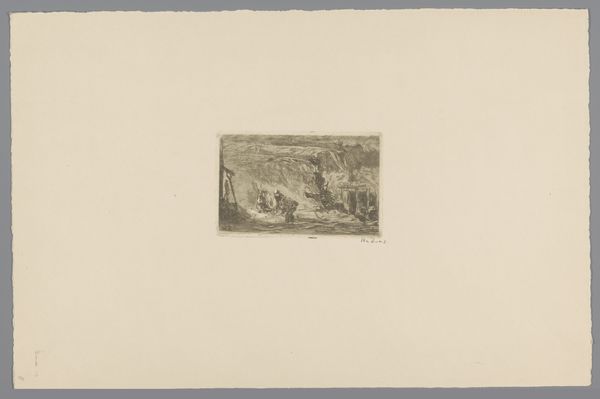

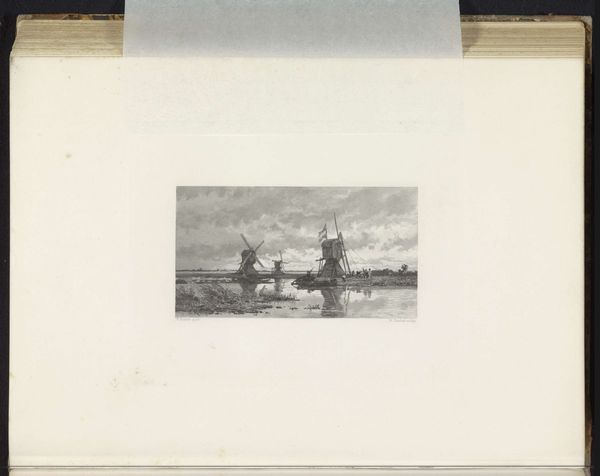

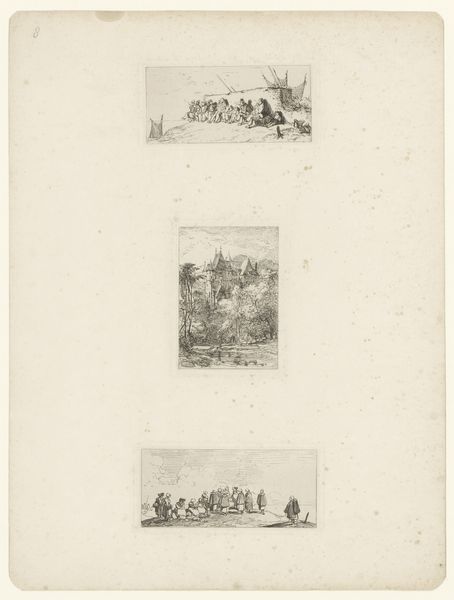

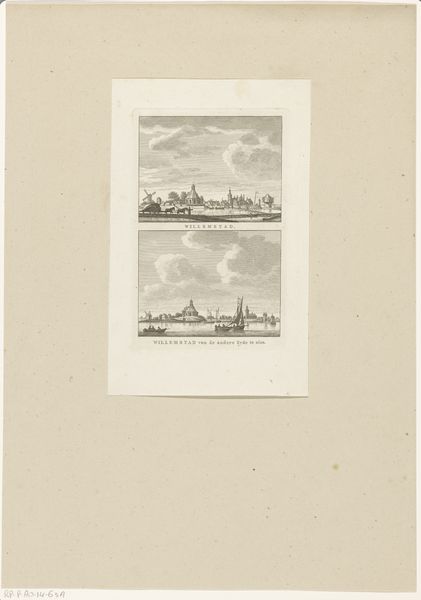

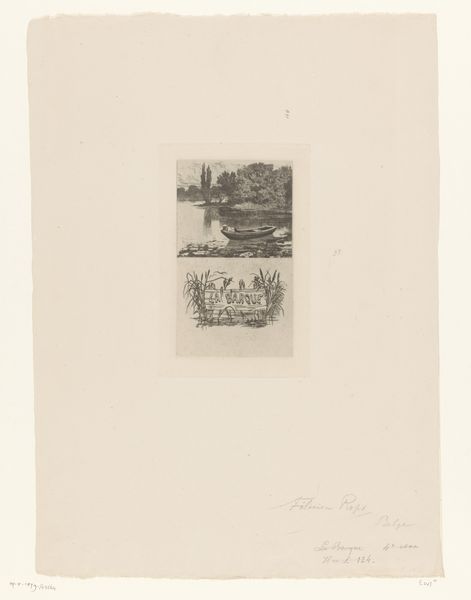

Curator: Let's discuss "Blad met vier prenten met figuren en landschappen", a work made sometime between 1831 and 1904 by Arnoud Schaepkens. The piece consists of four distinct miniature etchings arranged on a single sheet. We see drawings and prints combined using etching, pen, and other techniques. What's your initial impression? Editor: These small vignettes seem incredibly intimate and a bit melancholic. There’s a quiet stillness in the landscapes, and the figures have a sort of solemn quality. I'm immediately drawn to the image of the donkey; it looks both tired and wise. Curator: Indeed. The work resonates strongly with Romanticism, an artistic movement that really thrived in the 19th century. You notice, how landscape served not merely as backdrop but as an active agent shaping the experiences and the psychological states of individuals. This collection by Schaepkens encapsulates many central concerns within European Romanticism. Editor: Right, the choice of medium and the diminutive scale play into that romantic sensibility, emphasizing a sense of personal connection. And while nature takes centre stage, so too do depictions of men—are we romanticizing their labor, maybe, through a softened lens of nature? Curator: The romantic era wasn’t without its contradictions, so you make a great point. Though figures and landscapes take form within these small prints, let's consider that their intimate scale may have also shaped viewing practices. Instead of grand, public consumption we're looking at something delicate and inherently private, something to contemplate with only a small group or even alone. Editor: Definitely. Given the time period, I can't help but think about how these kinds of works might have functioned in terms of circulating ideas about nature and rural life, potentially influencing how people perceived both themselves and the changing landscapes around them, during this period of intense industrial growth. The image of the donkey especially raises questions of labor and class, doesn't it? Curator: That's insightful, placing these prints in dialogue with emerging socio-economic concerns. The blend of figuration and landscape is important here. Each small print provides its own narrative. Editor: These aren’t just pretty scenes. I think they reflect the societal anxieties and the changing relationship between humans and their environment that really mark the romantic era. Curator: Precisely. These prints really are powerful in capturing the emotional intensity tied to historical progress, and they provoke us to consider how it changed. Editor: These tiny portals into the past leave us thinking, perhaps, about what progress really means.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.