painting, oil-paint

#

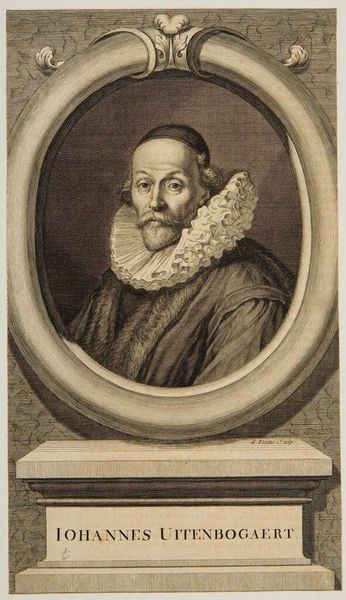

portrait

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

charcoal drawing

#

mannerism

#

portrait drawing

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

italian-renaissance

#

portrait art

#

fine art portrait

Dimensions: height 113 cm, width 85 cm, depth 6 cm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have a portrait painting of Steven van Dalen, who died in 1586, though the artwork is estimated to have been created sometime between 1580 and 1649. It's rendered in oil paint. I’m struck by how the texture of the paint and the sitter's dark clothing convey such a somber mood. What stands out to you? Curator: Looking at this piece, I am most interested in the material reality of its creation and its existence. Consider the linen or hemp canvas, its weave painstakingly prepared to receive layers of ground pigments bound in oil. What sort of labour was required to prepare that canvas? How were the pigments sourced and ground? And then what was van Dalen’s social standing for him to have had his portrait painted, let alone rendered in such costly materials? The material says as much as the man in the painting. Editor: That’s fascinating! I hadn’t really considered the social implications of something as basic as the paint itself. Were there specific workshops or guilds that controlled the pigment trade? Curator: Exactly. The pigments, the oil, the brushes—all products of specific workshops and trade networks. Think about the artist's studio as a site of production, reliant on skilled artisans and global trade routes to acquire the necessary materials. Each element embodies economic relationships of its time. Even the craquelure, the cracking in the paint, can tell a story of environmental impact and conservation efforts, underscoring the painting’s existence as an object with its own biography and relationship with the human labor used to keep it intact. Editor: So by examining the materials and the process, we can actually learn a lot about the economic and social structures of the time? Curator: Precisely! It invites us to rethink this ‘portrait’ not just as a representation of an individual, but as an artifact of material culture. The canvas becomes a record of a confluence of skills, trades, and even global exploitation of resources, as with the provenance of some oil paints. Editor: That gives me so much to think about, and really changes my view of the artwork. Curator: For me, viewing artworks this way makes their social lives as fascinating as their aesthetic properties.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.