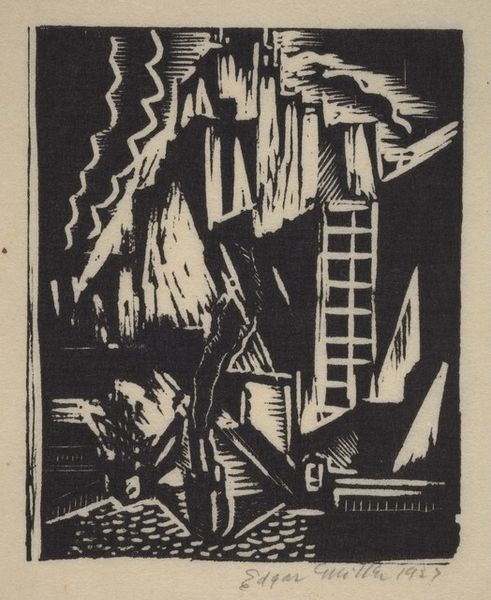

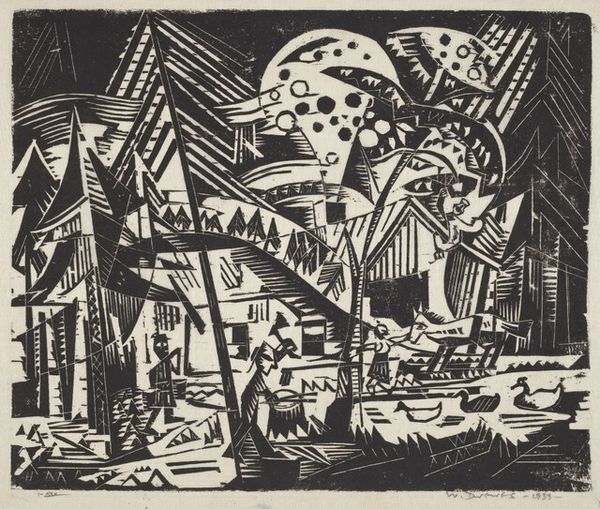

print, woodcut

# print

#

landscape

#

soviet-nonconformist-art

#

expressionism

#

woodcut

#

cityscape

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

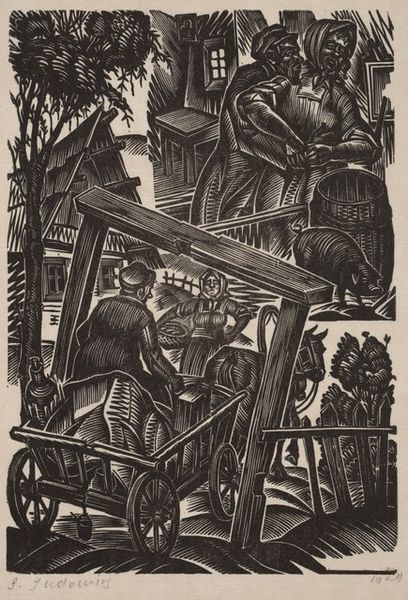

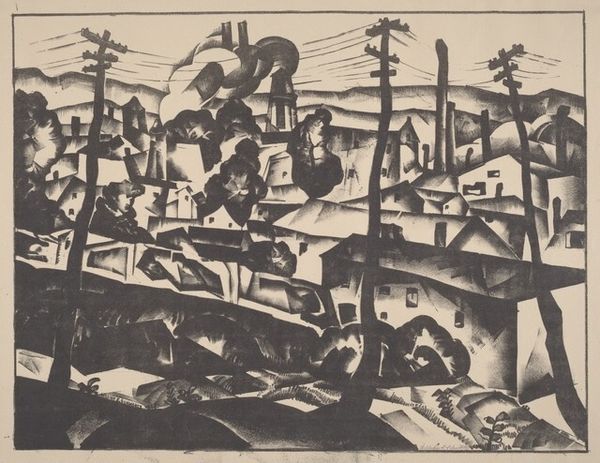

Curator: I find this scene haunting. There’s an intense moodiness to it. Editor: We’re looking at Solomon Borisovich Judovin’s “Woman at the Well,” a woodcut print from 1926, placing it squarely in the Soviet era. Curator: Woodcut! That explains the starkness, the high contrast. Every line feels carved with intention. You know, it reminds me a bit of early German Expressionism, but with this distinctly Soviet flavor. There’s something about the way the buildings are stacked, almost precariously, on the hill...like a child's haphazard blocks. Editor: Precisely. The buildings, the church looming in the background, speak to a community, yet the focus is on the labor, the well as a social, rather than purely domestic space. These black and white prints served a social function. Judovin and his contemporaries documented daily life with its hardships but also quiet dignity. It's more than just illustration. It is about capturing the soul of a place and its people. Curator: That single light window really does capture something special, it gives such life to what could otherwise be an unforgiving townscape, as does the position of the well being close to the heart of the village. A necessary but welcome part of daily routine. You get this strong sense of communal spirit and I’d never expect such from an old black and white print! Editor: These artists grappled with modern identity under evolving sociopolitical constraints, trying to find space within the confines of socialist realism, which celebrated work and the collective while also trying to find some aesthetic means of communicating to a wider range of people. Curator: Do you think people picked up on it, then? These underlying tones? I wonder if they understood these layers, even unconsciously, recognizing themselves and their struggles in these angular forms and demanding perspectives. Editor: Some, certainly, would have been more critically literate towards it. But art also creates conversations; debates which percolate throughout society to slowly affect culture and politics. Judovin, I believe, was contributing his vision of society and that itself becomes important over time. Curator: It does indeed. And the sheer weight of history that these simple tools—the well, the buckets—carry! To be a simple daily job now raised to this striking portrayal of something quietly monumental. That's an impressive weight, isn't it? Editor: A weight and worth we can recognize still, so many years on. Thank you, Judovin, for documenting this weight in an incredible snapshot of this city.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.