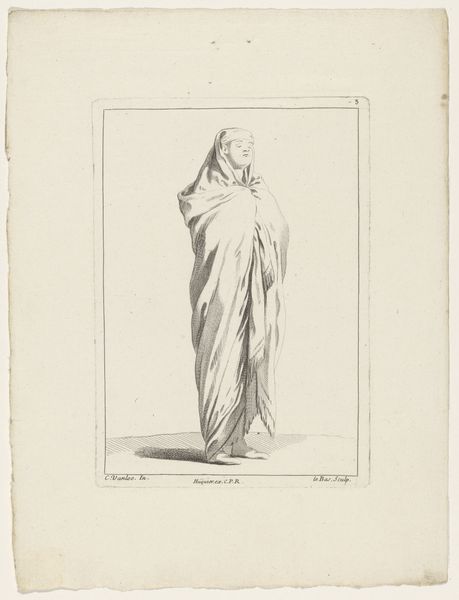

Vrouwenfiguur met gebroken zuil en ruitvormig schild 1781 - 1858

0:00

0:00

drawing, paper, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

pencil sketch

#

classical-realism

#

figuration

#

paper

#

form

#

column

#

pencil

#

line

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

Dimensions: height 190 mm, width 120 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have a drawing titled "Vrouwenfiguur met gebroken zuil en ruitvormig schild" by Bernard Eugène Antoine Rottiers. Created sometime between 1781 and 1858, it’s a pencil drawing on paper. What strikes you immediately? Editor: There's an air of melancholy surrounding this woman, despite the classical elements. She looks weary, perhaps defeated. Curator: The broken column and shield are symbolic. Broken columns frequently represented mortality, or even fallen empires, during this period. Shields speak to protection and perhaps the defense of certain principles. Editor: It feels more personal than political to me. Looking at her gaze, she is not engaged in active combat. She looks like she’s in mourning, and to me, her face speaks to an interiority, an exhaustion of being made to bear these historical burdens that you describe. Curator: I can see that. It’s interesting to note how the artist positions her. She's framed by these symbols, suggesting their inseparability. This era saw a real interest in the role of women and citizenship, which influenced art produced at the time. The sketch seems related to similar Neoclassical representations depicting female virtue and patriotic duty. Editor: But is it necessarily about *virtue*, or about the burden placed upon women? Notice the contrast between the idealised face and the realistic depiction of the hands. She is actually holding that pillar! The drawing complicates a straightforward reading of simple patriotic virtue, I believe. The work almost underscores the difficulty, maybe even the impossibility, of maintaining those ideals. Curator: I think there's merit to both interpretations. Academic art of this time certainly held specific didactic intentions. Consider also, though, how Rottiers places her slightly above us, conveying some element of enduring strength, even in ruin. Editor: Ultimately, I'm drawn to the tension between what she’s meant to represent and what the artist reveals about the cost of that representation. It asks us to consider who benefits from idealized notions of virtue, especially when they mask lived realities. Curator: A fascinating point. The beauty of historical analysis is that it allows us to see the layers, the intended messages, but also to be alive to what remains unsaid and open for interpretation. Editor: Precisely. I think this work allows us to ask necessary questions about gendered expectations of the time, as much as the politics of imagery during the artist’s lifetime.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.