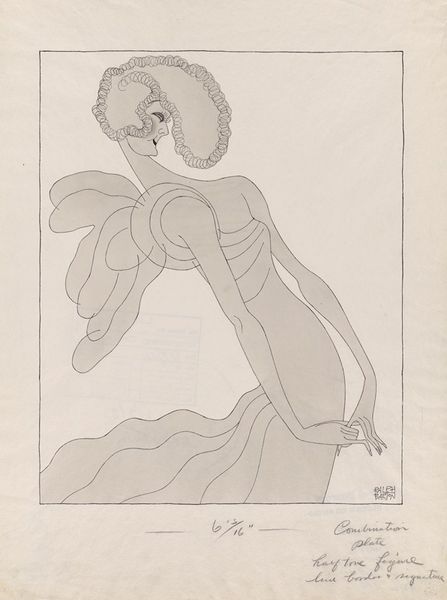

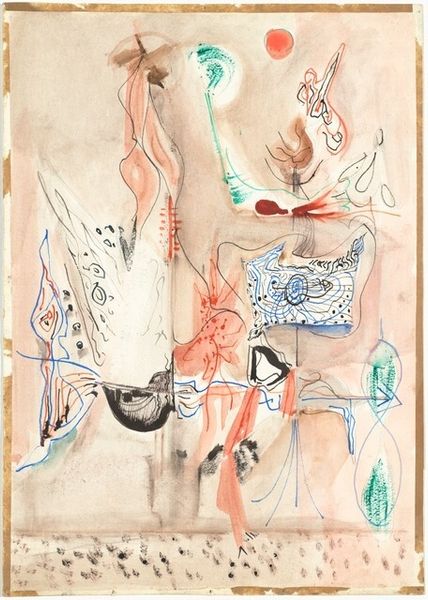

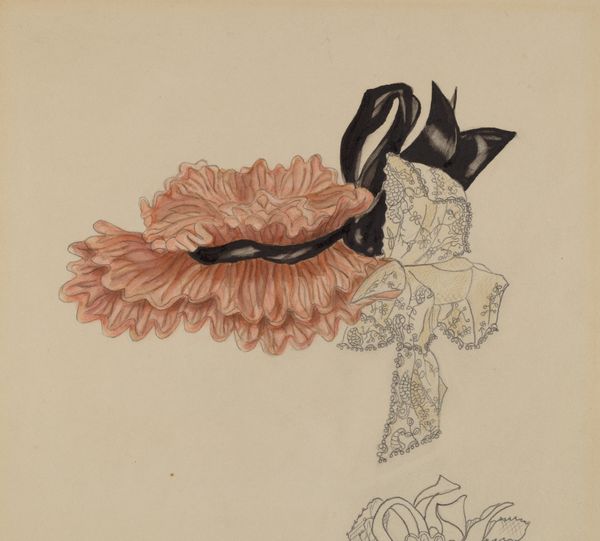

Bagot, costume sketch for Henry Irving’s Planned Production of King Richard II

0:00

0:00

drawing, paper, watercolor

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

paper

#

11_renaissance

#

watercolor

#

watercolour illustration

#

history-painting

Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

Curator: Well, isn’t that something? An explosion of pattern and… almost playful shapes, in a historical context? Editor: Indeed. What we have here is a costume sketch by Edwin Austin Abbey for Henry Irving’s planned production of King Richard II. Though undated, the work is rendered on paper using watercolor and pencil, offering us a glimpse into the material considerations for a theatrical spectacle rooted in Renaissance history. Curator: Those smiling, almost cartoonish shapes all over the cloak… against that stark, authoritative red. It's so unexpected. Do you think they signify anything in particular about the character, a secret joviality perhaps? Editor: The consistent repetition of this shape implies something about mass production, actually. These costumes, however luxurious they appear to us now, were likely to have been realized with a specific budget and labor force in mind. Perhaps those "smiling" shapes are less about symbolic intent and more about practical means of application and visual impact on a large stage. Think of the stencil work or block printing that may have influenced the creation of this design. Curator: A theatrical piece always carries the weight of cultural history. The decision to portray Richard II, the choices regarding his appearance—down to the pattern on his cloak—speaks to an intended reading of the historical narrative. The choice to soften the red of royalty with these "smiling" shapes can soften a villain, maybe? It allows an audience a way in to feeling, thinking about the choices that created a character rather than dismissing one. It may want us to remember what humanity remains. Editor: An interesting interpretation, but if the material means influenced the forms, how much "humanity" can we realistically project onto the textile decisions? Labor practices are human as well. Did the artists working the textile on such projects bring anything "human" into the art as well? The means matter. Curator: But isn't that the point? Every artistic choice—materials, techniques, even the speed of production—is loaded with symbolic weight precisely *because* it reveals something about the cultural values, the collective imagination of the era that produces it? It’s as if this flamboyant garb attempts to hold on to what came before the Industrial Revolution as technology advances quickly forward, trying to pull at memory, continuity in life. Editor: Fair enough. Looking closely, it seems Edwin Austin Abbey did make a deliberate connection between means and symbols here. It feels more complex now. Curator: I find myself wanting to see the show now. Editor: Agreed! Let’s hope someone reconstructs this unrealized production, honoring both the symbol and its materiality.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.