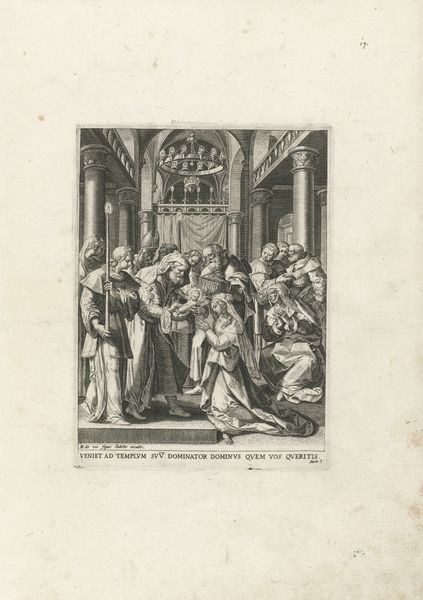

print, engraving

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 188 mm, width 146 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

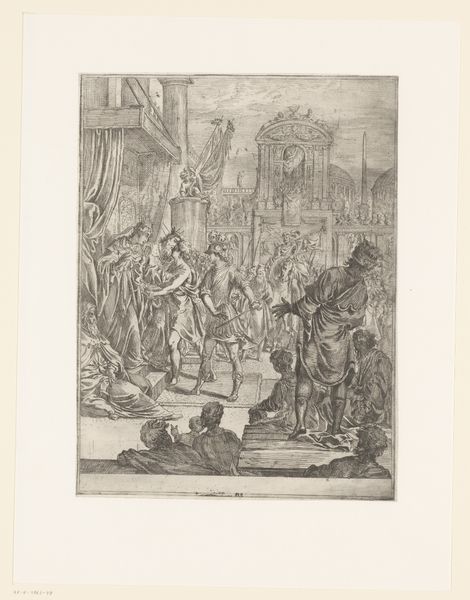

Curator: What a powerful image of human suffering! It feels incredibly dramatic, even in this small engraving. Editor: Indeed. This is Abraham Bosse's "Emilie en Camille vinden de gewonde Melinte en Palamède," created in 1639. It's a print, an engraving to be precise, currently held in the Rijksmuseum. Bosse was known for his detailed depictions of contemporary life, but here he tackles a scene of classical drama. Curator: It does evoke a stage. The classical architecture in the background certainly contributes, as does the balcony overlooking the event. Is that an eternal flame that I see in the temple behind? Editor: Very perceptive! That eternal flame underscores the weight of this scene. The iconography points us to sacrifice and remembrance. The limp bodies clearly represent loss, possibly violent death given their state, yet there's also an element of discovery in the children finding them – a rebirth, perhaps? Curator: So it is a history painting! This engraving is Baroque in style and it is, like many Baroque artworks, full of passion and motion, while set against the stagecraft and the clear separation between observer and observed as was fashionable in 17th Century drama. What strikes me is the power of its social messaging, of finding the hurt and then displaying them, even putting them into the spotlight, in a way we still find impactful in our culture today. This would have spoken directly to contemporary notions of honour, heroism and public grief. Editor: Precisely. The wounded figures, likely soldiers or heroes in their time, laid bare like this evoke not only pity, but demand attention to the realities of conflict that resonate across social strata. And Bosse subtly utilizes the linear quality of engraving to create dramatic diagonals that pull our eyes down to the dying, making them unavoidable. Curator: Yes, the composition draws the eye right to the suffering figures on the ground. Their vulnerability is so poignant. Editor: Considering Bosse's background and the historical context, I see his choice of this scene, rendered in such detail, not just as an artistic statement, but a commentary on war, honour and social obligation during the Thirty Years' War. It also shows that finding compassion might be done even when observing grief and suffering at one remove, a form of public acknowledgement that must happen before true recovery and forgiveness can happen. Curator: An artistic decision which shows us just how well the choice of image and style still speaks to audiences today. Thank you for helping me see more. Editor: The pleasure was mine; now I will be looking more closely at the power of witnessing tragedy.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.