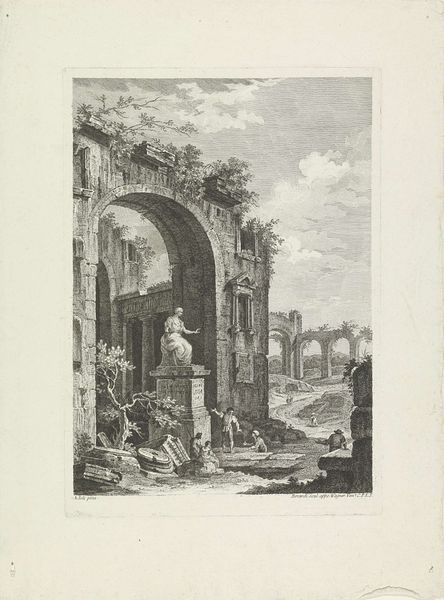

Doorkijk onder gewelven naar ruïnes en standbeelden met enkele figuren 1739 - 1740

0:00

0:00

giulianogiampiccoli

Rijksmuseum

print, engraving, architecture

#

architectural sketch

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

cityscape

#

history-painting

#

engraving

#

architecture

Dimensions: height 248 mm, width 346 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

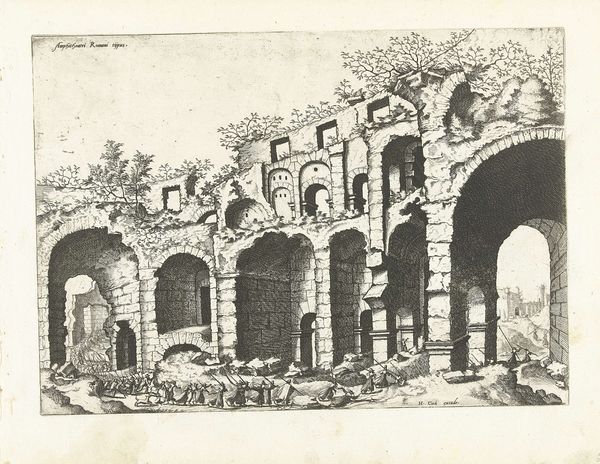

Curator: Look at this captivating print, “Doorkijk onder gewelven naar ruïnes en standbeelden met enkele figuren," or "View Through Vaults Towards Ruins and Statues with Some Figures," created by Giuliano Giampiccoli between 1739 and 1740. The print is a beautiful engraving, full of intricate details. Editor: It evokes a melancholic and contemplative mood. The ruins suggest decay, a civilization past its peak. There's also an emphasis on light and shadow created with crosshatching that defines every object. It makes you wonder about the role of human presence in a world of impermanence. Curator: Right. Giampiccoli's meticulous technique draws attention to the craft of printmaking itself. The crosshatching you noticed is vital—consider how he deployed layers upon layers to create depth, transforming a flat surface into a multi-dimensional scene. We also need to think about the historical context; engravings like this served as visual documents, allowing people to experience places they might never physically visit. Editor: Absolutely, these scenes became tools to build identity narratives and power dynamics for certain audiences. I would argue it also creates a dialogue between the present and a romanticized past, influencing perceptions of history and culture. What’s the socio-political situation that facilitates such nostalgic interest in these images of crumbling ruins? Who gets to decide which ruins, which histories, are deemed worthy of artistic reproduction? Curator: These are vital questions. Thinking materially, the engraving itself—the copper plate, the inks used—connects Giampiccoli to a network of workshops and distribution channels. It speaks volumes about artistic production during that time. It’s worth thinking about the economy of art in that time, about the artist as a craftsperson and merchant, rather than the romanticized ideal of the singular artistic genius that has come to dominate much of art historical discourse. Editor: Right, which pushes the question further, how much was his craft shaped by gender, access to materials, class background and which bodies are depicted to humanize this artwork and legitimize its discourse of ruins? I wonder if Giampiccoli used preparatory sketches for such details. Curator: It's likely he worked from drawings, yes, but this print serves as a testament to the collaborative labor needed to create images that reached wider audiences, allowing art to transcend barriers. Editor: Precisely. By highlighting its cultural, material and historic circumstances we are moving away from thinking of objects only in aesthetic terms. Curator: A testament to the ways in which artistic representation becomes a complex negotiation between vision, labor, and legacy. Editor: Agreed, it helps us deconstruct this art's ability to make claims about historical power and whose legacy is considered.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.