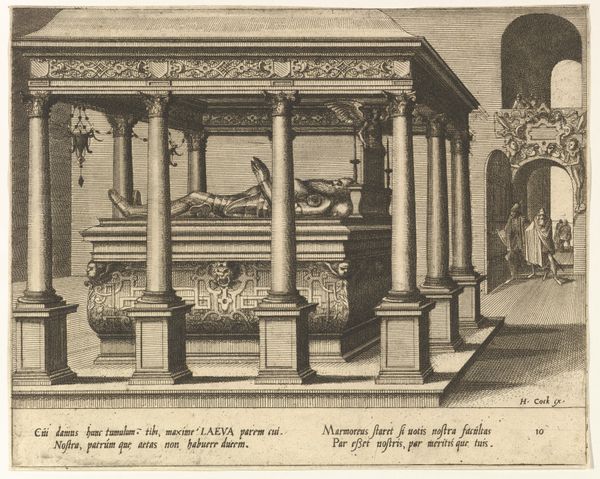

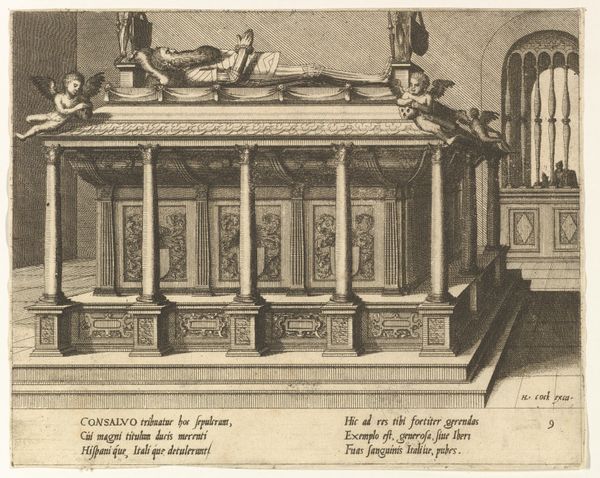

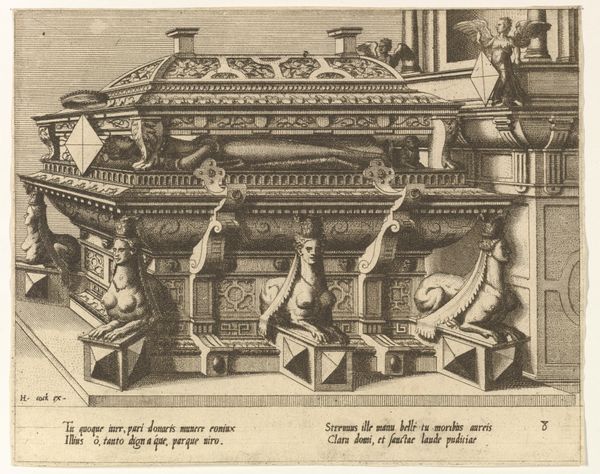

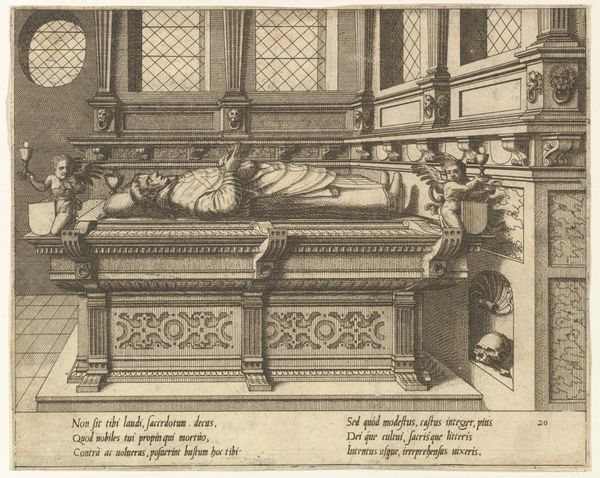

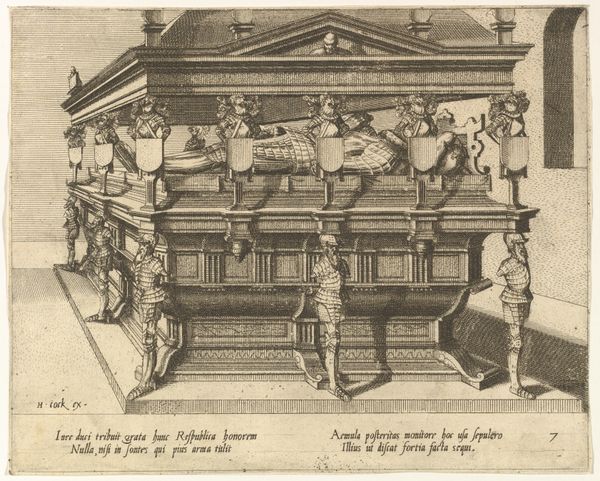

drawing, print, engraving, architecture

#

drawing

# print

#

mannerism

#

form

#

11_renaissance

#

geometric

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

#

architecture

Dimensions: sheet: 6 9/16 x 8 1/4 in. (16.7 x 20.9 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

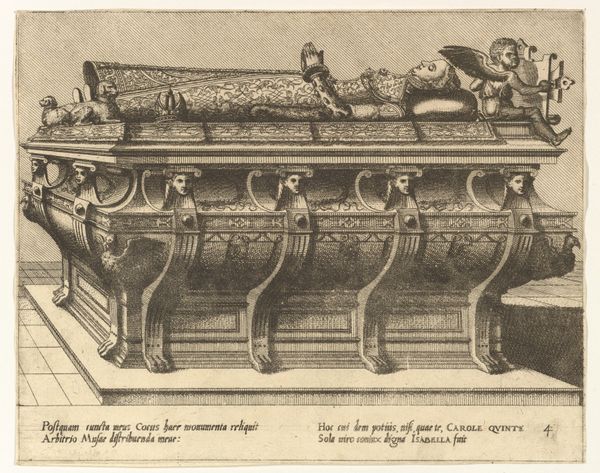

Curator: The initial impression I get from this engraving is one of austere monumentality, a solemn tribute captured in meticulous detail. Editor: Indeed. Let's dive into this impressive artwork. What we have here is "Cenotaphiorum (3)", an engraving by Hans Vredeman de Vries dating back to 1563. The piece resides at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, offering us a glimpse into the architectural fantasies of the Renaissance, where Mannerism held considerable sway. The print itself presents a vision of a grand cenotaph, an empty tomb. Considering that European monarchs often had funerary monuments throughout their empires even if their physical remains were interred elsewhere, who do you imagine this to commemorate? Curator: Given the Latin inscription referencing Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, one could deduce this theoretical monument pays homage to his legacy. It would serve as an architectural assertion of power extending even beyond death, especially in light of the period’s intense focus on dynastic succession and religious upheaval during the Reformation. Editor: I am most struck by the technique. The artist’s command over line work allows us to visually experience a three-dimensional architectural design. Look at the precise rendering of the columns, the decorative friezes, the eagles adorning the substructure—they construct an illusion of volume and depth that's quite remarkable for a two-dimensional medium like engraving. The architectural style combines both classical and fantastical elements, representative of the Mannerist aesthetic of the time. Curator: Absolutely, and let’s also reflect on the purpose such idealized representations would have served. The act of memorializing rulers in grand visual statements often played a key role in shaping collective memory and bolstering political narratives. For the public of the time, it likely stirred a mix of awe and dutiful allegiance, acting almost as state propaganda. The symbolic ornamentation should have acted like visual rhetoric. Editor: I see it also as a reflection of the High Renaissance and its desire to classify all natural forms through the usage of mathematics and reason. So much classical thought returned to the sphere during this time. This rendering attempts to take the mathematical perfection achieved and use it to depict our physical world. Curator: True. And engaging with historical images like this enables us to ponder questions about how societal values were perpetuated or subverted through the language of art and architecture. The grand gesture that Vredeman de Vries gives us should remind us of power and those it intends to memorialize for generations to come. Editor: It causes one to consider how this all maps to the linear forms so carefully rendered. Thank you for pointing that out.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.