#

light pencil work

#

quirky sketch

#

old engraving style

#

personal sketchbook

#

ink drawing experimentation

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pen work

#

sketchbook drawing

#

storyboard and sketchbook work

#

sketchbook art

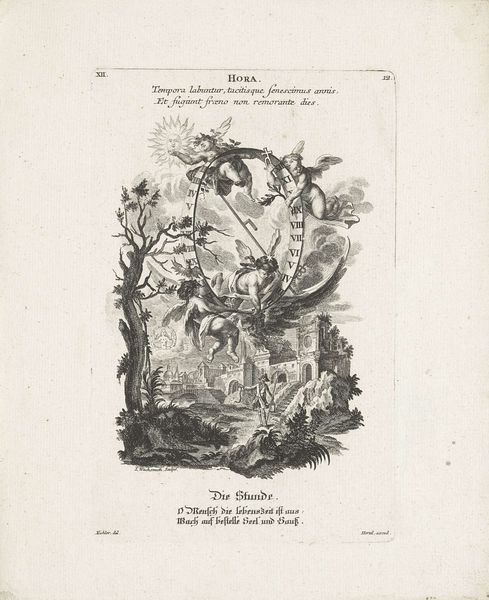

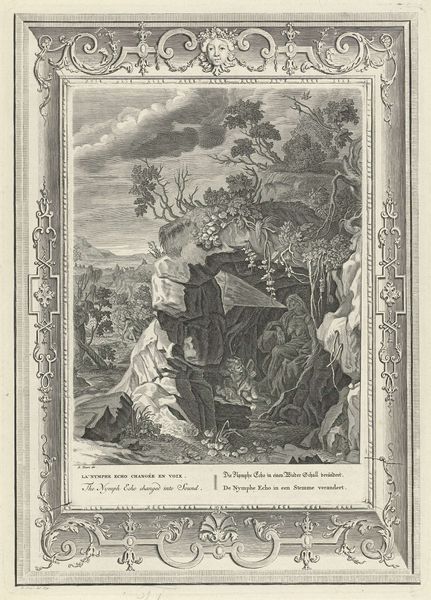

Dimensions: height 194 mm, width 127 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Jeremias Wachsmuth’s engraving, “De Wereld,” created around 1758-1760, offers us a fascinating glimpse into the artist's world view. I’m immediately drawn to the level of detail captured. Editor: It has this rather bleak, slightly absurd air. A shepherd seems to emerge from the wilderness and is facing an arena full of anonymous people. I wonder what exactly he's trying to represent with his pastoral tools and attitude in relationship to a clearly unnatural architecture. The work has strong links to craft techniques: it shows clear work and skillful rendering to depict a material vision. Curator: Exactly! It prompts consideration of labor and the means by which it is structured in this “world.” Consider the placement of the shepherd—ostensibly representing the rural or "natural"— in stark contrast to the constructed labyrinth behind him and, consequently, raising crucial questions about the hierarchies within these constructions. His identity as some mythical figure sets the stage to talk about intersectionality, maybe by focusing on how the male figure's relationship to constructed nature is highlighted by the labyrinthine architecture which represents civilization, perhaps even colonialism? Editor: It does invite such narratives, especially regarding labor in colonial projects. Engravings were reproducible and relatively accessible. To consider Wachsmuth's means, therefore, suggests the broader consumption patterns of the time, allowing those critical insights to be reproduced across various classes. The artist's craft is linked inextricably to colonial structures. I want to look close, what materials were used, how was labor split, who consumed and how did all of this connect with capitalism's rising domination. Curator: By acknowledging those links, we acknowledge art's relationship with social power and resist narrow interpretations, seeing art-making and production as integral elements to the narratives around class, identity and more. I am deeply concerned about how those intersections are understood. Editor: Indeed. So by turning to production means, we gain better critical awareness about consumption and society. The meticulous execution of Wachsmuth opens those avenues to reveal production practices of 1700s that we are now actively challenging as materialists. Curator: Looking at this from an intersectional perspective has definitely highlighted a lot of issues regarding labor and society during that time, and reminds me to look into power dynamics when confronting any type of artwork. Editor: Analyzing craftsmanship reveals structures and social norms; even a relatively unknown piece may yield fresh observations once the process of making has been dissected.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.