drawing, paper, pencil

#

drawing

#

charcoal drawing

#

paper

#

oil painting

#

folk-art

#

pencil

#

watercolor

#

realism

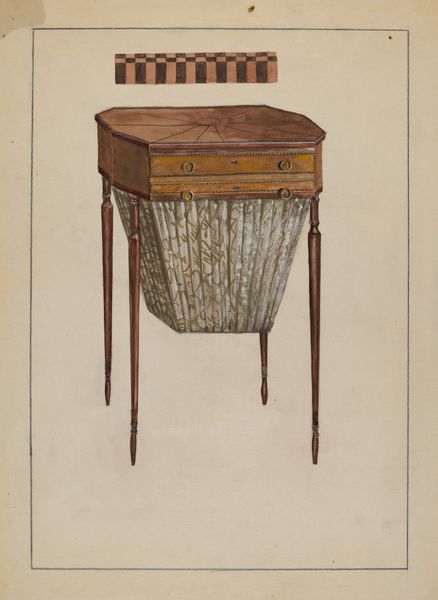

Dimensions: overall: 42.4 x 31.2 cm (16 11/16 x 12 5/16 in.) Original IAD Object: none given

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: Well, hello! Today we’re looking at Rolland Livingstone’s 1941 drawing, "Sewing Table," rendered in pencil, watercolor and charcoal on paper. What’s your first impression? Editor: I’m struck by its stillness, and perhaps even a touch of loneliness. The precise detail almost makes it feel like a specimen. There’s no sense of life around it. Curator: I think the detail is crucial here. Consider how meticulously Livingstone has rendered the wood grain, the delicate drape of the fabric, even the subtle shine on the drawer pulls. This speaks to the labor involved in crafting both the object itself and the artwork. Someone, somewhere dedicated many hours to their craft. Editor: Precisely! And I find myself wondering about that context. What function did this drawing serve? Was it a design, a record, a study of an object meant for a specific social space or even market? Was this artist documenting the domestic objects which define femininity in art? Curator: It makes me wonder if Livingstone focused on rendering the image of everyday life during times of disruption to national infrastructures for making those materials: think of war and limited commodities. And it prompts us to rethink where art meets labor, even at the amateur level. Editor: It’s interesting to ponder the status of the objects represented and what values society places upon them. Is it about mere utility or an intersection with cultural relevance and the historical narratives connected to that? Curator: Absolutely! I see how Livingstone uses artistic material as documentation but simultaneously challenges traditional hierarchies between what we consider fine art versus craft objects of domestic life. It blurs these distinctions. Editor: Looking at it from a social lens, it also sparks broader questions. About taste, gender roles and historical shifts. Museums inevitably curate narratives, highlighting particular threads of these discussions and omitting others. Curator: That’s right. By prompting reflections on materiality, art history becomes much more multi-faceted than surface level perceptions would have it be, challenging assumptions around artistic skill, authorship, and societal valuation. Editor: Indeed. Analyzing art from a materialist or socio-historical perspective invites questioning established canons, bringing richness to our understanding, and helping reimagine its relation to the human experience.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.