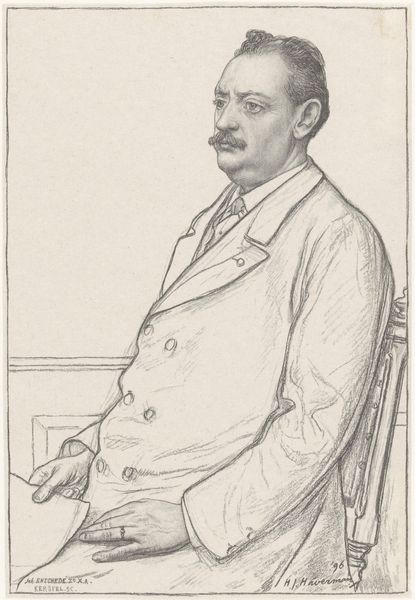

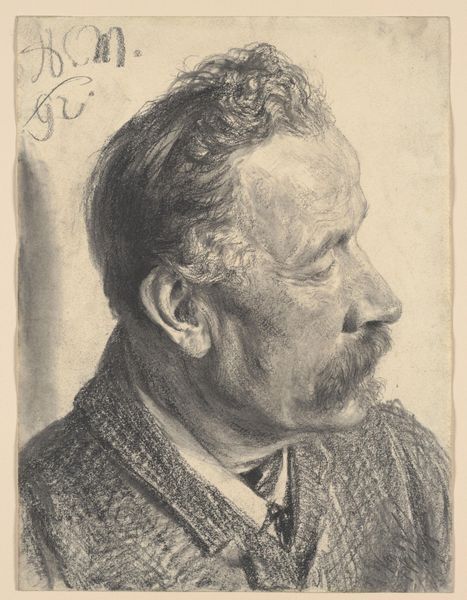

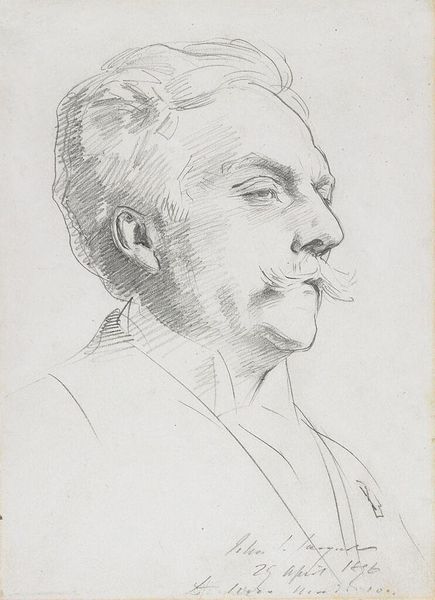

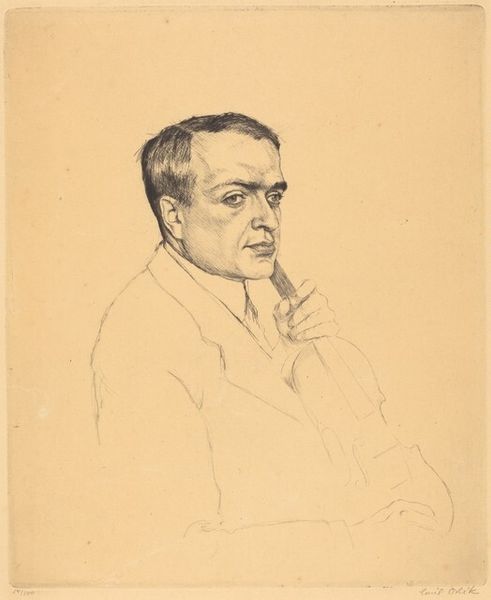

print, etching, graphite

#

portrait

# print

#

etching

#

graphite

#

portrait drawing

#

realism

Dimensions: height 197 mm, width 140 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

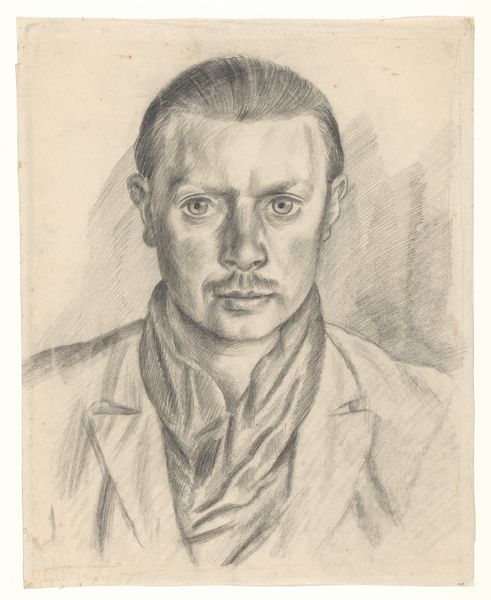

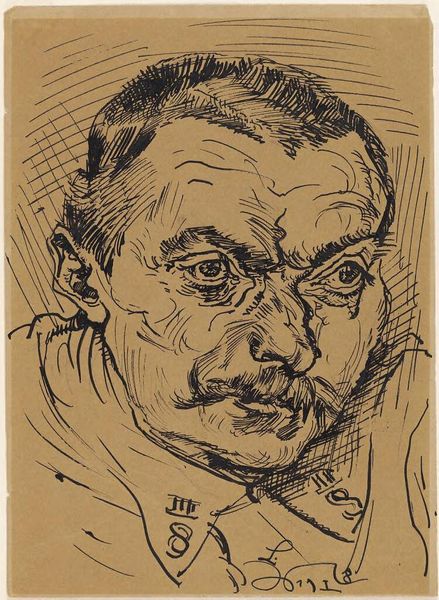

Curator: Gazing at us from 1921, we have Ferdinand Schmutzer's "Self-Portrait," rendered in graphite and etching. It’s a study in monochrome delicacy. What catches your eye first? Editor: It’s the almost mournful gaze, isn’t it? So intense. But also the texture of the etching. It's like a topographical map etched onto his face. Curator: Yes! And considering Schmutzer was known for his printmaking—etchings, lithographs—that textural quality becomes integral. It’s not just *representing* a face, it’s the *process* of the lines making the face that’s so intriguing. One could almost touch the weight of graphite transferred onto paper through printmaking. What do you make of this melding of drawing and print media in a self-portrait? Editor: I wonder about the choices he made in his material production. Realism often masked the means of production but, here, he lets you see it! Also, printmaking at the time, it allowed for wider access than painting to art… making art democratic at the same time as his wealthy collectors. How can we look at the same artwork in these two opposing directions? Curator: Isn't it wonderfully strange? He’s creating this detailed likeness—realism, as you point out—but the visible print work also offers a removal, an abstraction. He reveals *himself*, yes, but filtered through a rather laborious, mechanical process. There's also something incredibly poignant about capturing one’s own image through these layers, as if grappling with your existence and what you want it to become as a piece of work. Editor: And in a time where new mechanical reproduction changed ways of life, right? Is Schmutzer then showing his place as an artist, as artisan, in an age of factories? Was this process about self-fashioning? And could that tell us something about a cultural context? Curator: Exactly, it suggests a subtle tension! Almost like an emotional ambivalence regarding this identity or career, and certainly vis-a-vis progress. What I see, though, in his decision to embrace and highlight the process is a sense of taking ownership, as if saying, "I’m not afraid to show the work because the work *is* the meaning." Editor: Ultimately, a testament to what art makes of labour and what labour makes of art, if you will! Curator: Beautifully said. It certainly encourages a deeper look beyond the image to consider both the process and the intent behind its creation. Editor: Right. Thank you, Ferdinand, for reminding us that what we leave behind is inextricably tied to what we put into it.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.