photography

#

portrait

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

historical fashion

#

19th century

#

academic-art

#

realism

Dimensions: height 84 mm, width 54 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

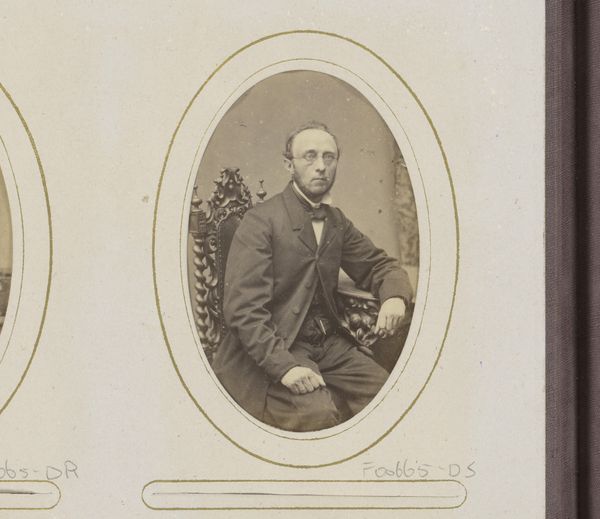

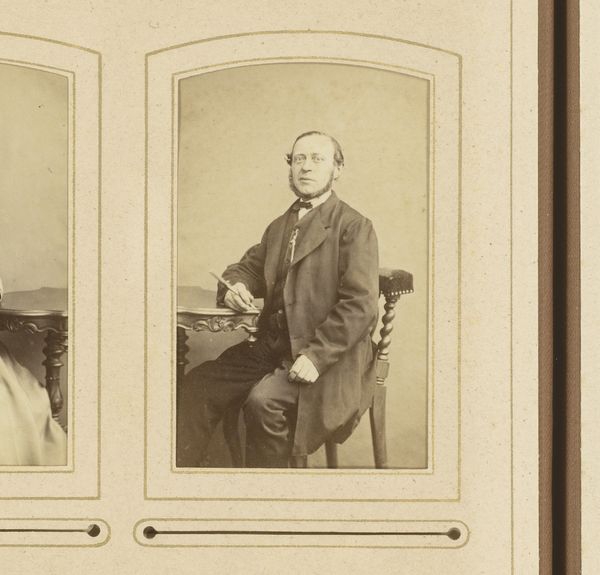

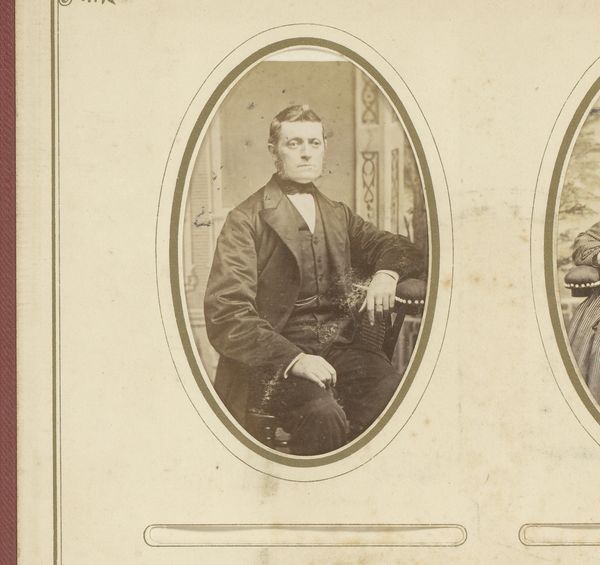

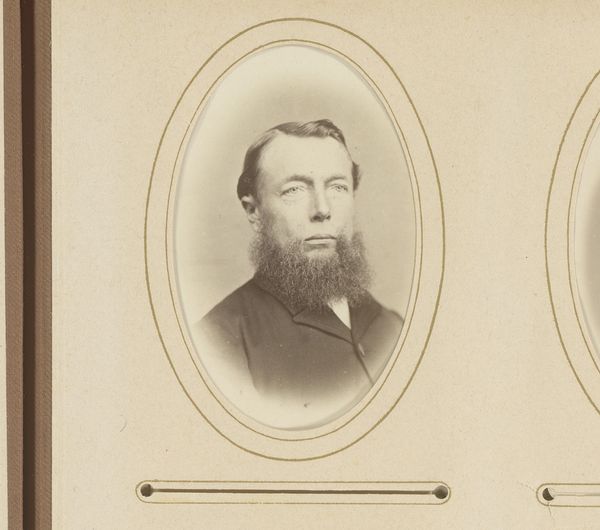

Curator: Here we have "Portret van een man bij een bureau," which translates to "Portrait of a Man at a Desk," dating from between 1859 and 1870. The photographic process itself is our medium. What's your immediate take on this? Editor: A solemn gravity. The oval frame emphasizes the sitter's enclosed world. The gaze is direct, holding you, almost challenging you. I detect hints of stoicism etched in his face, reflecting the era's prevailing mood of restrained virtue and serious purpose. Curator: Precisely. Now, consider how the emerging photographic technology shaped this visual representation. The cumbersome equipment, long exposure times, and the collodion process would necessitate a stillness, a constructed formality that inevitably colored the result. Editor: True. The symbolism feels deliberate, from his dark suit signifying power and influence, to the barely visible desk, implying labor, industriousness. It’s interesting how a material reading reveals so much. This objectification hints at an individual defined by productivity within the context of a developing capitalist economy. Curator: Indeed. Look at how the photographer makes the trappings of 19th-century masculinity apparent—a sort of stiff, upper-lip heroism. This sartorial choice is a means of performing belonging to the upper echelons. It says, “I am one of you." Editor: The dark tones also convey mortality. There is always something in the portrait's capacity to cheat death, capture that soul within this frame, and somehow still make the man appear imposing. Even as time moves on, his symbol persists. The man himself fades away, his cultural imprint endures. Curator: And perhaps a slight commentary on the fleeting nature of wealth. Photographs, once scarce, become increasingly accessible to wider swathes of society during this period. Suddenly, these visual declarations of permanence become mass produced. Editor: Food for thought. I can appreciate how these photographic items allowed middle-class men and women a lasting reminder that time indeed moves on and so did all those important things of this world. Curator: I agree, quite intriguing. These early photographic works present an engaging dialogue of how meaning, power and visual rhetoric all intersect with cultural production and material distribution.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.