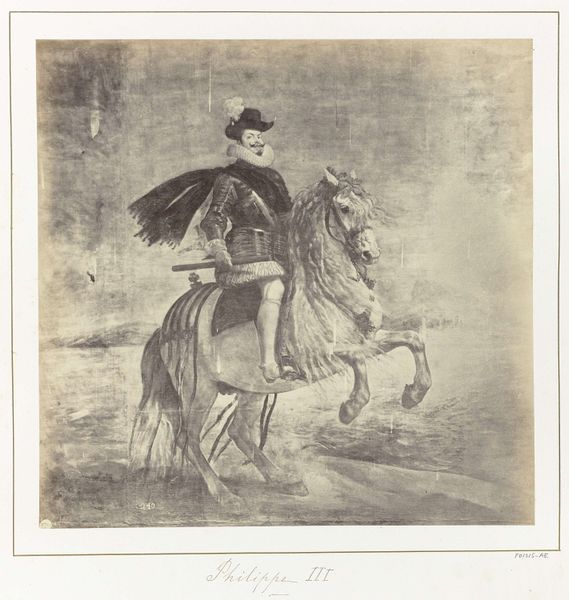

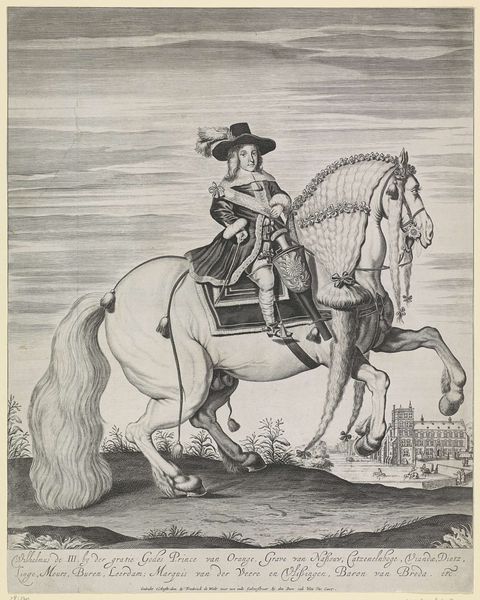

Fotoreproductie van een schilderij door Velázquez, voorstellend een portret van koning Filips III van Spanje c. 1857 - 1880

0:00

0:00

juanlaurent

Rijksmuseum

Dimensions: height 285 mm, width 311 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This intriguing photographic reproduction captures Velázquez's portrait of King Philip III of Spain. Created between 1857 and 1880 by Juan Laurent, it resides here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My initial reaction is the palpable sense of formality and power. Even through the photographic medium, the sheer bulk and texture of the fabrics and metal hint at both status and the weight of the king's position. Curator: Absolutely. Note the deliberate iconography. The horse, reared up as if prepared for battle, symbolizes potency, vitality and strength, echoing Philip's rule, although one could argue the portrait is idealized more than realistic, given Philip III’s actual reputation. Editor: Which makes me think about the process itself. Why create a photograph *of* a painting? Was it about democratizing art, making it accessible in a way that the original, sequestered in a royal collection, could never be? It feels very deliberate, moving the means of image production out of the sole control of painters and into this new realm. Curator: Exactly! It speaks to how cultural memory and power are both preserved and disseminated. The choice to reproduce a Baroque royal portrait emphasizes the era's grand spectacle. But I find myself also drawn to the figure himself: the stoic king sits high on his mount; that stiff ruff around his neck a clear statement of courtly status, a barrier. Editor: Yes, the very tangible details… consider what it means to capture this materiality through photography at the time. How that reproduction changes labor relations or access to portraiture for rising merchant class who emulate these signifiers of rank. The fact this reproduction itself is now in museum displays how the means of mechanical reproduction affects historical interpretation. Curator: Seeing how art is passed down across generations, through the lens, the image remains imbued with meaning. These copies have come to shape understanding, each telling their own silent narrative. Editor: It pushes me to reconsider how something as ‘simple’ as a portrait photograph documents material reality *and* social aspiration across eras. An interesting point to end with.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.