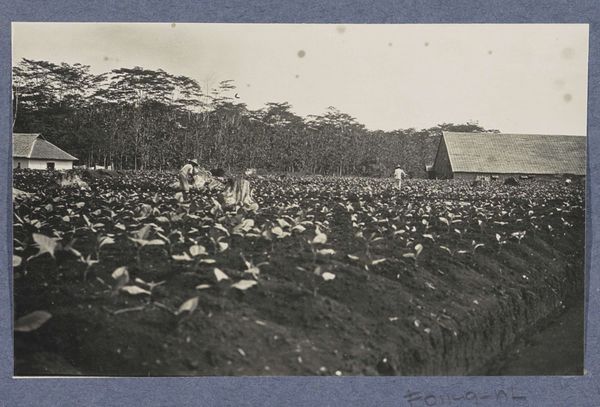

Tabaksveld op het Bindjey Estate van de Deli-Batavia Maatschappij op Sumatra (40 dagen na aanplant) c. 1900 - 1920

0:00

0:00

anonymous

Rijksmuseum

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

orientalism

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

realism

Dimensions: height 137 mm, width 192 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have a gelatin-silver print from somewhere between 1900 and 1920. The Rijksmuseum calls it "Tabaksveld op het Bindjey Estate van de Deli-Batavia Maatschappij op Sumatra (40 dagen na aanplant)," which Google tells me means “Tobacco field on the Bindjey Estate of the Deli-Batavia Company in Sumatra (40 days after planting).” It's quite striking, seeing this vast field. What grabs you about it? Curator: This image invites us to consider the very tangible realities of colonial enterprise. Forget the romantic orientalism that's tagged here, look instead at the grid, the repetitive labor implied by the rows and rows of tobacco. How were these plants cultivated, harvested, and processed? Editor: You’re right. I see those tiny figures in the field now, and the structures, presumably for drying the tobacco… I hadn’t considered the labor involved before. Curator: Exactly. The "anonymous" attribution also becomes significant. Who wasn't deemed important enough to be credited? Whose hands brought this commodity to market? What stories do these unnamed laborers hold? Editor: That flips my perspective completely. What seemed like a distant, historical landscape becomes much more immediate, almost visceral. It’s no longer just about looking at pretty scenery but understanding the socio-economic machine behind its production. Curator: And this process wasn’t abstract – it hinged on material conditions: soil, weather, the physical endurance of those workers. The photograph itself, as a mass-produced object, participates in this network of production and consumption. Do you see now how the image transcends merely being a 'landscape'? Editor: Yes! It's less about the scene and more about the system that created the scene. The medium itself—the photographic print—becomes implicated in the same system it depicts. Thanks for helping me look beneath the surface.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.