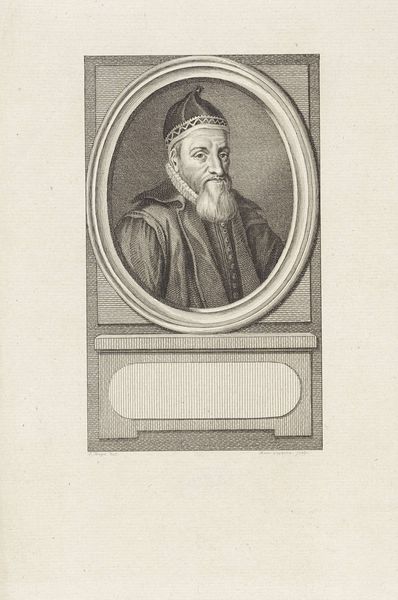

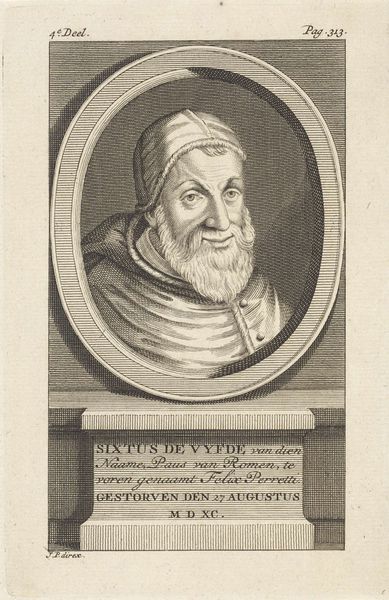

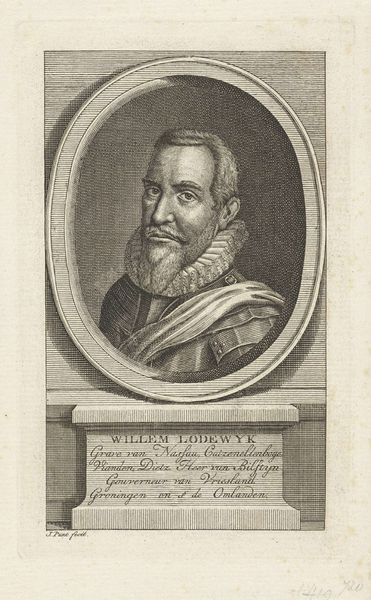

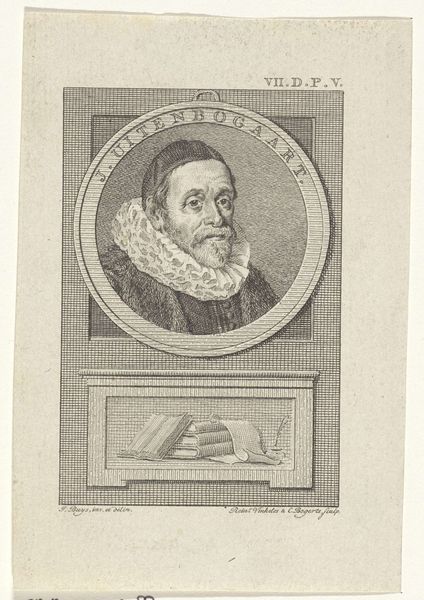

engraving

#

portrait

#

neoclacissism

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 152 mm, width 90 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Welcome. We are standing before "Portrait of Willem Eggert," an engraving from 1789 by Reinier Vinkeles, currently held at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: There's a quiet dignity to this engraving. The man’s face seems to carry the weight of contemplation, almost like he’s grappling with an important thought. It feels rather imposing despite the simple composition. Curator: Vinkeles, who had studied under Cornelis Ploos van Amstel, captured Eggert within the neoclassical artistic and cultural norms of the period. This was an era where civic virtue was idealized, and one's public role was a reflection of their moral character. Editor: I notice that, particularly how his attire—the head covering and scarf—subtly denotes a certain social status without ostentation. Do we know much about Eggert himself and how Vinkeles aimed to portray him within that societal context? Curator: Willem Eggert was indeed a prominent figure in Amsterdam, serving as a member of the city’s council. The artist consciously eschews the flamboyant styles and frivolous aesthetics to emphasize Eggert's gravity and service to the republic, reflecting Enlightenment values of reason and public service. Editor: It's fascinating how the medium of engraving, with its linear precision, reinforces the neoclassicist ideals. The even lighting and controlled detail add to the impression of rational clarity—but does this somehow sanitize the real, lived complexities of a powerful man? Does it do a disservice by not acknowledging a wider intersectional narrative about this historical figure? Curator: Indeed. The limitations of portraying a holistic representation in a formal portrait should not be ignored. These portraits served very specific purposes. The choice of medium was critical as well. Engravings such as this were often reproduced widely. They bolstered visibility of the portrayed and their contribution to public service in society at large. Editor: A strategic exercise in social engineering! Yet even within those constraints, the eyes hold a story, maybe of responsibility accepted or struggles endured. The image sparks debate around identity, visibility, and societal function. Curator: I agree; portraits such as this reflect how the Republic’s societal framework intertwined with moralistic perspectives during that time period. Editor: These insights open dialogues about power, representation, and what constitutes 'public good'—questions endlessly relevant to this day. Curator: Precisely, thank you.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.