#

abstract expressionism

#

abstract painting

#

rough brush stroke

#

fluid brush stroke

#

charcoal drawing

#

possibly oil pastel

#

fluid art

#

acrylic on canvas

#

underpainting

#

line

#

abstract art

Copyright: Public domain

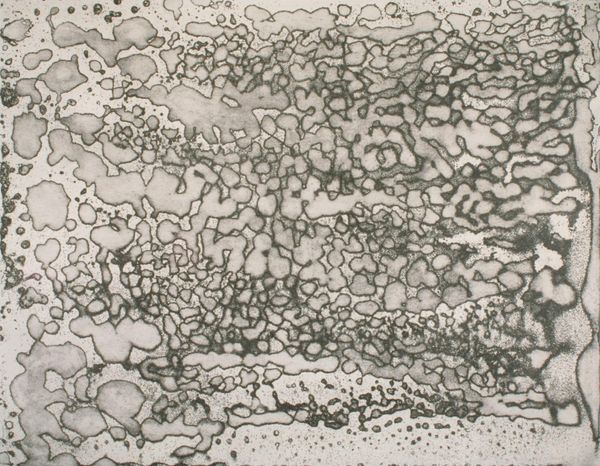

Curator: Welcome. Here we have John Ruskin’s “Moss and wild strawberry,” completed in 1872. Editor: It has a delicately haunting feel, doesn't it? Like peering into a shaded, forgotten corner of a forest floor. I'm drawn to the stark contrasts in texture and the subtle gradations of light. Curator: Ruskin was deeply invested in close observation of the natural world. His socio-political writing constantly referred back to these acute, empirical observations. Editor: Indeed, you can almost feel the texture of the moss under your fingertips just by looking at the drawing! It makes me think about the materials he used, probably graphite, perhaps some charcoal mixed in? And I’m curious, how readily were these materials available? Was this accessibility influencing the art being produced at the time? Curator: Excellent questions. Remember that Ruskin believed in the power of art to improve society, advocating for artistic training for working men and challenging the industrial exploitation of both people and natural resources. Editor: Yes, his efforts to bridge that divide are palpable here, as a close examination would require patience and appreciation of minute differences – qualities to be fostered through interaction with the image and then ideally, with the external world it seeks to depict. What about the presentation of his work? How were pieces like this exhibited and seen? Curator: Largely within the context of educational institutions. Ruskin was himself Slade Professor of Fine Art at Oxford. His works circulated as exemplars of observation, but also as polemical statements. Editor: And given his emphasis on the importance of manual labor, what kind of influence would you say his practice had on, say, art schools that came after? Or craft traditions and the blurring of fine art and artisanal work? Curator: Ruskin's aesthetic theories profoundly shaped the Arts and Crafts movement and beyond. He pushed for art that honored the worker, rejecting mass production for the integrity of handmade objects. This challenged the academic hierarchies of the art world, shifting attention toward design and decorative arts. Editor: It really feels as though you could just reach out and pluck a wild strawberry. Looking at this makes me want to get my own hands dirty— to feel the grit and the potential of turning a simple piece of graphite into an intimate vision of the world. Curator: I leave contemplating the interplay of observation, critique, and aspiration Ruskin presents, forever relevant to both art history and its ability to reflect human concerns.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.