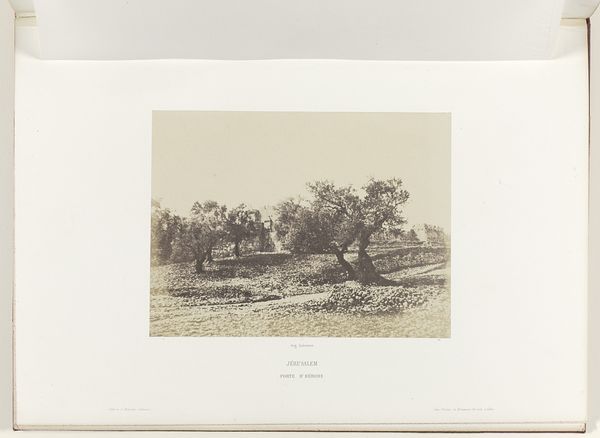

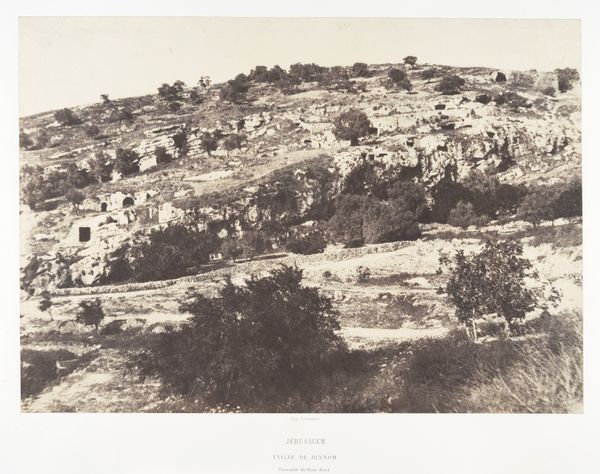

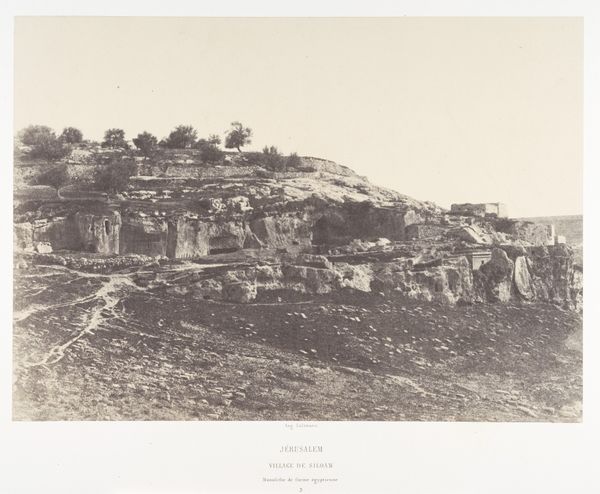

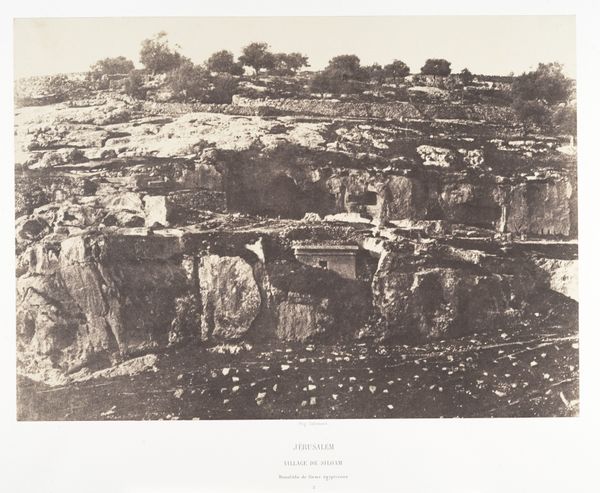

Dimensions: Image: 23.1 x 33 cm (9 1/8 x 13 in.) Mount: 44.8 x 60.3 cm (17 5/8 x 23 3/4 in.)

Copyright: Public Domain

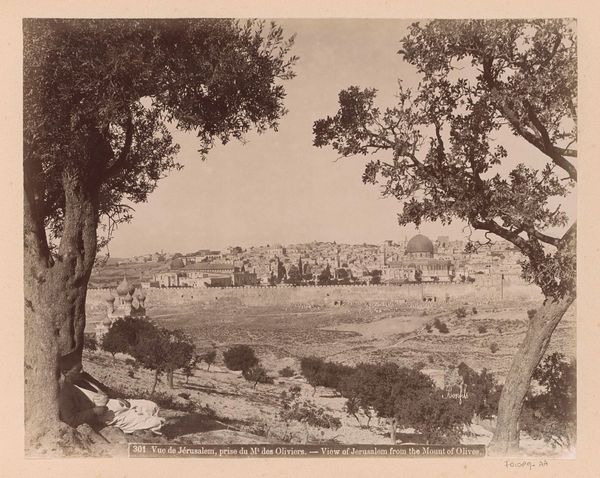

Editor: So, here we have Auguste Salzmann's "Jerusalem, Porte d'Hérode," a gelatin-silver print from around 1854-1859. It depicts a somewhat barren landscape with a city gate in the background. I find the starkness quite striking. What do you see in this piece? Curator: I see a deliberate construction of narrative steeped in 19th-century Orientalism and the politics of archaeological photography. Salzmann was commissioned, ostensibly, to document biblical sites, but his work is far from objective. It presents a particular view of Jerusalem, almost as a relic or a landscape awaiting reclamation. Editor: Reclamation by whom? Curator: That’s the crucial question. Think about the context: European powers were increasingly interested in the Middle East. Photography, at that time, was viewed as objective, scientific even. Salzmann's images, like this one, became tools in a broader colonial project, visually reinforcing European claims and interests. Editor: So it’s less about capturing the city as it *was*, and more about creating a narrative for a specific audience? Curator: Precisely. Consider the absence of people. It's a depopulated landscape, almost staged. The focus on ruins and barren land subtly implies a need for Western intervention and "civilization." And think about the orientalist aesthetic – it plays into stereotypes of a timeless, unchanging East, ripe for Western "improvement". How does that sit with you? Editor: It makes me rethink my initial impression of stark beauty. The “starkness” might actually be a carefully curated image designed to further a specific political agenda. I see now that art is never neutral. Curator: Exactly! By understanding the historical context and the power dynamics at play, we can begin to deconstruct these seemingly objective images and recognize the complex, and sometimes problematic, narratives they perpetuate. It challenges us to critically examine whose story is being told and for what purpose.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.