photography

#

portrait

#

photography

#

genre-painting

#

realism

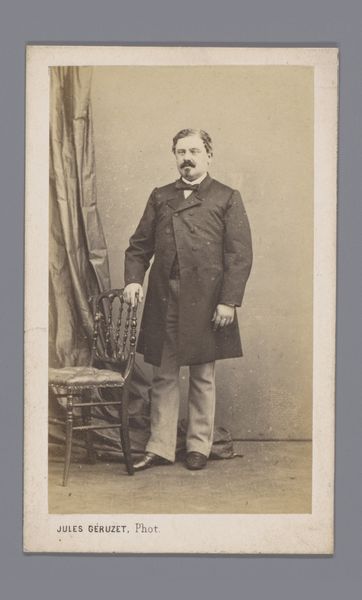

Dimensions: height 105 mm, width 61 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

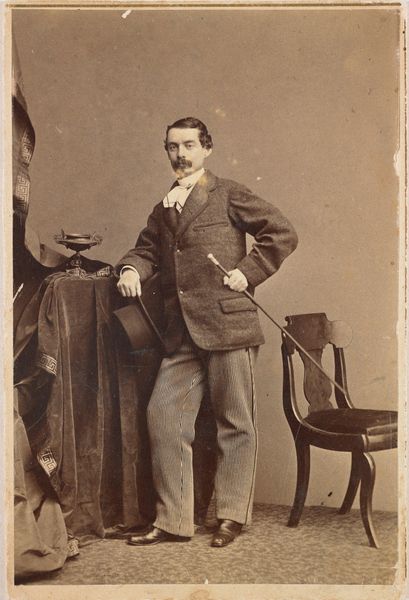

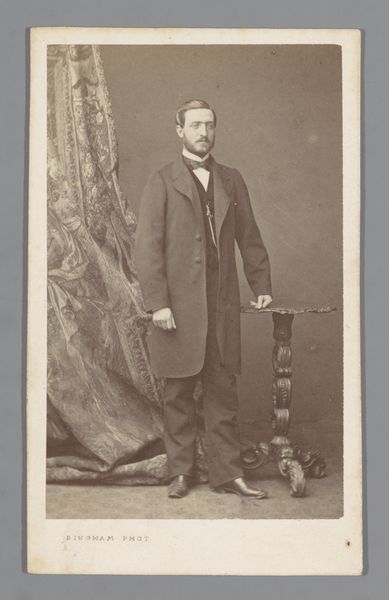

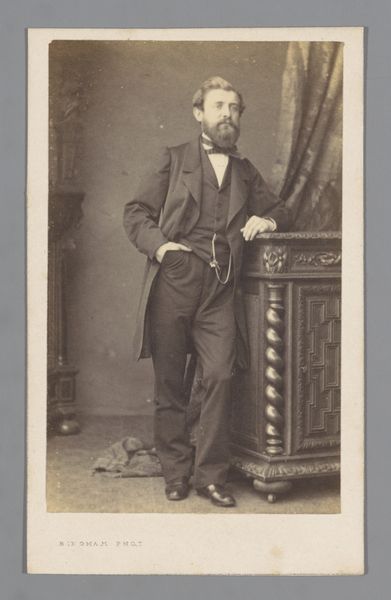

Curator: Isn't he handsome? This intriguing photographic portrait from the Rijksmuseum is called "Portret van een onbekende staande man," or "Portrait of an Unknown Standing Man," dating from 1867 to 1879, credited to Ferdinand Mulnier. Editor: Absolutely. There's a stoic grace in the composition, the way the light catches the line of his jaw. I’m curious about the implicit codes in a photo like this, a "carte de visite"—what performative power does such a portrait hold, in the construction of masculine identity? Curator: Ah, precisely. The controlled setting and the elegant yet somehow understated clothing suggests so much about his class. Did this realism actually convey an attainable aspiration? His is an air of middle class confidence, just as he seems ready for business. The almost throwaway placement of a chair hints at implied action or mobility, if only for an instant. And the placement of that oddly carved side table is quite deliberate. Editor: It's almost as if he's posing for posterity, embodying ideals of bourgeois virtue. Yet, within this formal structure, are glimmers of resistance. Those relaxed trousers; they defy convention and speak to shifting paradigms around male comportment during the late nineteenth century. What is Mulnier communicating by allowing a modicum of irreverence to surface? The walking stick too – for mobility or just as an accessory for aesthetic posturing? Curator: Interesting you call his outfit relaxed. Compared to much earlier styles, true, but consider the possibilities of photographic manipulation. This era saw enormous creative latitude; to my eye the final prints are meticulously posed – almost staged! Each visual component strategically places this figure between traditional gentility and aspirational realism. Mulnier understands this perfectly. Editor: Right. In any case, it makes one ponder the politics inherent in how appearances of the "bourgeois" are crafted. Whose expectations are being met in this encounter, if that can be parsed through all these sepia-toned years? The photograph’s existence—and then its display—speak volumes about visibility then and now. Curator: Yes, the portrait as an act, as much as it is art. Seeing this "unknown" through your interpretive lens has truly enriched the viewing. Editor: Thank you! I always learn new insights during these dialogues about power and perception.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.