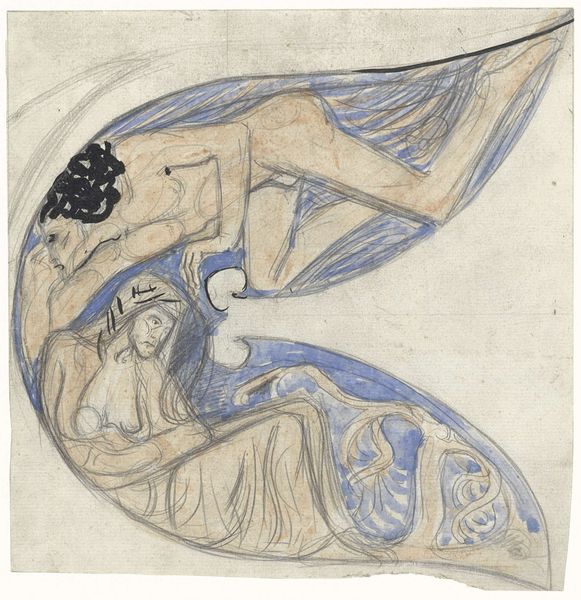

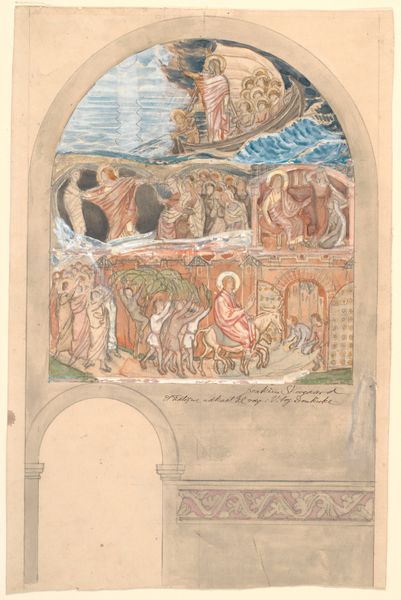

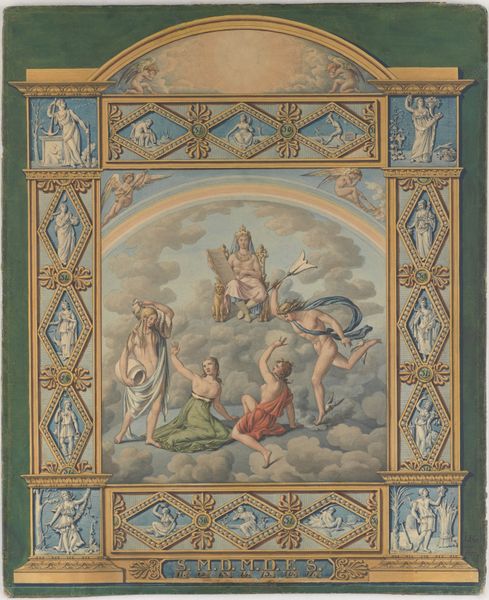

Sketch of the Mosaic Panel 'In the Name of Life' for the Interior of the Conference Hall of the Tambov Chemical Plant 1971

0:00

0:00

mixed-media, watercolor, mural

#

mixed-media

#

water colours

#

narrative-art

#

soviet-nonconformist-art

#

figuration

#

social-realism

#

watercolor

#

coloured pencil

#

mural

#

mixed media

#

watercolor

Copyright: Valerii Lamakh,Fair Use

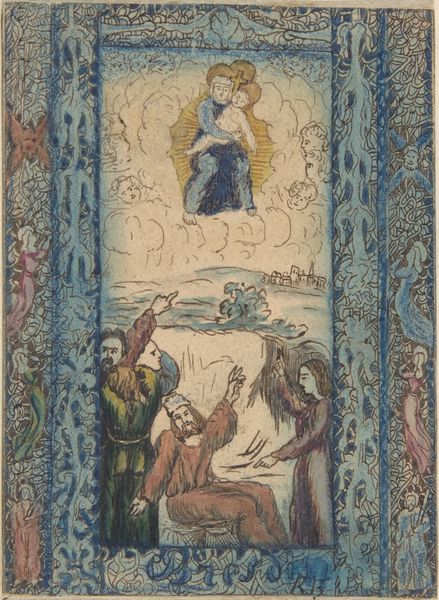

Curator: Here we have Valerii Lamakh's "Sketch of the Mosaic Panel 'In the Name of Life' for the Interior of the Conference Hall of the Tambov Chemical Plant," created in 1971. It’s a mixed-media work using watercolours and coloured pencil, intended as a study for a large mosaic mural. Editor: My initial impression is one of subdued optimism. The pastel blues and whites create a calming atmosphere, but the allegorical figures seem to strive towards something greater. The colour palette does somewhat neutralise any reading of resistance that is often aligned with this artist, in favour of something far more illustrative. Curator: Precisely. Lamakh worked during a time of strict state control over artistic expression, making him part of the Soviet Nonconformist Art movement. Social Realism was the official style, but artists often subverted or worked outside those boundaries. This mosaic sketch, meant for a chemical plant, embodies that tension between the idealised socialist vision and the realities of Soviet life. The female figures evoke classical muses, but are combined with images of industrial progress. Editor: So, these figures aren't just aesthetic choices but ideological ones as well. Can you say more about that? Curator: Absolutely. Consider the central figure holding the child aloft. She seems to represent the future, supported by industry, progress, scientific endeavour. The rainbow emerging from what looks like industrial towers symbolises the utopian promise. However, look closer. These figures aren't empowered autonomous individuals; they are passive, ethereal ideals almost empty of humanity or dynamism, reflecting a tension that, for me, represents an incomplete promise, perhaps also symbolic of the failed utopia. How, in fact, might women internalise an image of power such as this? Editor: I can certainly understand your interpretation from that lens. To me, it reflects on how public art was—and continues to be—used as a tool for social engineering. The placement in a chemical plant suggests an attempt to inspire workers, to connect their labour to a grand narrative of progress and human advancement, albeit from a place rooted in historical patriarchy, which seeks to reinforce an explicit set of power dynamics that serve its political agenda. Curator: The very muted tones in the sketch is what draws my attention; even for the mosaics themselves, one must take into consideration their accessibility, that is to say, which public, or publics, it might serve as it presents the face of both socialist hope, and artistic compliance. Editor: These visual narratives were a vital aspect of Soviet ideology. This panel isn't just a decoration; it is an articulation of national identity, a statement of values, and an argument for a certain way of life. Curator: Indeed. The context transforms it from a decorative piece into a powerful artifact of social and political history. Thank you, that gives me a whole new perspective on it. Editor: The pleasure is mine. Reflecting on this artwork has truly opened my eyes to how context is crucial in our reading and analysis of artistic intent.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.