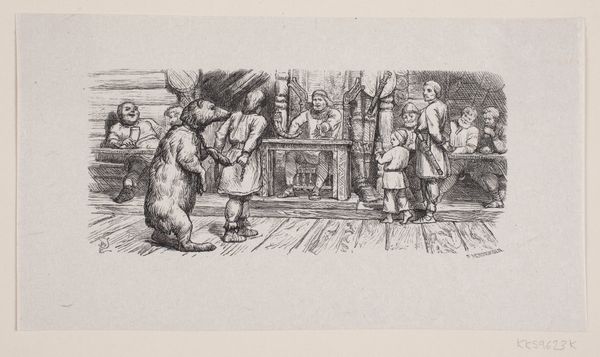

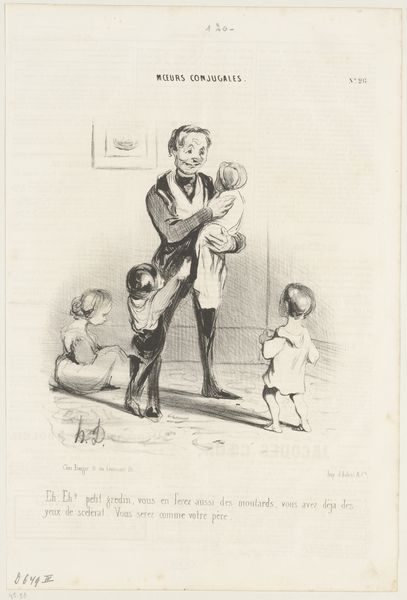

Illustration til "Halvhundrede Fabler for Børn" af Hey 1834

0:00

0:00

print, engraving

#

narrative-art

# print

#

romanticism

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: 107 mm (height) x 139 mm (width) (bladmaal)

Editor: Here we have Martinus Rørbye's "Illustration til 'Halvhundrede Fabler for Børn' af Hey," created in 1834. It appears to be an engraving, a print of some kind. I'm struck by the way the image depicts this street performer with his performing animal, engaging a group of children. It feels like a real glimpse into a moment in time, but what does it tell us about its context? Curator: It's fascinating how Rørbye captures this scene, isn't it? Beyond the immediate charm, we see a reflection of the Romantic era's fascination with both childhood innocence and the social realities of everyday life. How do you think the portrayal of street performers like this might have resonated with audiences in 1834? Editor: Well, on one hand, the kids seem to be enthralled and fascinated by the show. Maybe they saw some sense of entertainment in it. On the other hand, one might feel some pity for the person forced to make a living in this manner. Curator: Exactly. The public role of art during this time was to explore such sentiments. Consider how institutions and galleries were emerging as spaces for public discourse. Works like this facilitated a dialogue about class, entertainment, and the lived experiences of different societal groups. The very act of depicting this scene elevates it, prompting questions about value, worth, and visibility. What is the most striking feature about this piece that, perhaps unintentionally, suggests that this performance could only occur in an environment where social class differences are highly evident? Editor: It’s that contrast between the simple performance and the apparent curiosity of the children. It is indeed an eye-opener regarding societal disparities, presented in an understated fashion. Curator: Precisely. It's a subtle commentary on social structure. It reminds us that even seemingly simple images can be potent tools for understanding the public role of art and the political dimensions inherent in image-making. Editor: I see now. It really makes you wonder about all the other underlying meanings within the work. Thanks for clarifying this.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.