print, photography

#

kinetic-art

# print

#

photography

#

geometric

#

nude

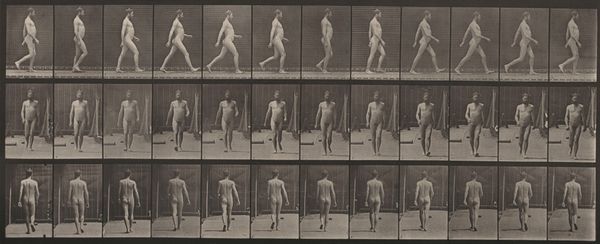

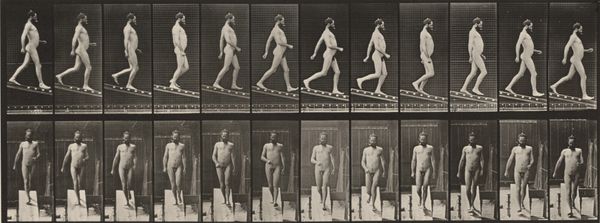

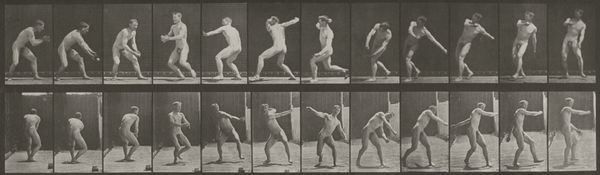

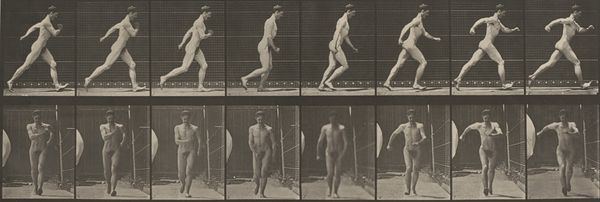

Dimensions: image: 18.9 × 38.7 cm (7 7/16 × 15 1/4 in.) sheet: 48 × 60.4 cm (18 7/8 × 23 3/4 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

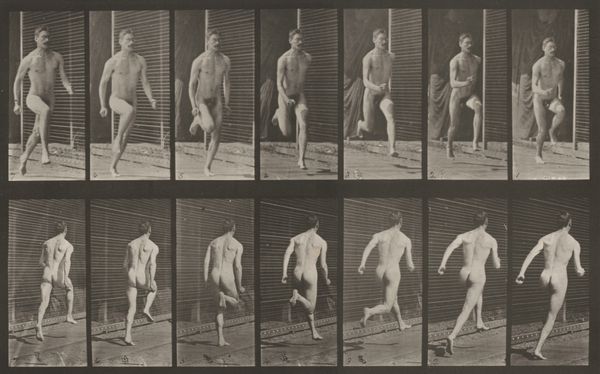

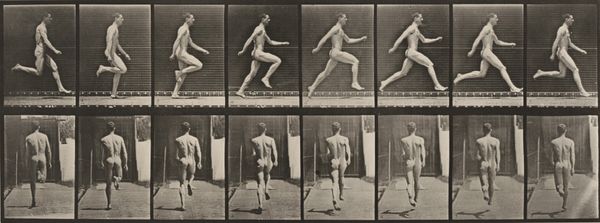

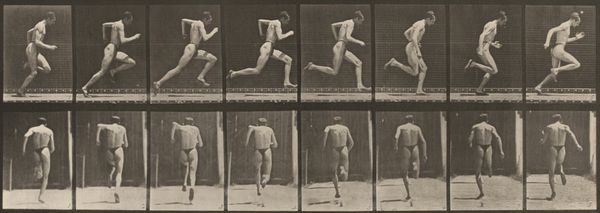

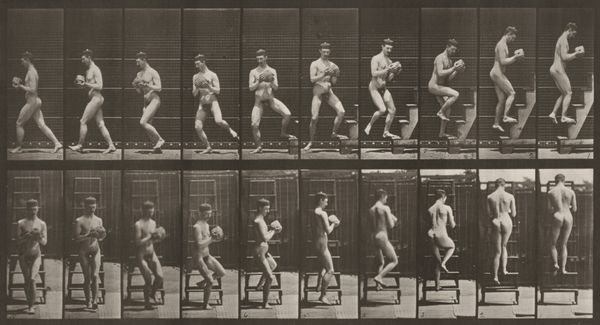

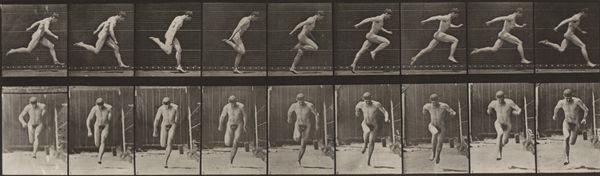

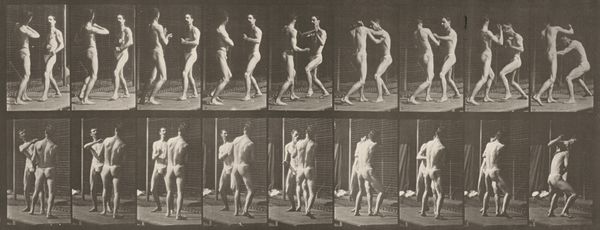

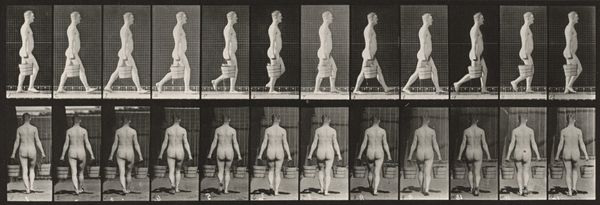

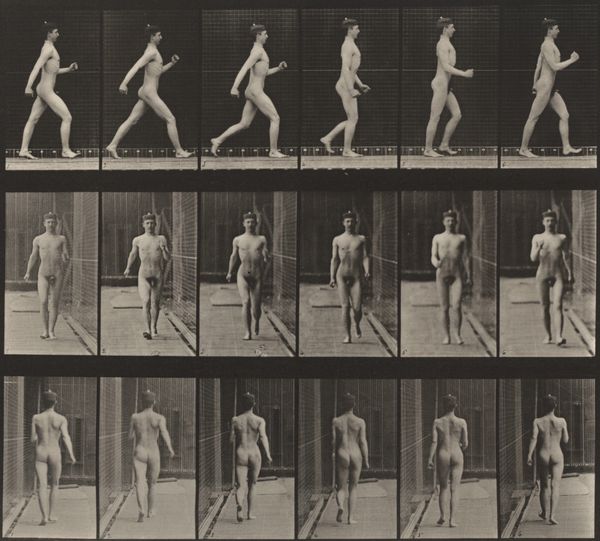

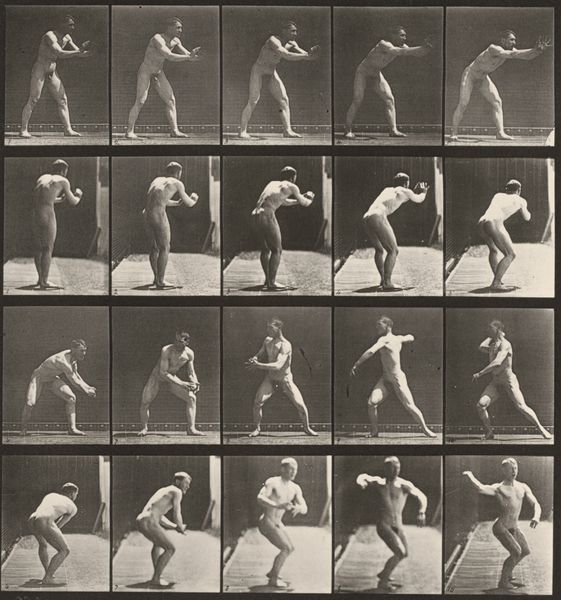

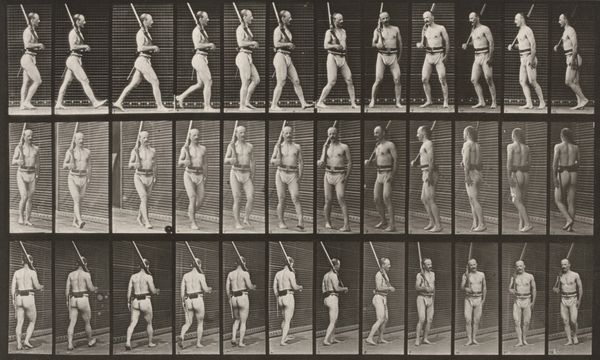

Curator: Let's take a look at Eadweard Muybridge's "Plate Number 3. Walking," a photographic print from 1887. What are your immediate thoughts? Editor: I’m struck by the stillness despite the subject, this near-palpable tension between frames attempting to liberate a body from the strictures of temporality. The light itself is almost geometric. Curator: Muybridge’s work was revolutionary in its time. He was commissioned to prove Leland Stanford's theory that a horse lifts all four hooves off the ground during a gallop. This particular image of a walking nude is part of his larger project "Animal Locomotion," an attempt to scientifically catalogue movement. Editor: The grid imposes a powerful structure. We're not just seeing a body in motion, but motion itself dissected, presented almost as data, an early form of what we now call kinetic art. There’s an unnerving seriality. Curator: Absolutely. And the context is fascinating. This project was driven by a wealthy industrialist with a vested interest in horse racing, pushing scientific inquiry. It's worth considering the cultural attitudes towards the body that allowed this to be framed as scientific rather than simply…voyeuristic. The absence of context except for the grid enhances this sense of "objective" observation. Editor: It’s difficult to ignore how that light falls on the muscles; he is rendered less of a person and more of a physical object for display. We tend to bring so much meaning to movement, yet Muybridge seems focused on reducing it to its simplest visual components. The uniformity contributes to this—a relentless objectivity, perhaps? Curator: Yes, the work raises profound questions about scientific authority, gender, and representation, not to mention art history's own fraught history with the male gaze. Editor: It’s almost chilling in its clinical presentation. And even today, after decades of moving images, I remain captivated by the mechanics behind Muybridge’s exploration of motion. Curator: It is certainly a work that stays with you, challenging our assumptions about art and its role in both reflecting and shaping societal views. Editor: Precisely, a captivating glimpse at art and movement itself, broken down into increments, a meditation on something far beyond our static sightline.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.