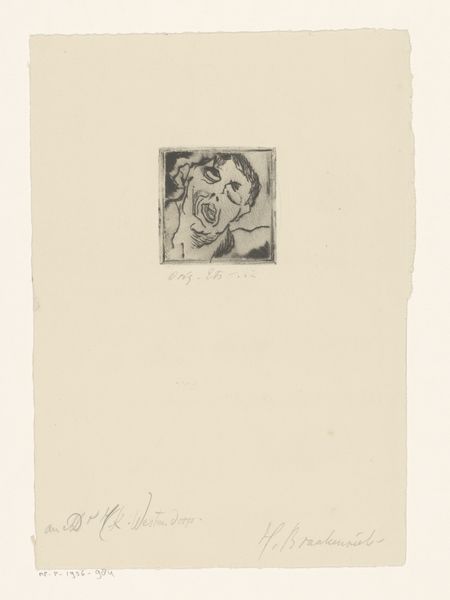

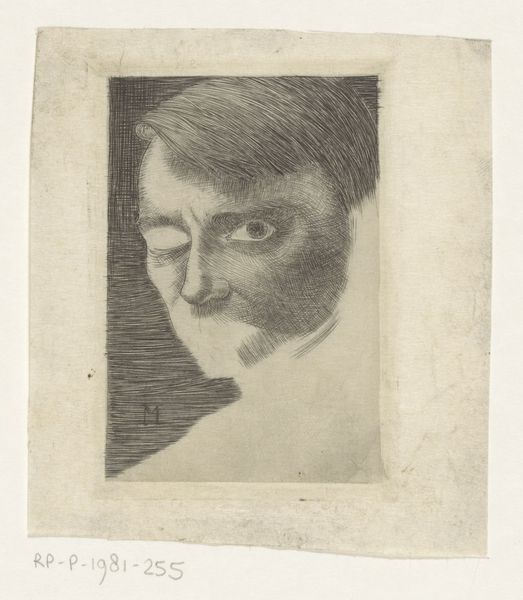

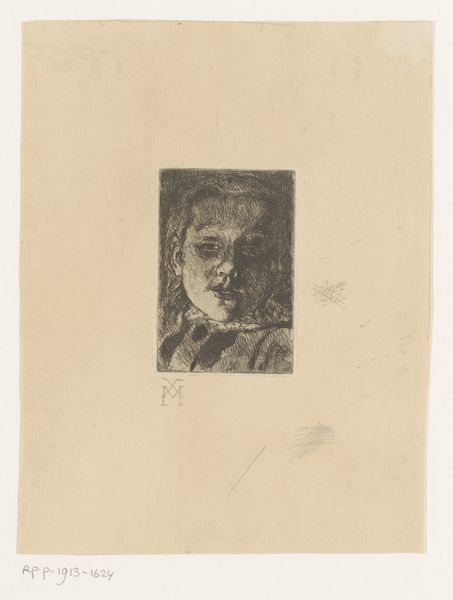

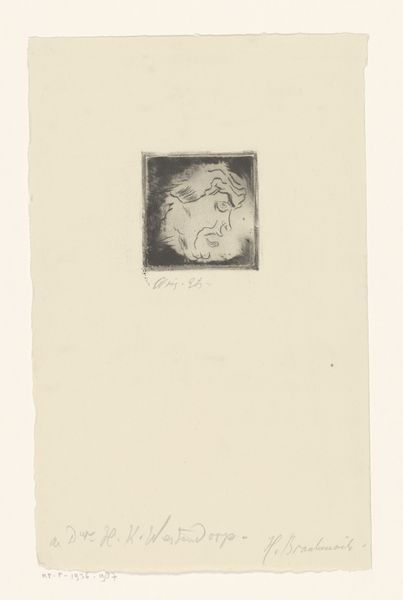

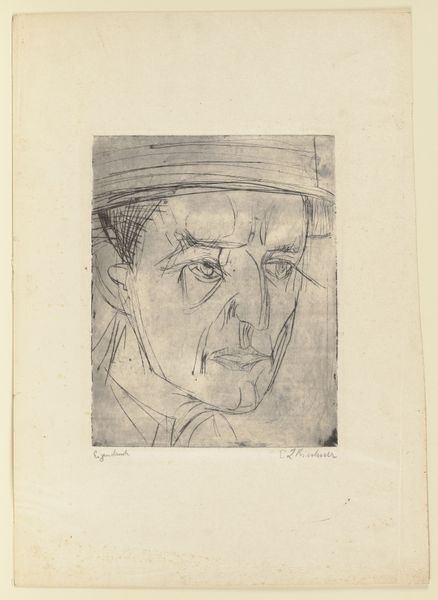

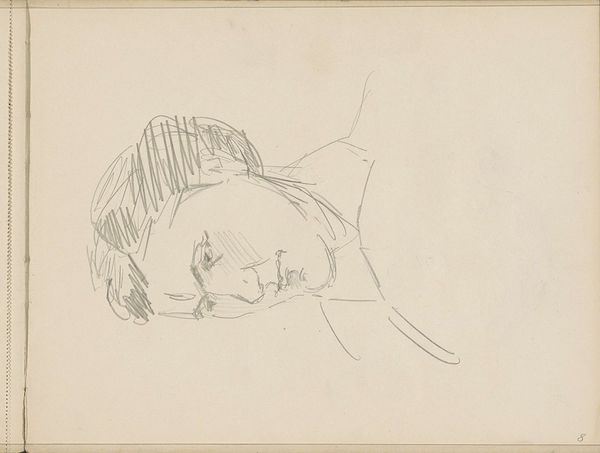

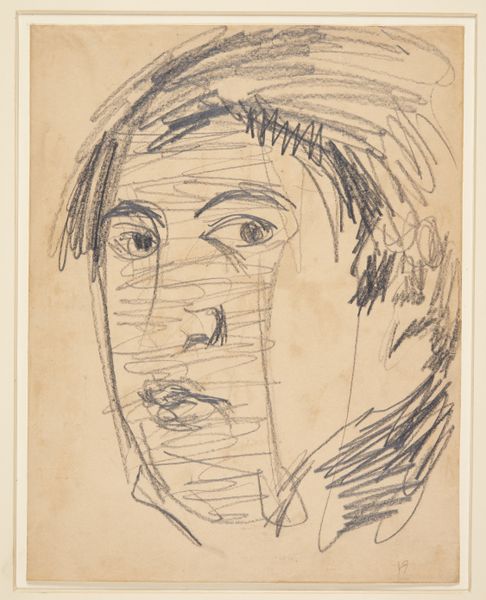

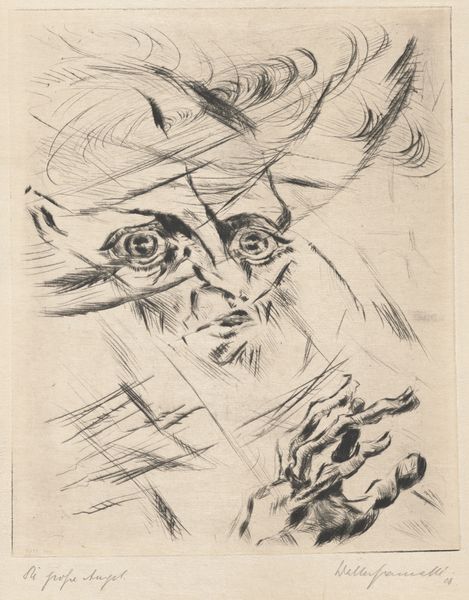

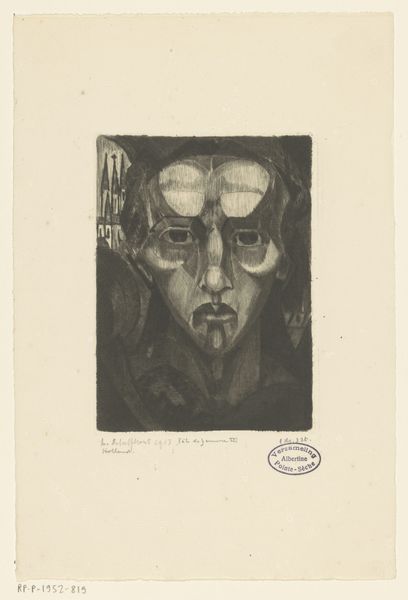

drawing, print, pencil

#

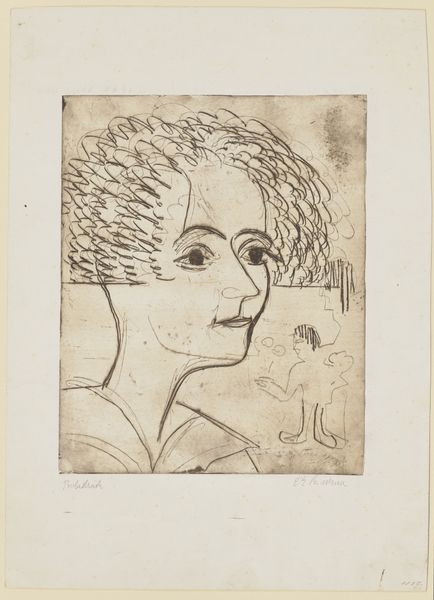

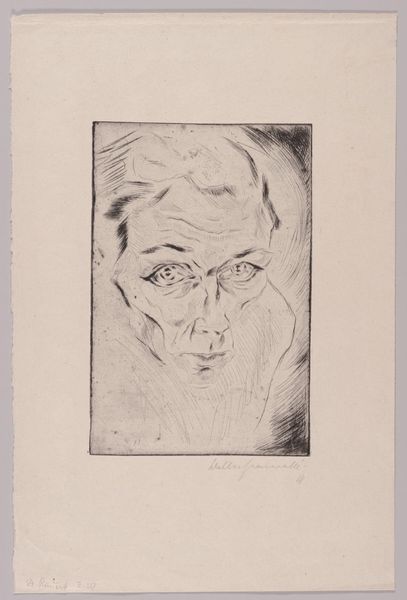

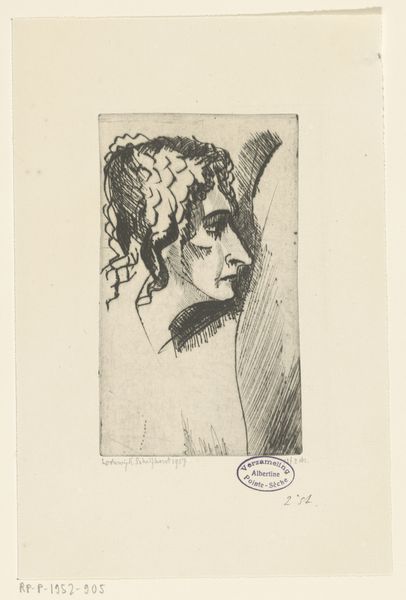

portrait

#

drawing

# print

#

pencil sketch

#

figuration

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

realism

#

monochrome

Dimensions: image: 75 x 91 mm sheet: 186 x 164 mm mount: 279 x 216 mm

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Editor: Here we have Thomas Yamamoto’s "Untitled (Head of a Sleeping Man)," created in 1946 using pencil as a print. I am really drawn to how raw and intimate it feels, like we're intruding on a very private moment. What strikes you when you look at this work? Curator: Well, for me, the post-war context is crucial. In 1946, societies were grappling with the aftermath of immense trauma and upheaval. How do institutions of art respond? Realism becomes newly fraught, charged with bearing witness. Consider Yamamoto's choice of subject: not a heroic figure, but a man asleep, vulnerable. Does this image offer a form of silent protest? Is the seeming intimacy less an embrace of sentimentality and more an indictment of an entire system? Editor: That’s a compelling point! I was thinking of vulnerability in a personal sense, but the wider societal implications are fascinating. Curator: The style reinforces this idea too. It’s a print but the drawing technique feels immediate. It is "realist", and yet has a nervous energy and an abstracted setting. Who gets to speak in realism? What’s the relationship between realism and truth, and how has the history of prints affected that perception? Are there any institutions in Yamamoto's past that would answer those questions? Editor: I see what you mean. It's not just a portrait of someone sleeping, it’s making a statement about power and representation. It makes you consider the silent sufferers and their place in a war-torn world. Curator: Exactly! By choosing this subject and treating it in this way, Yamamoto perhaps prompts us to question the grand narratives and acknowledge the quiet struggles, reshaping who we imagine to be relevant in this historic moment. It's about re-evaluating the power dynamics embedded within portraiture itself, who commissions them, and why. Editor: I never thought about portraiture having those power dynamics! Now I understand how it fits within that post-war struggle and questions its established structures. Thanks, this really changed my perspective. Curator: My pleasure! I am always grateful for another way to think about how we frame art with new dialogues.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.