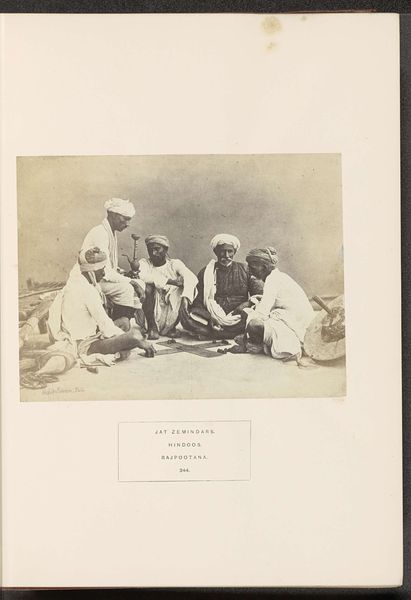

Portret van drie edelmannen of aristocraten van Jat afkomst met een bediende before 1874

0:00

0:00

photography

#

african-art

#

photography

#

group-portraits

#

orientalism

Dimensions: height 144 mm, width 168 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

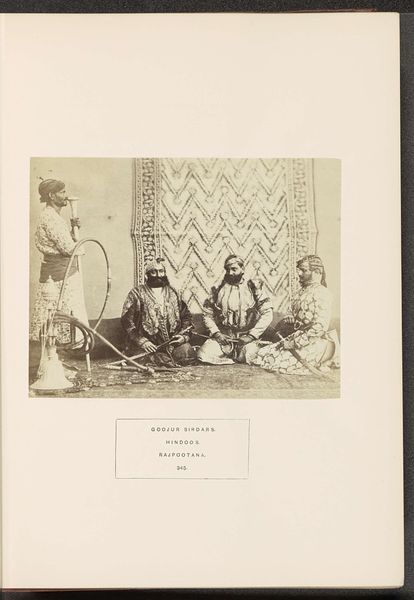

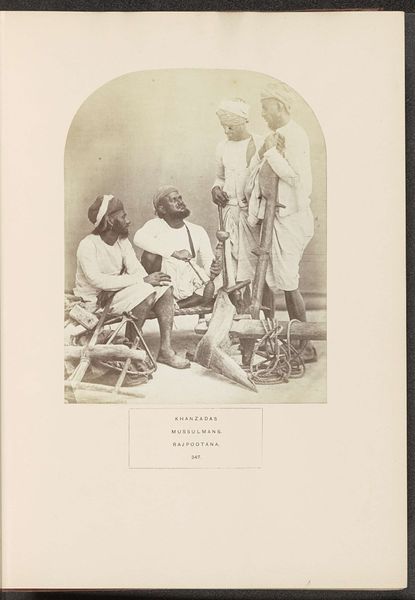

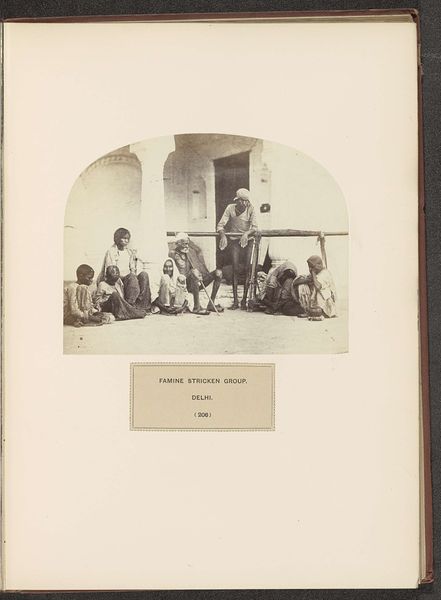

Curator: Before us is a photograph, dating to before 1874, made by the studio of Shepherd & Robertson. It's titled "Portret van drie edelmannen of aristocraten van Jat afkomst met een bediende," or "Portrait of three noblemen or aristocrats of Jat descent with a servant." Editor: The tonal range is exquisite, almost like looking at a meticulously rendered charcoal drawing. It conveys a palpable sense of staged formality, and yet I wonder what materials would have been accessible to someone capturing this likeness at the time. Curator: Well, the key material here is the photographic emulsion on the paper support itself. It would be fascinating to analyze its composition, tracing the origins of the chemicals, glass plates, and printing papers employed. Each choice, born of colonial trade routes and Victorian-era chemistry, influenced the final product. And don’t forget the studio props themselves – that backdrop! Its materiality, I bet, signaled specific aspirations. Editor: Indeed. It really speaks to how photography during this period, and specifically this kind of Orientalist portraiture, served very particular social and political purposes. Note how the sitters’ clothing is carefully displayed, almost cataloged, pointing towards an understanding—or rather, the imposition of an understanding—of Indian social strata by the British colonizers. This wasn't simply about documenting reality; it was about framing and constructing it. Curator: Exactly. And thinking about the photographer’s studio… it was very likely a nexus of exchange, where local labor intersected with colonial capital. It's critical to ask what their production and distribution networks reveal about empire and global trade at the time. The servant, posed rigidly at the back—his social position rendered explicit in the photograph. Editor: A chilling observation. The composition is deliberate and stark, emphasizing disparities in status, yet offering these men a presence and legacy in ways unavailable outside of these imposed systems. Photography democratizes visibility while potentially deepening already present divides. Curator: By dissecting its manufacture, its materiality and use, we uncover not just an aesthetic object but also a web of social relationships frozen in time. What at first seemed a straightforward portrait reveals itself as a material index of colonial dynamics and technological processes. Editor: And looking through a critical lens, we might remember that portraits, seemingly capturing truths, also participate in very complex narratives of identity and power, framed—quite literally—by historical conditions and social prerogatives.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.