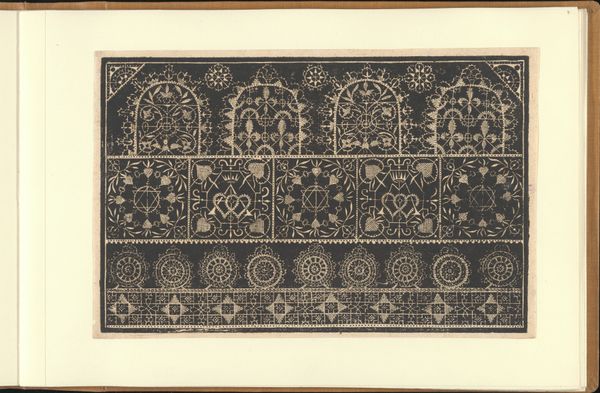

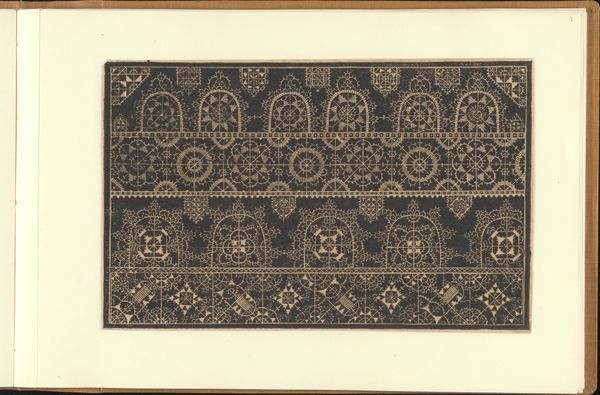

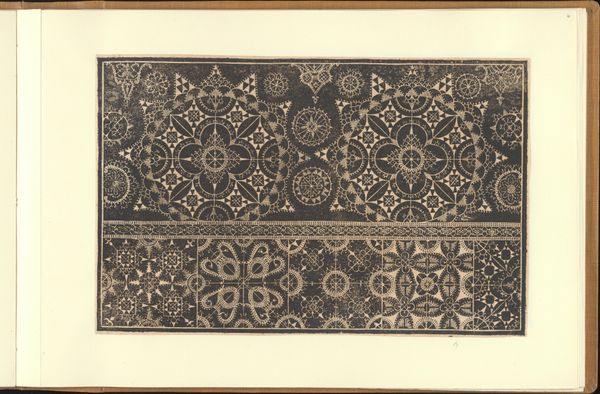

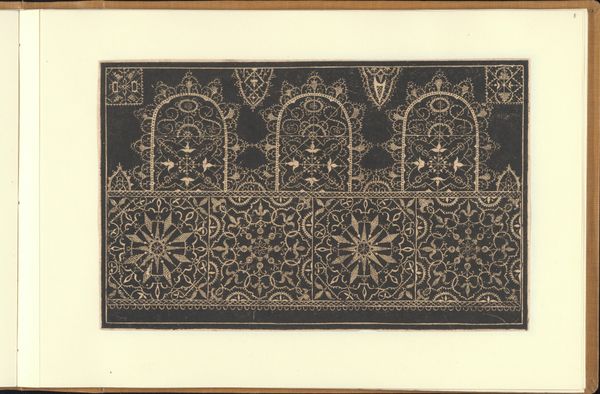

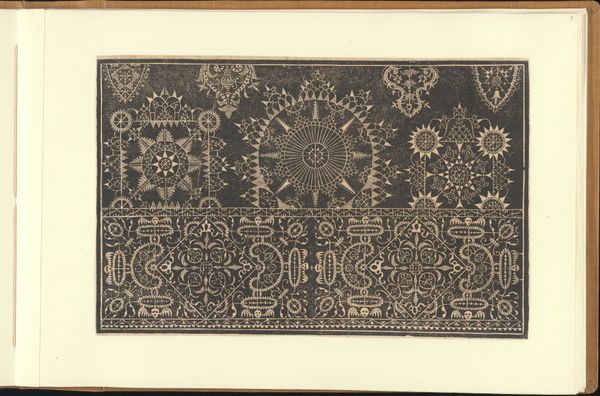

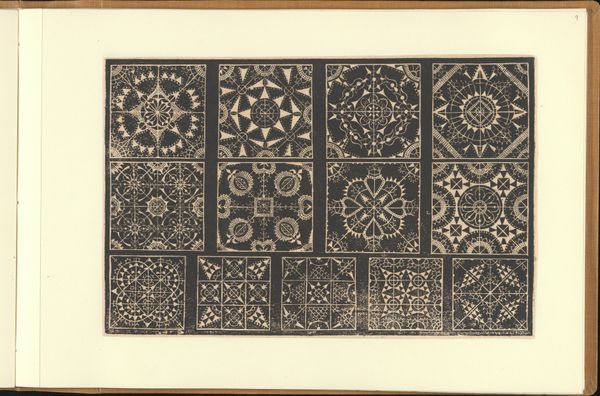

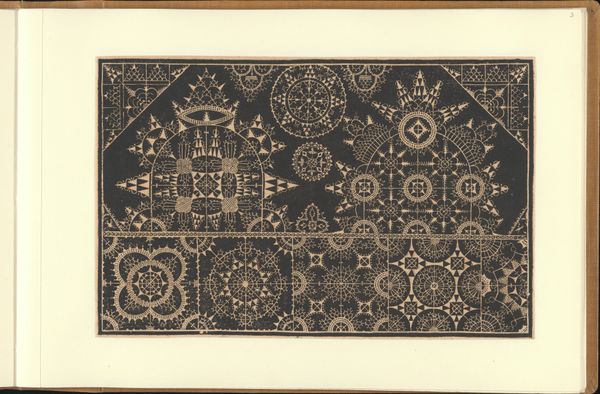

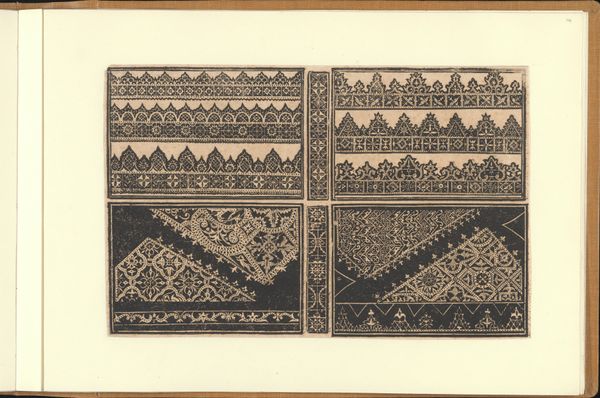

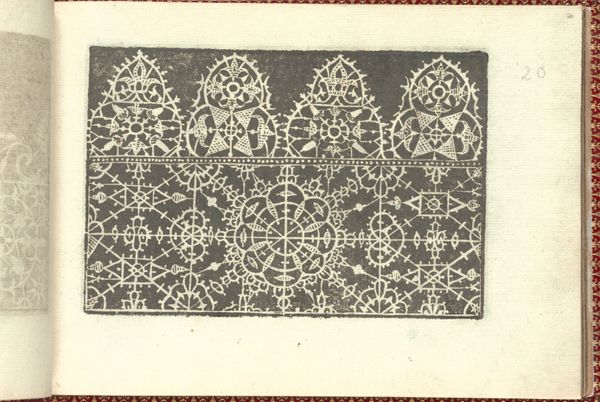

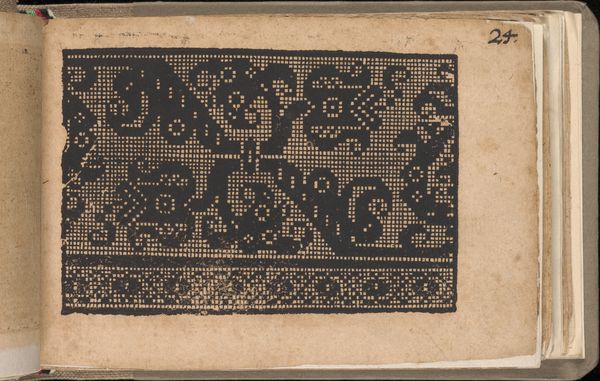

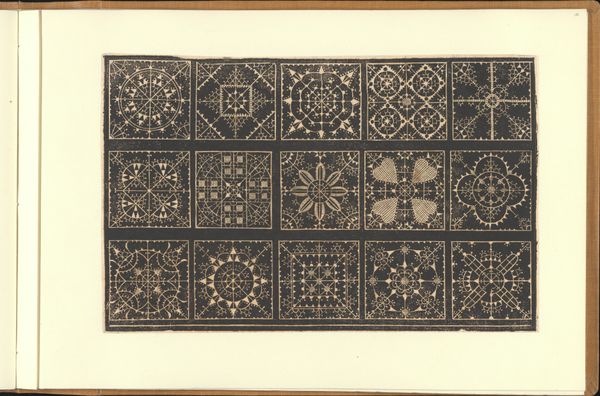

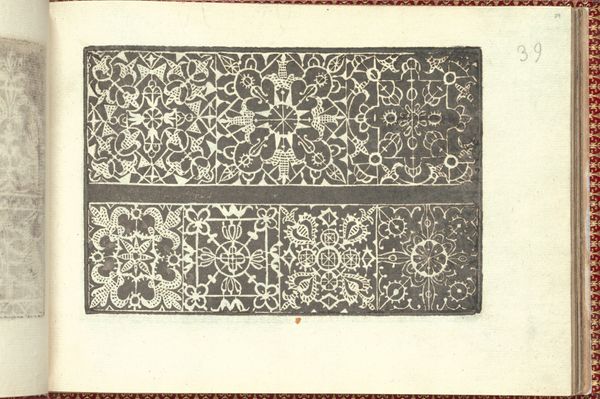

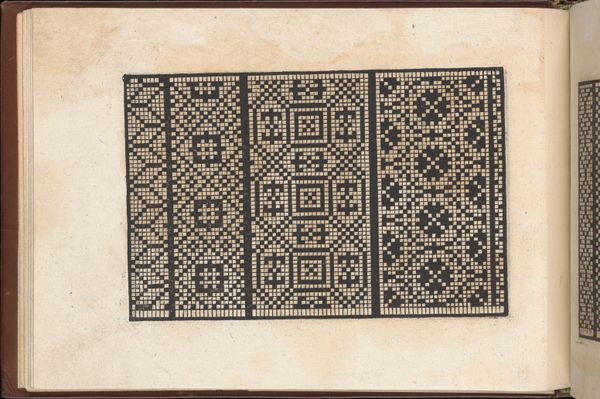

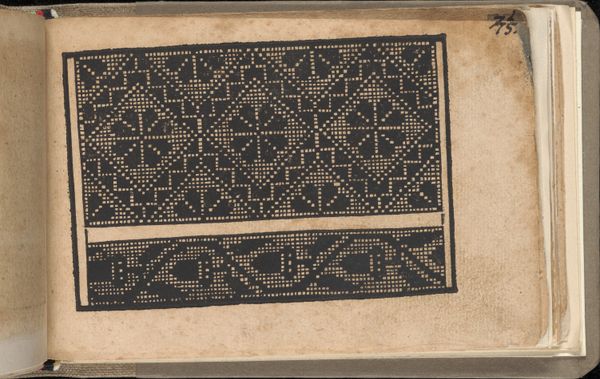

print, woodcut

# print

#

woodcut effect

#

linocut print

#

geometric

#

woodcut

#

decorative-art

Dimensions: plate: 6 7/8 x 10 1/2 in. (17.5 x 26.7 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This geometric artwork is titled "Schon newes Modelbuch...Page 2(r)," dating back to 1617. It resides here at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. What’s your first impression? Editor: Immediately, I'm struck by its density and intricacy. The way the light plays across the varying depths of the cut is wonderful. It feels simultaneously archaic and remarkably modern in its rigid, repeating design. Curator: It’s a fascinating piece, and context is crucial here. The artist was Sigismundus Latomus and this artwork consists of woodcuts and possibly other kinds of prints or drawings as mediums; keep in mind the role pattern books played in the rise of textile manufacturing. These designs were disseminated to workshops, influencing countless woven and embroidered goods. Editor: Exactly! Thinking about the composition in terms of structuralism, we see a clear articulation of horizontal registers—layers—each presenting a unique motif, but bound by an underlying formal language of symmetry. The variations feel like calculated deviations from a core principle. Curator: Absolutely. Consider the labor involved in creating the original woodblocks. This wasn't just about aesthetics; it was about providing functional designs accessible for reproduction and circulation across diverse European artisanal networks. What kind of consumer would use it, and for what products? That shapes how it was crafted. Editor: But it transcends pure utility. Look at the detailed, almost hypnotic arrangement of circular and rectilinear shapes. This appeals directly to our innate human desire for order, logic, even mathematical perfection. Curator: True, and the means of production—the relative ease of reproducing a woodcut—democratized design and the accessibility to all levels of artisanal shops. The very materiality—wood, ink, paper—speaks volumes about pre-industrial craft practices. Editor: This image uses repetition with subtle variance and provides a sense of both groundedness and progression. What seems so interesting here is not solely the intention of a utilitarian object for early manufacturers of textile, but the visual richness the work evokes in the eye of its beholder, an objective end of the design that enhances experience for maker and consumer. Curator: A fitting final observation, capturing the practical function married with a pleasing visual expression so characteristic of 17th-century design books. Editor: Indeed, something in this work that keeps me questioning our historical conception of high and low art forms in textile manufacture!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.