drawing, pencil

drawing

pencil sketch

charcoal drawing

figuration

pencil drawing

pencil

surrealism

portrait drawing

history-painting

northern-renaissance

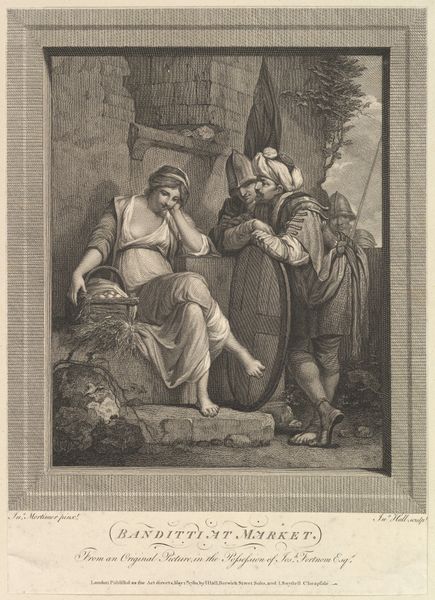

Dimensions: height 235 mm, width 179 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This pencil drawing, currently housed here at the Rijksmuseum, is entitled "Lot and One of his Daughters" by Jan Swart van Groningen, dating from 1530 to 1535. Editor: Initially, I am struck by the contrasting textures. Look at the smooth skin of the daughter versus the gnarled bark of the tree, all rendered in the limited tonal range of pencil. There's a powerful simplicity in the composition. Curator: Yes, and those contrasting textures amplify the figures’ symbolic meanings. Jan Swart is drawing upon a story freighted with symbolic weight. The daughter's relative youth and exposed skin contrast sharply with Lot’s patriarchal beard and concerned gesture, as he proffers the plate. Do you pick up any possible inferences of incest? Editor: The plate does lend itself to speculation about its contents and, indeed, it might imply that he’s holding a vial filled with the beverage to lower his awareness. I observe, however, the expert application of hatching and cross-hatching which delineates the rounded form of his arm. And is that a turban to the side of his feet? Curator: The turban functions as an emblem. We should remember the historical context. Lot’s narrative was very much about rejecting eastern corruption in favour of covenant and custom. His family needed refuge. So that turban on the floor implies those themes were prevalent during the Northern Renaissance. Editor: Interesting that you point to historical interpretation, as structurally, the piece does evoke an implicit dichotomy. It also seems there is very little interplay, however. She, after all, has bare feet and her garment and headdress indicate she already anticipates corruption and incestuous behaviors. Curator: The positioning of her hand on her dress indeed suggests acquiescence, perhaps resignation. The story and Jan Swart’s drawing are grim reminders that sacred beliefs can get warped by patriarchal corruption. Editor: But that rendering in pencil also means it's mutable. It suggests it can easily be rubbed out and started afresh—a narrative constantly rewritten and reinterpreted. The artist shows it could just all be imagination, sketched and ephemeral. Curator: Exactly. And like memory, always incomplete, partial, and interpreted. The brilliance here, is that Jan Swart gives us everything but asks us to bring our own convictions to the act of viewing, of meaning-making.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.