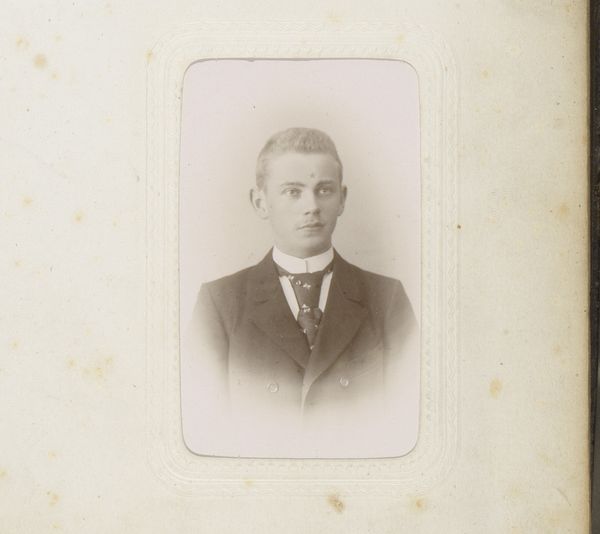

photography

#

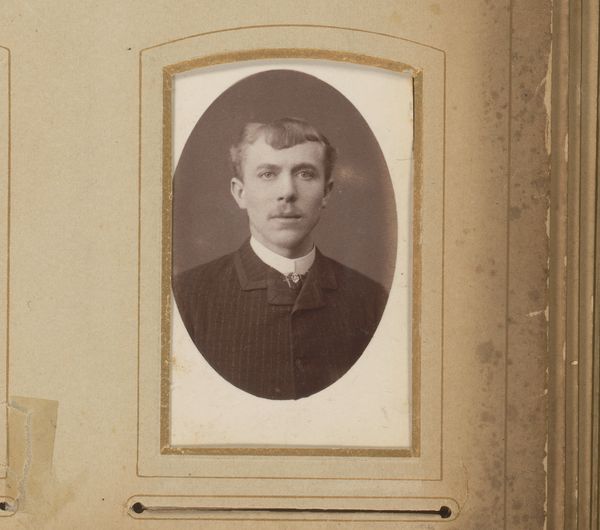

portrait

#

charcoal drawing

#

photography

#

oil painting

#

genre-painting

#

watercolor

Dimensions: height 85 mm, width 51 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have a curious piece: a photograph dating back to somewhere between 1850 and 1900. The sitter is described as "Portret van een jonge man, aangeduid als Gustav Schader," attributed to Carl Bräunlich. Editor: The frame is everything here! It feels like walking into a forgotten greenhouse, those illustrated vines creeping in around this young man. A feeling of faded beauty, or maybe faded privilege, too? Curator: Definitely a sense of time suspended. The young man is looking directly out at us with quite a serious gaze for what must have been a momentous and somewhat costly sitting. I wonder about his life… and why *this* was considered a vital image to preserve. Editor: Well, formal portraiture in that era, especially photographic portraiture, often reinforced social hierarchies. Looking at his attire, he certainly belongs to a specific class. The photograph becomes a signifier, declaring his position in society and reinforcing certain cultural expectations of masculinity and decorum. And that flowered border really softens him somehow… a sort of gilded cage? Curator: Gilded cage is interesting… although I can't quite shake this other feeling. Perhaps this photo was an effort at sentimentalising… think of lockets with a strand of hair of the beloved, perhaps that is too simplistic. There’s this slight sepia tinge... giving it that ghostly sheen. I’d venture that Bräunlich used lighting and printing techniques to suggest the past—a longing or melancholia. Editor: I agree the technical mastery is subtle, yet crucial. Early photography struggled to capture true color and depth. So that sepia… maybe it isn’t only about sentimentality but an attempt to overcome the limitations of the medium itself. Also the setting. To put a sitter, and the photo, back into nature by placing a frame with such evocative and well-drawn images really highlights an aesthetic bent to classical ideas of representation. Curator: It’s so easy to slip into armchair sociology. Who was Carl Bräunlich? Did he ever envision his work would have our prying eyes and interpretations centuries later? I hope young Gustav would be pleased to know that his likeness continues to provoke thought. Editor: And hopefully, it encourages more questions. How were visual economies functioning within families, communities, institutions? Photos are never neutral documents! They embody histories, anxieties, power dynamics... but also hopes. And, yes…the hope, I'm sure, to be remembered.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.