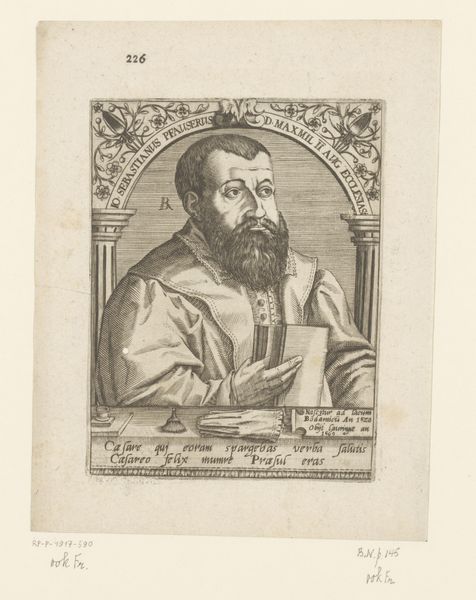

engraving

#

portrait

#

book

#

old engraving style

#

caricature

#

11_renaissance

#

portrait reference

#

pencil drawing

#

portrait drawing

#

history-painting

#

northern-renaissance

#

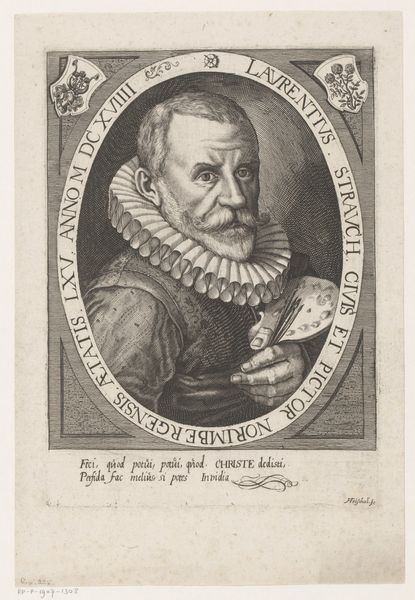

engraving

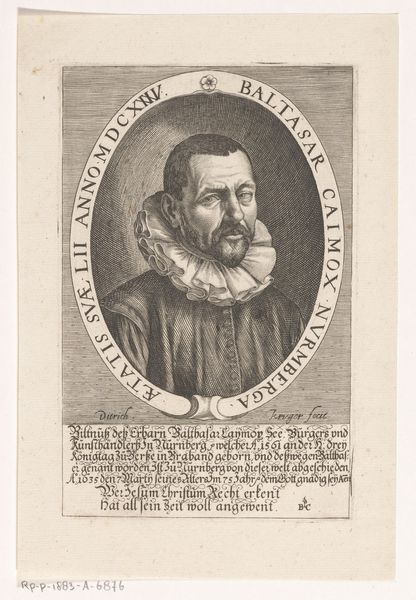

Dimensions: height 136 mm, width 104 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have "Portret van Wilhelm Xylander" by Robert Boissard, created somewhere between 1597 and 1599. It's an engraving, currently residing in the Rijksmuseum. The intricate lines, the way they create depth, are truly remarkable, and indicative of a skilled artisan at work. Editor: The poor man looks terribly severe! A world-weariness etched into every line, quite at odds with the elaborate flourishes that frame his portrait. It’s like trapping a melancholic soul in a gilded cage, don’t you think? Curator: I wouldn't go that far. The ornamentation serves a purpose. It's not mere decoration. The choice of engraving as a medium reflects the era's print culture and dissemination of knowledge. Prints allowed images and texts to circulate widely, promoting humanist ideas. Wilhelm Xylander, depicted here with a book suggesting scholarship, was himself part of that movement. Editor: Perhaps, but it also feels like an attempt to elevate him, to cast him in a light that seems almost... forced? Look at his eyes, the set of his jaw—he seems weighed down by the gravity of it all. Maybe that's what genius feels like? Curator: Maybe. Let's also consider the social context of portraiture at the time. Portraits functioned as status symbols, and their proliferation was intertwined with emerging notions of the individual. The engraving technique, by its very nature, involves a reproductive process; prints were often copied and disseminated, shaping Xylander's posthumous image. Editor: True. But there's an undeniable vulnerability, or perhaps honesty, captured here. It is more than mere replication; the portrait engraver managed to suggest interiority using only light, shadow, and line. Curator: And the level of detail… his ruffled collar, the subtle rendering of light on his face. Each element represents hours of labor, each a calculated decision intended to reflect not just his appearance, but also his standing. Editor: Agreed. It leaves me feeling both awed by the artistry and a bit saddened for Xylander. All those thoughts bottled up… but aren't we all, in our own way, just engravings of our former selves? Curator: Well, perhaps. Seeing how art embodies layers of production certainly deepens our understanding, wouldn’t you agree? Editor: Absolutely, but I'll keep a bit of mystery in my heart for Wilhelm. He looked interesting.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.