drawing, pencil, graphite

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

pencil drawing

#

romanticism

#

pencil

#

graphite

#

portrait drawing

#

realism

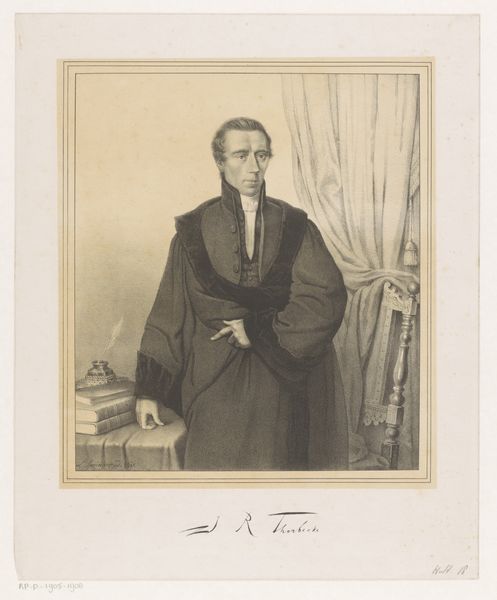

Dimensions: height 235 mm, width 155 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

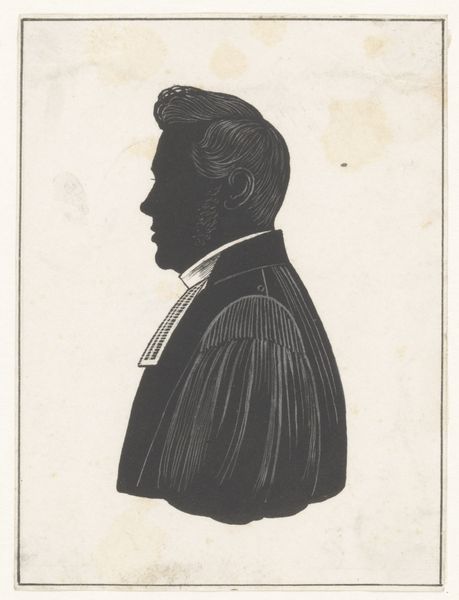

Curator: This pencil drawing, housed right here at the Rijksmuseum, is a portrait of Jan Rudolf Thorbecke by Carel Christiaan Antony Last. It's believed to have been made between 1842 and 1853. Editor: My first impression is of a man radiating thoughtful composure, almost severity, enhanced by the monochromatic palette. There's a strong sense of authority conveyed in this medium, oddly enough. Curator: I think it's the deliberate use of shadow and the meticulous detail that lends that gravitas. Last, while seemingly adhering to the aesthetic conventions of portraiture in his era, subtly infuses a sense of progressive liberalism into Thorbecke’s depiction. Editor: In what way? Is it his posture, the slight smirk that betrays a rebellious glint in his eyes or how can you detect hints of social reforms within its artistic DNA? Curator: Exactly. Consider the rise of bourgeois society and the growing emphasis on individualism during the 19th century. The portrait, in its ability to capture not just the likeness but the *character* of an individual, became a potent tool for solidifying social standing and propagating certain ideals. Think how Thorbecke’s expression hints at inner strength but also a willingness to engage. Editor: True, there's definitely an aura of purpose there. Yet, isn't there an element of romantic idealization here? It's interesting to see how social realism and romanticism intersect, especially in the political realm. Curator: Without a doubt. The artist is navigating that intersection, carefully constructing an image that speaks to the aspirations of a changing society. Notice his hand, gently posed, as if paused mid-speech. The drawing anticipates and helps construct Thorbecke's future legacy. The portrait then, performs crucial work, turning an individual into an idea. Editor: I think exploring portraits such as these beyond mere aesthetics allows for richer interpretation of what a political or social message means to the public then and even how we, today, assign new value to it based on intersectionality, whether it's of class or some other identifier. Curator: Absolutely. These pieces invite a layered analysis, linking social trends, personal narratives, and artistic representation to the broader discourse of history and how it’s actively shaped. Editor: It definitely shifted my first impression, reminding me of the power dynamics embedded within something as simple as a portrait and to what ends the final image is intended.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.