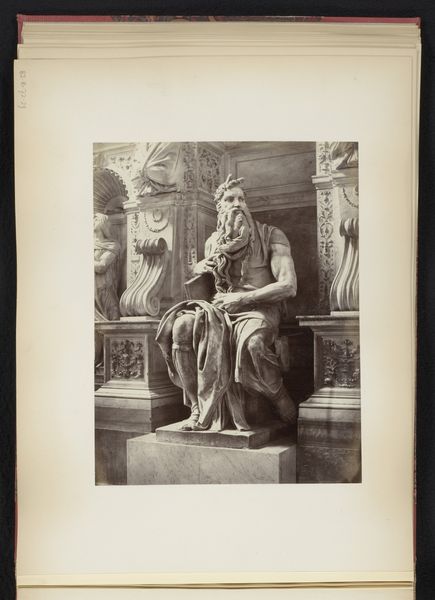

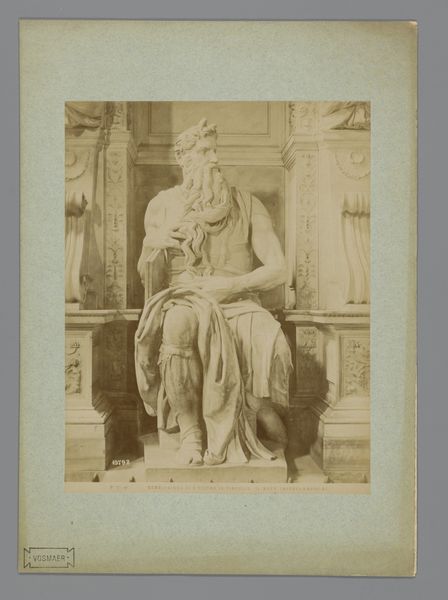

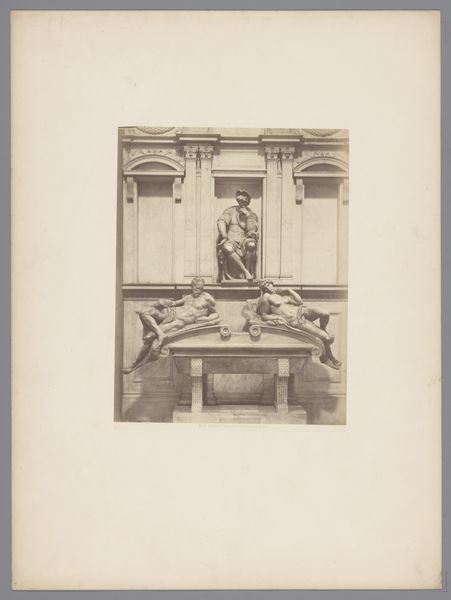

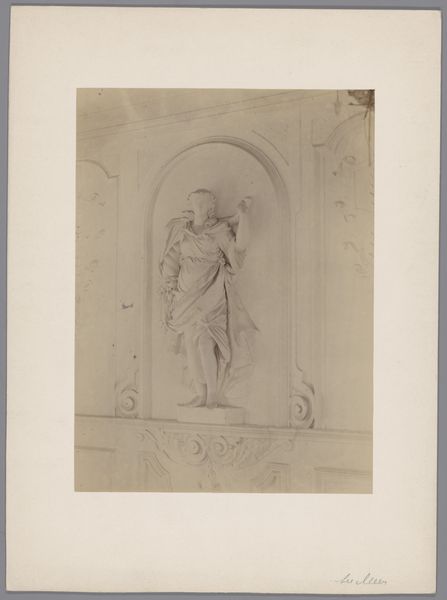

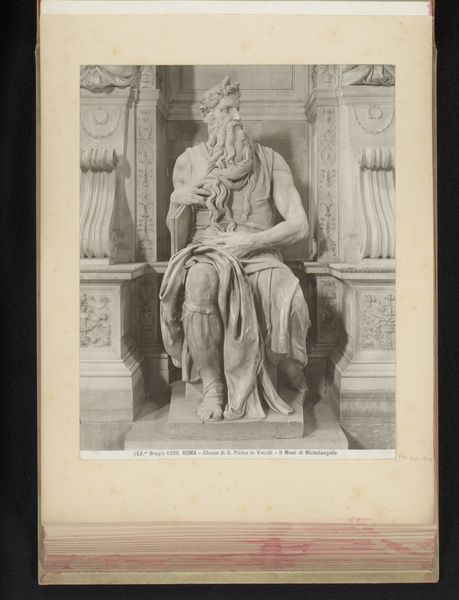

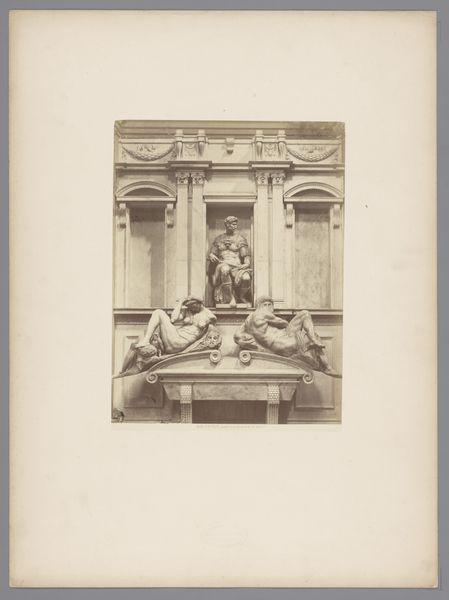

Sculptuur van Mozes in de San Pietro in Vincoli te Rome, Italië 1857 - 1900

0:00

0:00

fratellialinari

Rijksmuseum

photography, sculpture, gelatin-silver-print, marble

#

portrait

#

photography

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

sculpture

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

history-painting

#

marble

#

italian-renaissance

#

realism

Dimensions: height 145 mm, width 100 mm, height 223 mm, width 168 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

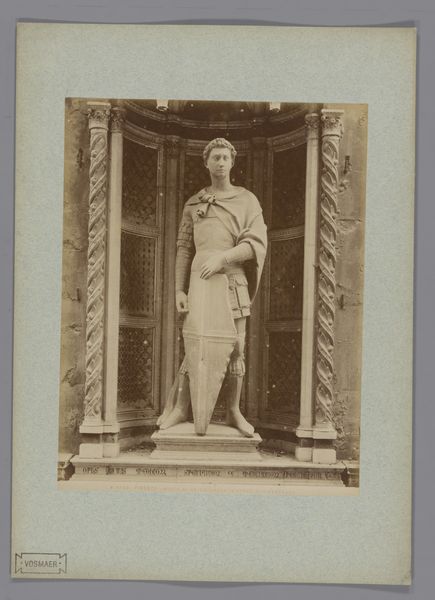

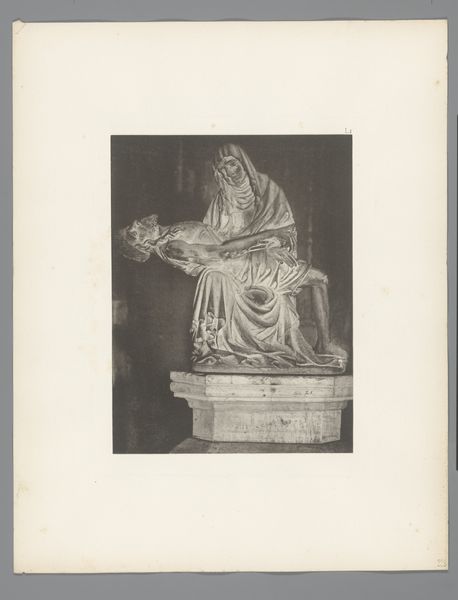

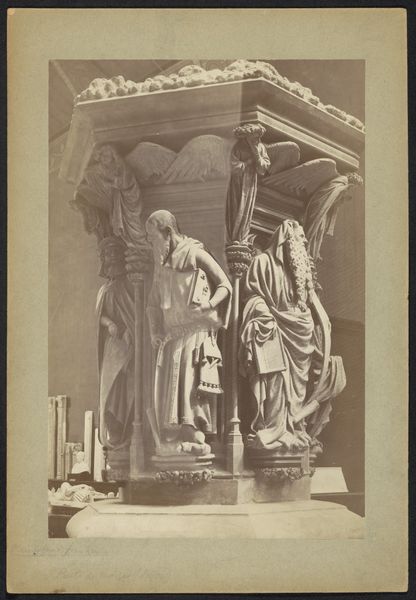

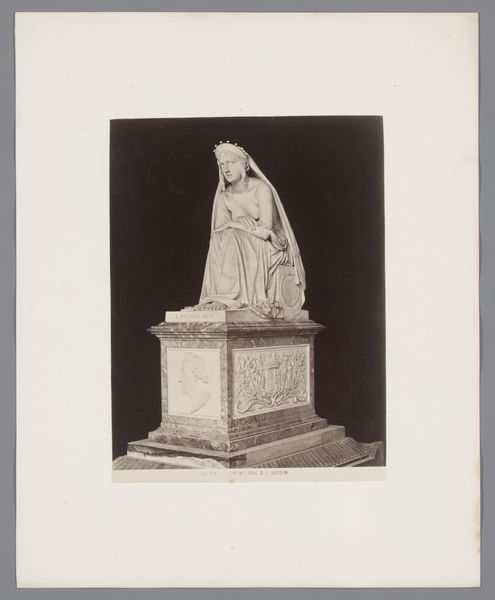

Curator: This gelatin-silver print, taken sometime between 1857 and 1900, captures Michelangelo's Moses sculpture, originally housed in the San Pietro in Vincoli in Rome. The image comes to us courtesy of Fratelli Alinari. Editor: Wow, what a study in stillness! I can almost hear the silence around him, the hushed reverence that such a figure demands. There's such a weight to him, a palpable sense of inner struggle caught in marble. Curator: Precisely! This image speaks volumes about the culture of art reproduction in the late 19th century. Photography enabled wider access to masterpieces, playing a crucial role in disseminating artistic knowledge and shaping public taste. Editor: And democratizing it, to a degree. Imagine seeing Moses only through these kinds of reproductions. Does it dilute the 'aura' Walter Benjamin talks about, or does it amplify the statue’s significance by planting its image everywhere? Curator: That's the crux of it, isn't it? The photograph flattens the original, abstracting the three-dimensional marble into a two-dimensional plane. But simultaneously, it immortalizes it, and transports its essence across time and space. Editor: You know, there’s something almost melancholy about the print's sepia tones, the way the light etches out Moses' form. He seems less a biblical hero here and more a rumination on aging, power, and legacy—seen through a historical filter. Curator: It reflects, in part, how historical narratives shift, or rather get translated to match current preoccupations. In an age of expanding empires, such monumental figures often resonated in specific ways. Editor: It is a bit spooky to see his features looking back at us now through such a timeworn lens. These faded photons still connect us across vast gaps, revealing glimpses of a figure who remains strangely captivating and relevant, no matter how he’s depicted. Curator: Indeed. Photography allowed these sculptures, previously accessible only to certain audiences, to populate public imagination in previously unimaginable ways. Editor: Agreed. In a world increasingly reliant on fleeting images, these lasting testaments remind us that seeing can also be an act of remembering, of grappling with who we were, who we are, and who we hope to become.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.