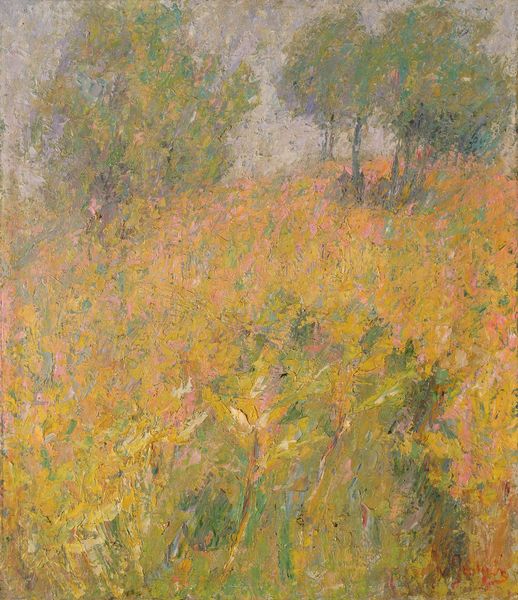

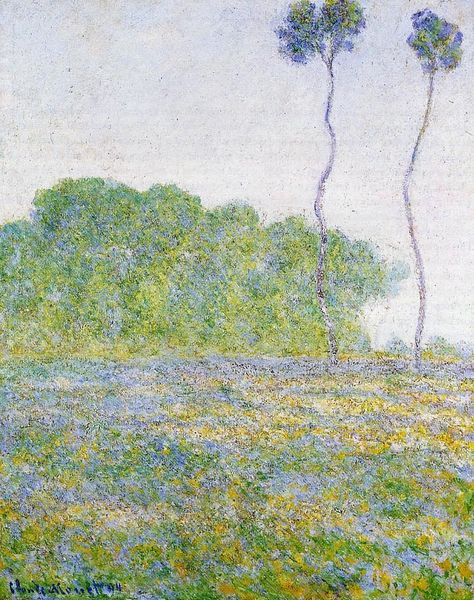

Dimensions: 30 x 45.7 cm

Copyright: Public domain

Curator: Let’s take a look at Charles Sprague Pearce's "Wild Flowers," painted in 1902. It's a lovely example of his plein-air work. What are your first impressions? Editor: Well, it strikes me immediately how tactile it seems. You can almost feel the thick application of the oil paint and the roughness of the canvas. I imagine Pearce was working quickly, capturing the light as it shifted. Curator: Absolutely. Pearce was very much embedded in the Impressionist movement, which celebrated these quick, informal studies directly from nature. He received training in Paris and often displayed in the Salons. We might consider how he adapts these aesthetics, while negotiating American audiences, and tastes for landscape art at this time. Editor: And look at the variety of brushstrokes – long, vertical strokes in the foreground giving way to dabs and dashes of colour as the eye moves further into the field. The painting seems less concerned with precise botanical detail and more about the process of rendering light and colour. I'd love to know where he sourced his paints and brushes from. Curator: It does blur the boundaries between representation and pure abstraction. What is perhaps most compelling is how this canvas captures a moment, rather than a literal place. These meadows represent an increasing cultural preoccupation with idealizing a romantic notion of leisure time within idyllic pastoral settings. Editor: Yes! It hints at broader shifts within material culture and notions of “free” labor. Consider also that each dab of colour is created through labor itself: the paint created by grinders; the brushes stitched and sewn. It really invites us to look closer at what constitutes labour, artistic and otherwise. Curator: A fitting way to end our reflections today. I agree it presents itself as a casual painting but implies complex histories and socio-economic implications that ask more from its viewers. Editor: Indeed. It certainly pushes you to consider the making of a world, and a work of art, simultaneously.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.