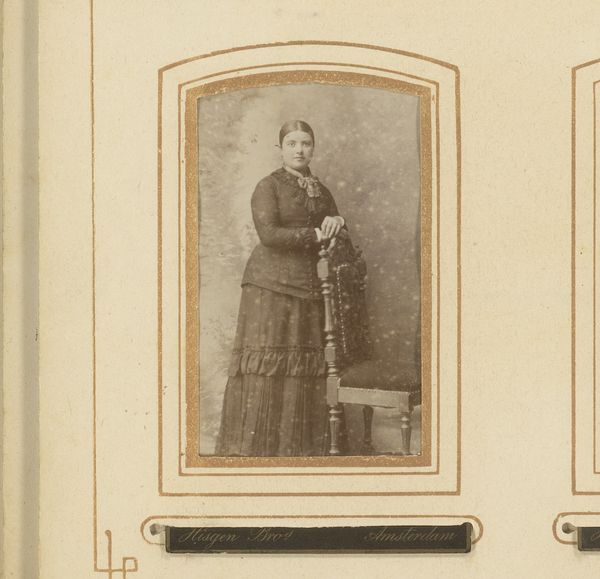

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

19th century

Dimensions: height 85 mm, width 53 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This gelatin silver print, likely from between 1857 and 1898, offers us "Portret van een oude vrouw, zittend aan een tafel," by Pieter Siewers. What strikes you initially? Editor: The woman’s face, surprisingly. It is etched with such a tender and complex understanding of life—that subtle smile almost like a secret between her and time. But also, I can't help but focus on that heavy, dark dress. Curator: You see the weight, the very palpable materiality there, of course! Considering this would have been a somewhat arduous photographic process, it speaks volumes that someone went through all that effort to capture… what, an elder’s quiet dignity? And think about the labor involved in making the dress, sourcing and weaving and all! Editor: Exactly! The dress whispers of wool or some similarly dense fabric—think of the bodies who spun the yarn, wove the cloth, the hours and energy spent sewing. Photography in the 19th century, it's easy to romanticize, but we need to see beyond the quaint portrait and grasp the material circumstances, too. Curator: Well, let’s not entirely forsake the magic of that era. Photography democratized portraiture, remember. Before, this sort of image would’ve been exclusively for the well-to-do; imagine all those untold stories, suddenly finding a visual echo. I wonder who she was, this woman? Did she work in the mills that maybe produced that very dress? Editor: That’s precisely the point, isn't it? It's this convergence of individual story, social fabric, and yes, artistic representation. This image exists as the confluence of countless invisible labor practices and the emergence of new technologies. Curator: It also strikes me that the light softens all those harder edges of history—there’s an undeniable grace, an elegance of spirit in the composition itself. She’s so self-possessed! Editor: And a testament, perhaps, to the power inherent in any single image. We might look at the technical craft, the social conditions, the material origins, but you are drawn to this photograph for the enduring sense of the subject, captured just as she chose to be. Curator: Yes, she transcends the factual… there's an inner world at play in her eyes that no amount of historical contextualizing can diminish. What is recorded on film gives the image a unique texture and makes me want to feel her memories and the sense of history in that era. Editor: True, and it serves as a tangible link. A material connection to a past world – a portrait shaped not only by art, but by the broader processes that define our human condition.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.