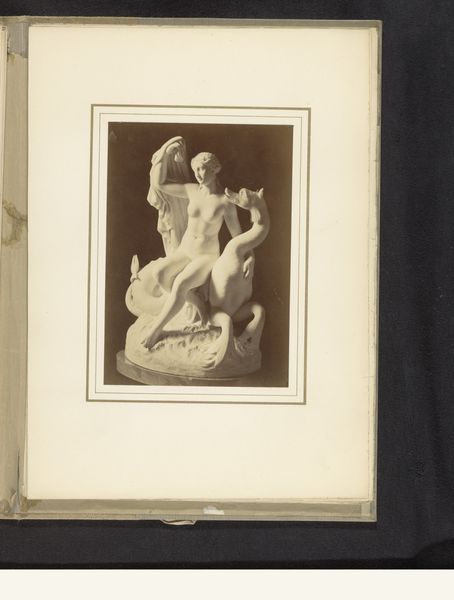

Sculptuur van een vrouw met een leeuw door Guillaume Geefs, tentoongesteld op de Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations van 1851 in Londen 1851

0:00

0:00

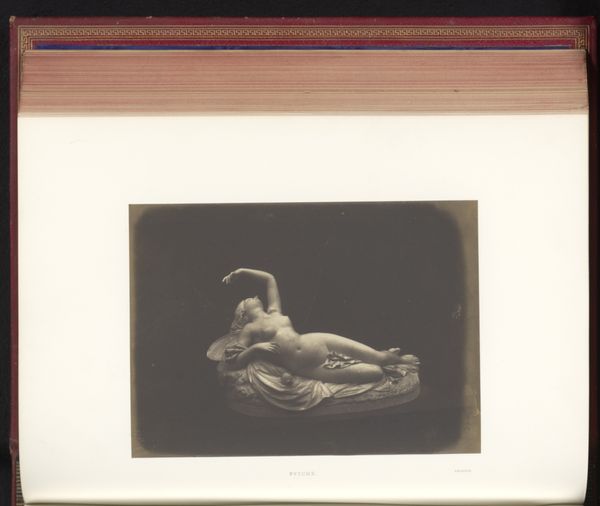

Dimensions: height 177 mm, width 224 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

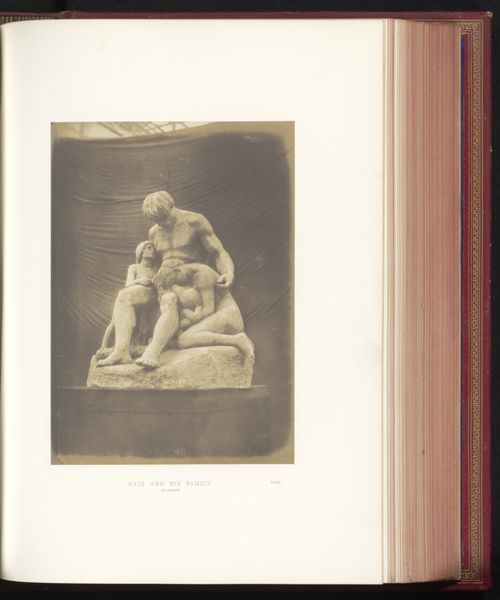

Curator: Immediately, the overwhelming impression is one of contrasting textures—the smooth, polished marble of the woman against the rough, bristling mane of the lion. There's an intense physicality in this juxtaposition. Editor: And physicality was certainly at the forefront in 1851 when Guillaume Geefs exhibited this very sculpture, titled "Sculpture of a woman with a lion," at London’s Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations. The image we see here documents its display at that landmark event. Curator: Its display context explains so much. Considering this was showcased at an exhibition celebrating industry, it is clear that it served less as a portrait, and more as an ideal type or symbol. A powerful female figure sits, calm and self-possessed, seemingly taming a lion with minimal effort. Her hand gently strokes the beast’s face. Editor: Absolutely, and that contrast also speaks volumes about Victorian societal ideals, doesn’t it? The lion, representing raw, untamed nature, is subdued by female virtue, reflecting imperial power exerted with supposed benevolence. These nationalistic aspirations of civilization emerge in sharp detail, right? Curator: Undeniably, the sculptor has emphasized this control through specific compositional choices. Look at how the lion's body forms a horizontal line, creating stability, while the woman's upright posture signifies her dominance. The flowing drapery echoes the mane, softening her powerful stance. Editor: That's right. It becomes clear how the Romantics used classicising styles to comment on the cultural politics and ideals of their day. But also keep in mind the art world’s growing middle class— the market system made public spectacles out of art by celebrating individuality through commissioned works such as this. Curator: I see that interplay clearly in the refined modelling and idealized form of the woman. Her features are smooth, almost generic. The light caresses the marble, lending a cool, almost ethereal glow, typical of Neoclassical influence, but romanticized for added impact. Editor: Indeed. It also prompts considering how it would've functioned in that overwhelmingly spectacular display among other objects. Its meaning was dictated not just by what the sculptor put in, but where the sculpture was placed. I wager most viewers might've glossed over the message altogether while gawking at its immaculate material realism and sheer skill of carving marble. Curator: Ultimately, then, Geefs’s artwork acts as a potent distillation of Victorian power dynamics rendered in a precise, material form. The woman dominates, both physically and symbolically. Editor: And, on the whole, as cultural and aesthetic object, its success stems less from how clearly it makes any claims about female dominance and far more from how it so neatly facilitated imperial fantasies, both on a micro and macro level.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.