drawing, etching, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

#

16_19th-century

#

french

#

etching

#

etching

#

figuration

#

romanesque

#

pencil

#

15_18th-century

#

line

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

Copyright: Public Domain

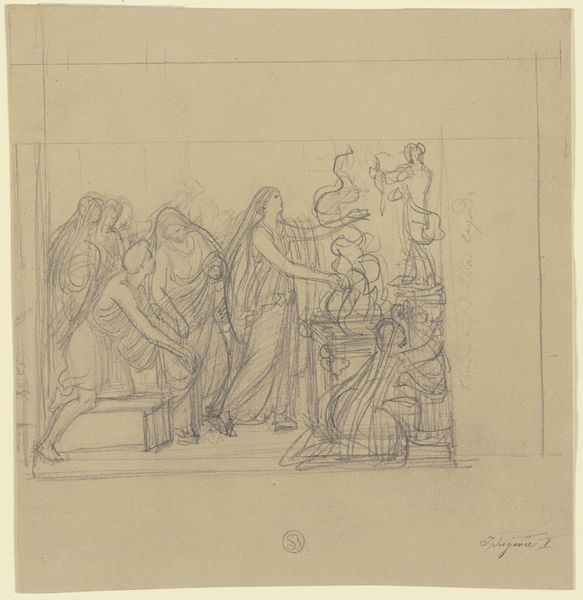

Curator: Charles Johannot created this piece in 1810, titled "Die Liktoren bringen Brutus die Leichname seiner Söhne," or "The Lictors Bring Brutus the Bodies of His Sons." It's currently held in the Städel Museum. Editor: The overriding impression is…sorrow. The figures, though lightly rendered in pencil and etching, communicate a potent grief through their postures. Curator: Absolutely. This historical drawing captures a pivotal moment loaded with political and personal conflict, fitting neatly within the Neoclassical art movement and its obsession with civic duty and morality. Editor: It strikes me how it is still pertinent today. Brutus, positioned to the left, appears isolated, seemingly paralyzed by the sacrifice he made for the Roman Republic by ordering the execution of his own sons for treason. The stark, minimalist composition reinforces this feeling of moral reckoning, highlighting the conflict between patriarchy, justice, and personal devastation. Curator: Contextually, we can look at how Johannot navigates this very charged historical narrative during a time of major shifts in governance. The depiction invites reflections on themes of authority and its impact on family and gender roles of the time. The women, for instance, register strong opposition compared to Brutus' quiet acceptance. Editor: Yes, there's a visible imbalance there. The artist's choice to emphasize their anguish opens up considerations of the psychological and social toll exacted on those left behind. What did Roman womanhood represent when measured against state imperatives? Curator: I would like to mention Johannot's academic art training is very clear through his refined linear technique and compositional organization. The artist also uses the space creatively; in the architectural forms you sense a classicizing aspiration that echoes broader societal efforts toward stability and order following turbulent periods of revolution. Editor: Seeing the faces lined with despair, I now feel overwhelmed by how historical records often highlight just political ideals without regard for individuals trapped in them. A society only functions well, if, regardless of sacrifice, individual experience counts. Curator: Indeed. It allows us a window onto these past events. Looking back from our contemporary perspectives we may start to ask more relevant questions concerning those experiences, thereby enriching our engagement with historical pieces such as these. Editor: So very true. The interplay of grief, state duty, gender and moral compromise make it far more than just historical narrative, rather an active critical intervention from within and a lens through which to think about power today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.