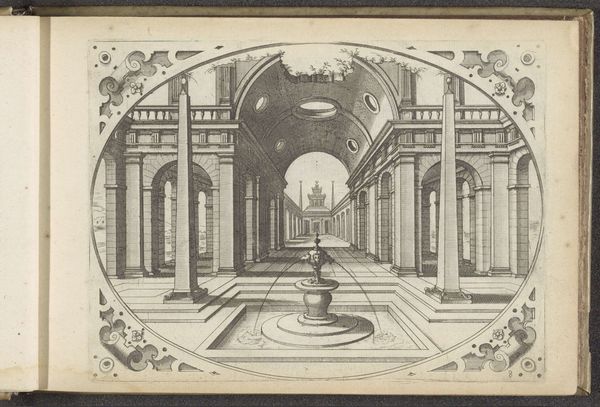

Open colonnade met zuilen en kruisgewelven boven een vijver 1560 - 1601

0:00

0:00

johannesoflucasvandoetechum

Rijksmuseum

Dimensions: height 163 mm, width 214 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: What strikes me first is the almost unsettling precision. The artist’s meticulous use of line emphasizes a constructed, deliberate artificiality. Editor: This engraving by Johannes or Lucas van Doetechum, created between 1560 and 1601, is titled "Open colonnade met zuilen en kruisgewelven boven een vijver"—or, in English, "Open colonnade with columns and cross vaults above a pond." Curator: It's all lines! The labor that goes into creating such architectural details – each pillar, each ripple in the water – through mere engraved lines. What would it be like to actually construct the scene as shown here? The time, the planning, the exploitation of the workers! Editor: You bring up a crucial point about labor. These architectural prints were not simply aesthetic objects. They circulated designs, knowledge, and aspiration, but for whom? Certainly, it speaks to a very specific aristocratic or merchant class with both the power and leisure for patronage and property development. Note how perspective itself, with its vanishing point in this central structure, emphasizes the viewer's position of control. Curator: Indeed. The scale too! Everything seems meant to dominate, doesn't it? What about the role of the printing press in democratizing architectural ideas, or does it simply end up serving elite interests and reinforcing those divisions? This makes me think about the economics of artistic labor. Editor: That's a critical tension. Was it a force for democratization or further entrenchment of existing power structures? This image makes me think of Alberti’s theories—using art to showcase power—particularly how spaces themselves control human interaction, constructing gender and class. This structure isolates as much as it incorporates. Who is really welcome to such spaces? The lack of visible people makes it even more obvious. Curator: The materiality of the print itself becomes a point of inquiry – paper, ink, the press. Its purpose, both artistic and functional, embodies tensions between manual labor, intellectual design, class, and industry. Editor: Agreed. Understanding art requires understanding not only aesthetics but social, and material realities behind its creation. What you point out regarding the labor contrasts against the image which shows a tranquil location for elites, revealing the work needed to create such fantasies. Curator: Ultimately, this exercise reveals a paradox: Art and function, the beautiful and useful, only emerge as results of specific circumstances. Editor: Right. That's precisely why viewing these historical prints within broader societal narratives proves so crucial to truly understand the art we engage with.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.