drawing, dry-media

#

drawing

#

pencil sketch

#

charcoal drawing

#

figuration

#

form

#

dry-media

#

pencil drawing

#

line

#

academic-art

#

nude

#

rococo

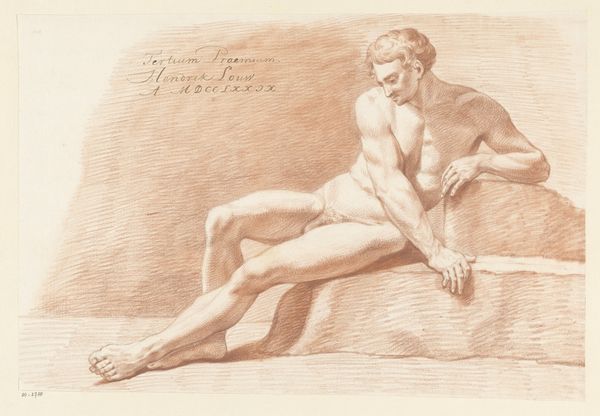

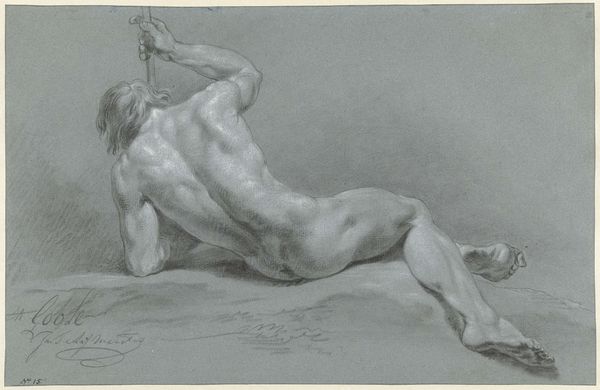

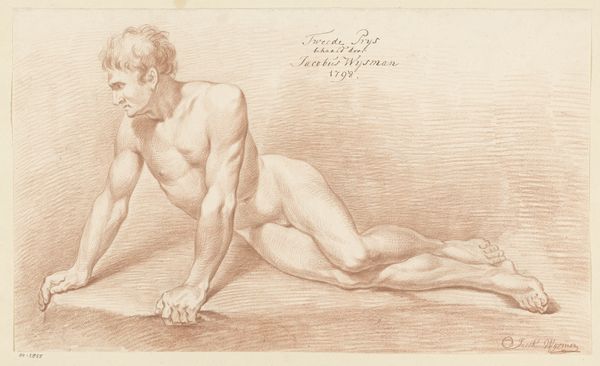

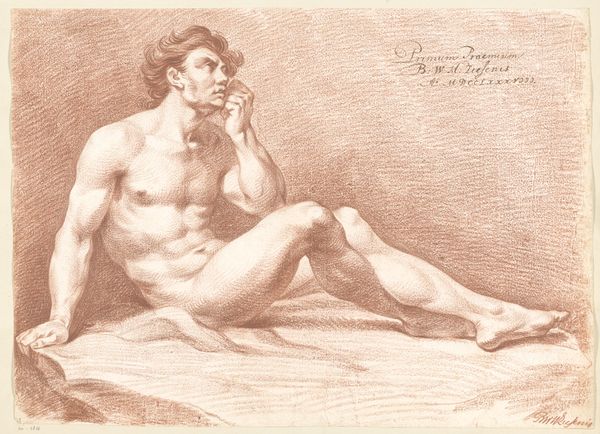

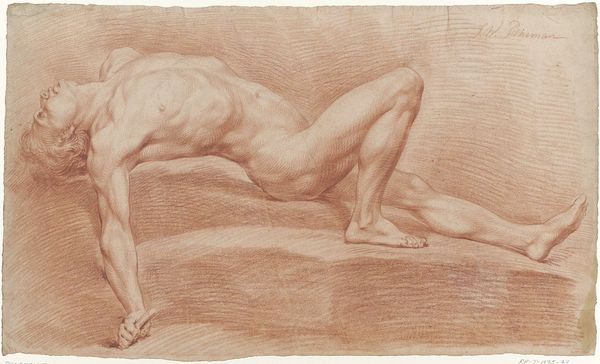

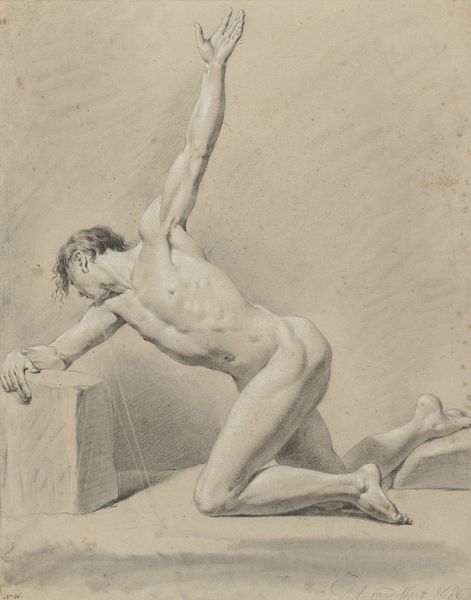

Dimensions: height 522 mm, width 389 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: What strikes me immediately is the posture—one of almost languid defeat. There’s a vulnerability in that raised arm exposing the torso. Editor: Indeed. This is “Liggend mannelijke naakt,” or "Reclining Male Nude," a drawing by Gilles Demarteau, likely created between 1732 and 1776. The work is a dry-media drawing, using techniques such as pencil and charcoal to bring this form to life. Demarteau was deeply embedded in the artistic milieu of 18th-century France, where academic art heavily influenced the training and practices of artists. Curator: So, within the context of academic training, was this kind of study—the male nude—almost a standardized exercise, a way to learn the canon? Did it play a particular role in shaping masculine ideals in art, beyond just anatomical study? Editor: Absolutely. The male nude was central to the artistic discourse, embodying ideals of beauty, strength, and virtue, albeit within a patriarchal framework that often privileged the male gaze. Its reproduction in academic circles was both a training tool and a means of reinforcing certain societal standards of beauty and the perceived superiority of the male form. Curator: Considering that context, it makes me think about how gender roles are policed through art—even studies like this one. Is the pose meant to signify vulnerability, or perhaps something else? Is there an interplay between that classical, almost heroic physique, and the gesture of self-exposure? The hand covering where the head should be almost implies anonymity. Editor: It’s fascinating how you bring in those contemporary considerations. I see it fitting within the rococo era— the lines and forms speak to it—as a negotiation of established forms of representation. Rococo tended towards elaborate ornamentation, softness, and a rejection of strict classicism. Demarteau has found a midpoint: this isn't a celebratory depiction, it's in progress and pensive, perhaps alluding to an emerging sensitivity to art's purpose during times of societal shifts. Curator: That makes perfect sense. Perhaps by detaching the figure from a heroic narrative and softening those traditional power structures, we can see Demarteau's art contributing to broader re-evaluations of gender and power dynamics. Editor: Ultimately, the drawing serves not only as a study in form but also as a fascinating document of evolving cultural ideals and the ways in which artistic representation can reflect and shape these changes. Curator: Precisely—it makes us ponder how we project current values onto art from the past, offering pathways to interrogate our perspectives now.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.